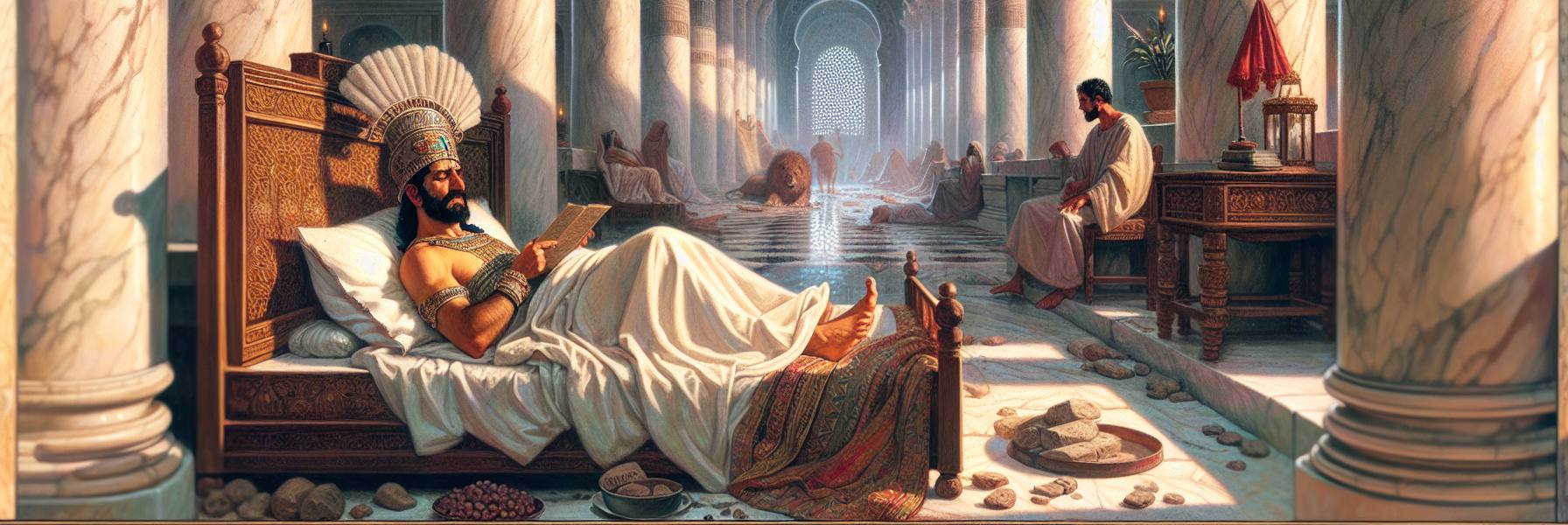

The night was the kind that clung to the skin, hot and airless even within the marble halls of Susa’s citadel. King Ahasuerus, a man accustomed to every comfort, found no solace in his silken sheets. Sleep was a fugitive. He tossed, the weight of the empire—the reports from Egypt, the grain levies from Babylon, the endless, whispering intrigues of the court—a tangible pressure on his chest. Finally, with a grunt of frustration, he rose. A servant, dozing by the door, startled into alertness.

“The chronicles,” the king said, his voice rough with weariness. “Bring the records of my reign. The annals. Perhaps the dry prose of my scribes will bore me into oblivion.”

The servant scurried off, returning with a clay tablet and a series of leather scrolls. The king dismissed him, preferring the lonely company of his own history. The lamplight flickered, casting dancing shadows on the bas-reliefs of lions and conquests that adorned his chamber. He unrolled a scroll, his eyes skimming accounts of tributaries and treaties. Then, his finger paused on a passage.

It detailed an event from years prior—two of his own chamberlains, Bigthana and Teresh, guards of the threshold, who had grown bitter and conspired to lay hands on the king. The writing was stark, bureaucratic. But the next line mentioned, almost as an aside, the man who had uncovered the plot: Mordecai, a Judahite from the citadel’s gate, who had sent word through Esther the queen. Ahasuerus frowned, memory stirring. He remembered the execution of the traitors, the swift, brutal justice. But he could not recall any reward being given to the informant.

“What honour or dignity,” he murmured to the silent room, “was bestowed upon Mordecai for this?”

