The heat in Jerusalem was a physical thing that summer. It lay upon the city like a woolen blanket soaked in brine, heavy and suffocating. The dust from the southern road, however, was a different kind of affliction. It arrived not with the wind, but in plumes kicked up by the endless traffic of chariots, messengers, and supply trains. It coated the leaves of the olive trees in the Kidron Valley with a fine, pale powder. It gritted between the teeth of the merchants in the upper city, and it settled in the folds of the robes of the elders who clustered in the shadowed alcoves of the palace, their voices low and urgent.

Eliab, a scribe in the court of Hezekiah, felt the dust in his scrolls. He felt it more acutely, perhaps, than the fear. The fear was a constant, familiar hum—the news from the north was a litany of fallen cities: Samaria was a memory, and the Assyrian, a great grinding machine of iron and empire, was turning its terrible, leisurely gaze toward Judah. The fear was in the king’s knotted brow, in the way the military advisors’ fingers tapped on the maps of the Sinai.

But the dust was new. It was the dust of Egypt.

From his small chamber near the archives, Eliab could hear the comings and goings. The delegation had returned from Memphis two days prior, and since then, the palace had thrummed with a nervous, giddy energy. Words like “chariots” and “horsemen” and “a great host” slipped through corridors. The treaty was sealed. Pharaoh’s promise was as solid as the gold that had accompanied the envoys back—a down payment on salvation.

Eliab was tasked with copying the official communiqué for the temple records. The papyrus was of the finest Egyptian stock, smooth and golden. The ink was black and sure. “In the might of Pharaoh Taharqa, our brother and protector, we shall find a strong shield…” he wrote, his stylus moving with a trained, unthinking rhythm. But his mind was elsewhere. It was on the words of the prophet, Isaiah, who had stood in the very court the week before, his frame looking almost frail against the marble pillars, his voice nonetheless filling the space like a trumpet with a cracked note.

“Woe to those who go down to Egypt for help,” the man had said, his eyes not on the king, but on some distant, invisible point, as if reading from a scroll only he could see. “Who rely on horses, who trust in chariots because they are many and in horsemen because they are very strong, but do not look to the Holy One of Israel or consult the Lord.” The silence afterward had been profound, broken only by the dismissive clearing of a counselor’s throat.

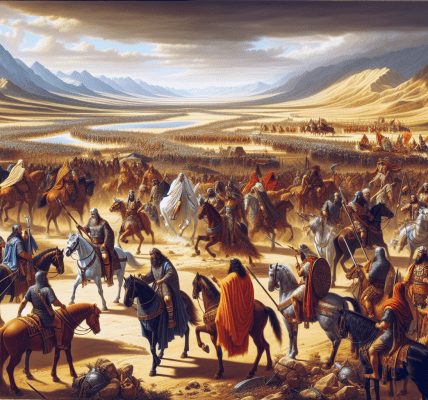

Now, Eliab finished his copy and sanded the ink. He walked out into the blinding courtyard. Near the stables, a new contingent of Egyptian cavalry officers were inspecting Judahite mounts. The horses were magnificent—powerful, sleek animals from the Nile Delta, their muscles rippling under coats the color of dark wine. The officers moved with a confident swagger, their linen garments bright white against the dun-colored stone. One of them laughed, a sharp, foreign sound. They trusted in chariots because they are many.

A memory surfaced, unbidden: his grandfather, a veteran of the old wars, sitting by the fire. “The strength of a man,” the old man had wheezed, “even a thousand men, is like a reed in the river when the mountain decides to move.” He’d been talking about faith, about Zion. Eliab had thought him senile.

That evening, unable to bear the stifling, optimistic air of the palace, he walked the city walls. The watchmen were alert, their eyes scanning the northern hills. From this height, he could see the campfires of the Egyptian expeditionary force twinkling in the valley of Rephaim, a constellation of false security. Jerusalem sat like a crown on her hills, but he felt her fragility. She was trusting in a shadow.

The prophet’s words returned, complete this time: “The Egyptians are man, and not God; and their horses are flesh, and not spirit. When the Lord stretches out his hand, the helper will stumble, and he who is helped will fall, and they will all perish together.”

It was not a political forecast. It was a statement of reality, as fundamental as the law of gravity. Egypt was *flesh*. It would tire, it would break, it would rot. Assyria, for all its terror, was also flesh. But the Lord… He was the fire that dwelt in Zion, the furnace of Jerusalem. Not a symbol. Not a concept. A consuming, actual presence that the temple ritual hinted at but could not contain. This was Isaiah’s maddening, terrifying point: the only real thing in this whole desperate drama was the Holy One, whom they were politely ignoring in favor of something they could count and bargain with.

Days bled into weeks. The Assyrian wolf, Sennacherib, drew nearer. Lachish fell, and the stories of its horrors seeped into the city like a stain. The Egyptian alliance was now the sole topic of every conversation, the sole plank in a raft above a raging sea. The chariots were counted again. The horsemen were drilled. The gold was spent.

Then the news came, not from the north, but from the south. The Egyptian army, Judah’s great hope, had marched to intercept the Assyrians. They met at Eltekeh. And there, the great host of Pharaoh, the innumerable chariots, the invincible horsemen—they stumbled. They did not break in a heroic last stand; reports spoke of confusion, a failure of flank, a strategic withdrawal that looked to every observer like a rout. The helper stumbled.

Panic, cold and pure, finally replaced the anxious hope in Jerusalem. The raft was gone. They were in the water.

Eliab stood again on the wall as the first Assyrian advance scouts were sighted, dark specks on the northern ridge. The Egyptian camp in the valley was a scene of frantic, disorganized packing. The dust they kicked up now was not the dust of promise, but the dust of retreat. He thought of the words he had so carefully copied, the golden papyrus now as worthless as last year’s leaves. He looked inward, toward the temple mount, where the smoke of the evening sacrifice still coiled into the twilight sky.

A strange quiet settled over him. It was the quiet after a bone snaps, when the pain hasn’t yet arrived, only the shocking, clean truth of the break. All the clever plans, the treaties written on fine papyrus, the magnificent horses—flesh, all flesh. They had sought a helper made of the same crumbling clay as their enemy.

But the fire in Zion still burned. The furnace of Jerusalem was not a metaphor for their own martial spirit. It was *Him*. And His hand was now stretched out—not yet against the Assyrian, but against every pillar of false trust they had built. The falling was necessary. The perishing of their hopes was the prerequisite.

As the first true night of the siege descended, Eliab did not go to the archives. He went to his home, gathered his family, and they did what felt, in that moment, like the only real action left. They prayed. Not to a concept of deliverance, not for the return of the Egyptians, but to the Holy One, the fire, whose will was the only solid ground in a world of sinking sand. The helper had fallen. Now, they would see if the Lord would pass over them, or come down to fight. And for the first time that long, hot summer, Eliab felt he was dealing with something real.