The question hung in the stifling air. It felt like an administrative oversight, a debt unpaid. At that moment, as if summoned by the king’s restless conscience, a sound came from the outer court—the soft, shuffling tread of someone approaching. Dawn was still a grey suggestion in the east.

“Who is in the court?” Ahasuerus called out.

A guard’s voice answered, “It is Haman, Your Majesty, standing in the outer court.”

Haman. The Agagite, the man he had recently elevated, the one to whom he had given his royal signet ring. Ahasuerus felt a minor surge of relief. Here was his most trusted advisor, arriving before the sun, surely a man of diligence. “Let him enter,” the king said.

Haman swept in, his robes immaculate, his bearing one of coiled anticipation. He had come for one purpose only: to secure the king’s consent to hang Mordecai on the gallows he had spent the evening constructing—a towering structure of timber in his own courtyard, a private monument to his hatred. The thought of it had sweetened his wine the night before.

Before Haman could utter a word, the king posed his question. “What should be done for the man the king delights to honour?”

Haman’s heart, so full of its own dark purpose, leapt. *The king delights to honour?* His mind raced. Whom could he possibly delight to honour more than me? There is no one. The question was a mirror, and in it Haman saw only his own magnificent reflection.

He drew himself up, a smile playing on his lips. “For the man the king delights to honour,” Haman began, his voice taking on a ceremonial cadence, “let them bring a royal robe that the king himself has worn, and a horse that the king has ridden, one with a royal crest upon its head. Then let the robe and the horse be entrusted to one of the king’s most noble officials. Let him array the man whom the king delights to honour, and lead him on horseback through the open square of the city, proclaiming before him: ‘Thus shall it be done to the man whom the king delights to honour!’”

It was a perfect tableau, every detail plucked from Haman’s own vanity—the intimacy of the king’s own garments and steed, the public parade, the declaration ringing through the streets. He imagined the weight of that robe on his own shoulders, the feel of the royal reins in his hands.

Ahasuerus, weary but satisfied, nodded. “Excellent. Go quickly,” he commanded, a note of energy entering his voice for the first time that night. “Take the robe and the horse, just as you have said, and do so to Mordecai the Judahite, who sits at the king’s gate. See that you omit nothing of all that you have proposed.”

The words struck Haman like a physical blow. For a moment, the world inverted. The rich tapestries on the walls seemed to sway. *Mordecai? The Judahite? The man in sackcloth?* The name was a curse in his mind. The splendour he had woven for himself was now a shroud to be draped upon his enemy. The gallows, waiting in his courtyard, seemed to mock him from a distance.

He could not speak. He bowed, a stiff, mechanical motion, and backed out of the king’s presence. In the antechamber, the cool dawn air felt like a judgement. He gathered the items—the deep blue, purple, and white robe that smelled faintly of the king’s spices, the great white horse with its headpiece of gold—with hands that felt numb.

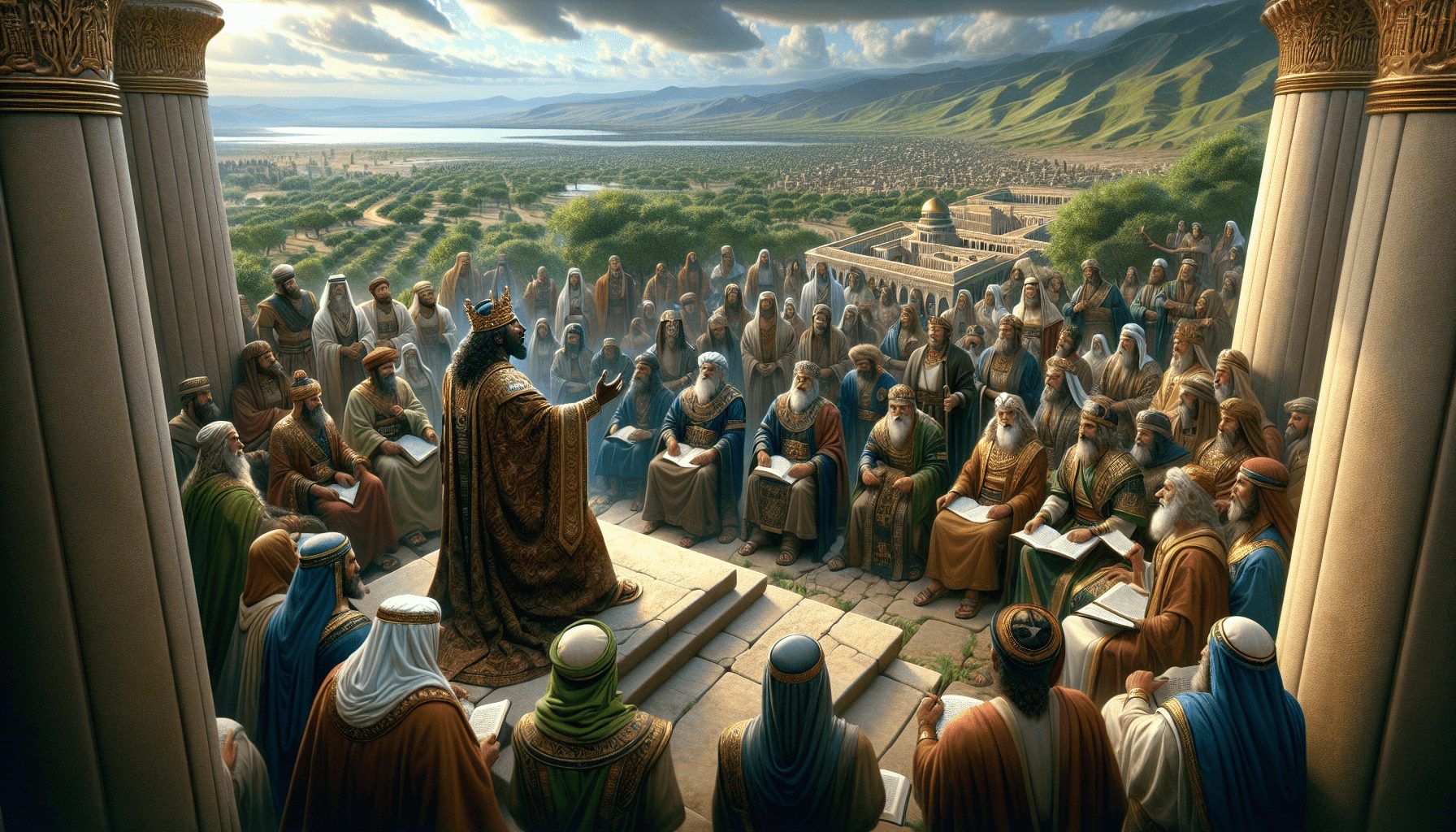

The square of Susa was stirring to life as Haman, his face a mask of mortification, found Mordecai at the gate. Mordecai looked up from his post, his expression inscrutable. He had spent days fasting, clothed in sackcloth and ashes, mourning the edict of death Haman had written. He said nothing as Haman, the king’s most noble prince, dressed him in the king’s own robe, his fingers fumbling with the fastenings. He said nothing as he was helped onto the king’s own horse. He simply sat, erect and quiet, as Haman took the bridle.

Through the broad, stone-paved streets Haman led the horse, his voice, when he forced it out, ringing hollow against the walls: “Thus shall it be done to the man whom the king delights to honour!” Merchants paused, their wares forgotten. Water-carriers set their jars down. Children pointed. The spectacle was utterly bewildering: the hated Agagite, the grand vizier, proclaiming the glory of the solemn Judahite in royal vestments.

When the humiliating parade was finished, Mordecai returned to the king’s gate. He took off the royal robe, folded it, and resumed his place. He was the same man, yet everything was different. Haman, meanwhile, fled the scene. He rushed home, his head covered in a gesture of profound grief and shame, a stark contrast to the pomp he had just enacted.

He called for his wife Zeresh and all his friends. He told them everything—the king’s question, his own proud suggestion, the cruel twist of fate that had named Mordecai as the recipient. The confidence they had shown the day before was gone. Zeresh’s voice was heavy with a superstitious dread. “If Mordecai, before whom you have begun to fall, is of the seed of the Jews,” she said, “you will not overcome him. You will surely fall before him.”

Their words were still hanging in the hushed, opulent room when the king’s eunuchs arrived. They had come to escort Haman to the second banquet Esther had prepared. The summons felt less like an honour now and more like a sentence. The sun was higher now, the day fully born, and it illuminated a world where every certainty Haman possessed had crumbled to dust. He went, his feet heavy, the memory of Mordecai seated on the king’s horse burning behind his eyes, a silent, triumphant prophecy riding in his wake.