The air in the camp was thick with more than just the fine, chalky dust of the desert. It was heavy with a new kind of heat, a simmering resentment that had been brewing in the shadows of the tents, fed by whispers and sidelong glances. Korah, a Levite of some standing, felt the weight of his lineage like a chain. He was of the tribe of Levi, set apart for the service of the Tabernacle, yet he watched Moses and Aaron, these two old men, stand as if they were closer to the cloud of God’s presence than any other.

He gathered others to him, a council of discontent in the dim light of his tent. Dathan and Abiram, sons of Reuben, their faces hard with the memory of a promised land they had not seen. Two hundred and fifty men of renown, leaders of the congregation, princes. Their pride was a tangible thing in the close air.

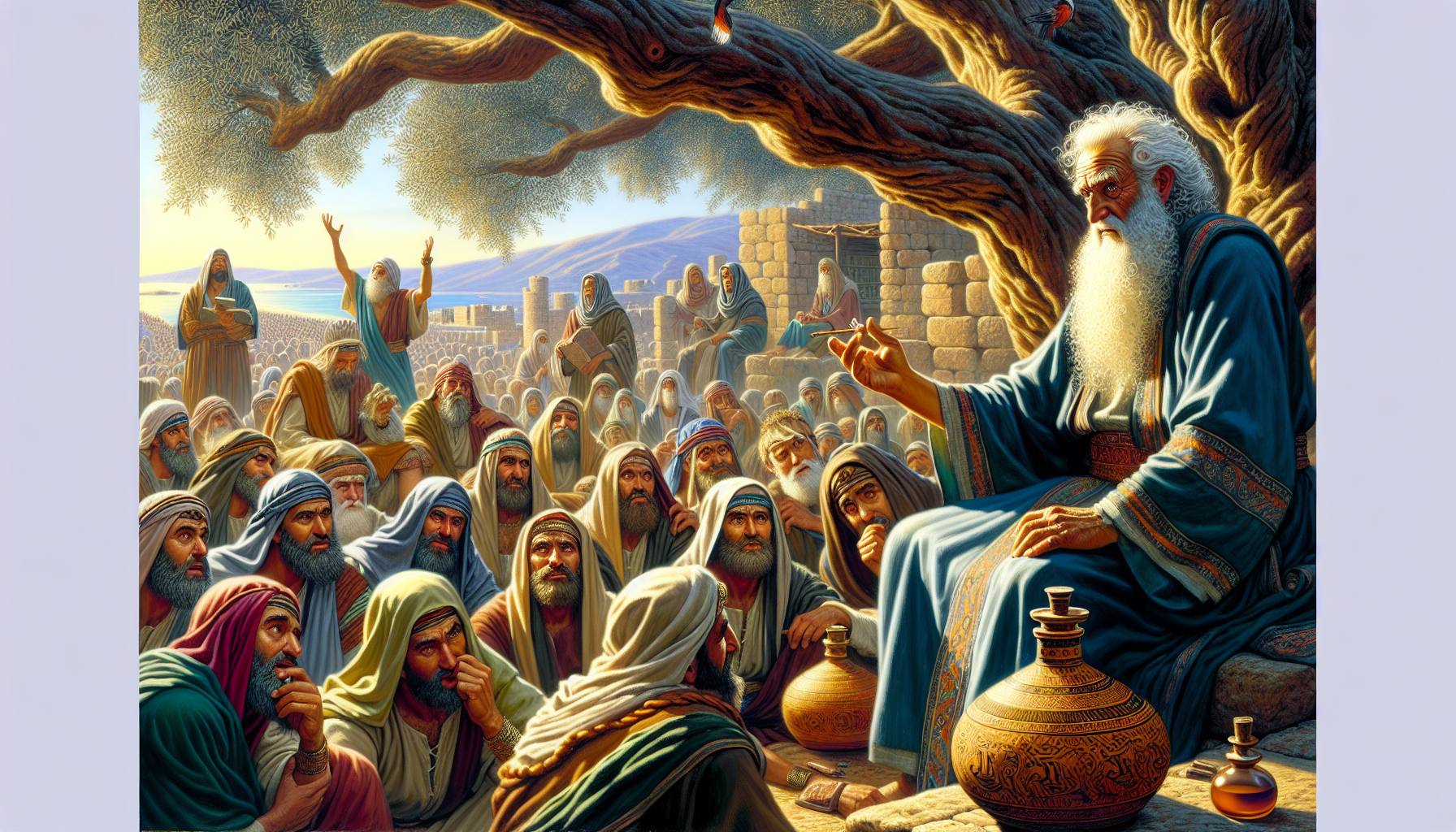

“You take too much upon yourselves,” Korah said to Moses and Aaron the next morning, his voice carrying across the open space before the Tabernacle. The sun was harsh, bleaching the color from everything. “The whole congregation is holy, every one of them, and the Lord is among them. Why then do you exalt yourselves above the assembly of the Lord?”

Moses heard the words, but he felt the spirit behind them—a cold, sharp blade of ambition disguised as piety. The weariness that was his constant companion these forty years settled deeper into his bones. He did not respond with anger, but with a profound, grieving stillness. He fell on his face. It was his habitual posture before God, a recognition of his own utter dependence.

When he rose, his voice was low, but it carried. “Listen now, you sons of Levi,” he said. “Is it a small thing to you that the God of Israel has separated you from the congregation of Israel, to bring you near to Himself, to do the service of the Tabernacle of the Lord, and to stand before the congregation to minister to them? He has brought you near, and all your brethren the sons of Levi with you. And do you seek the priesthood also? Therefore, you and all your company are gathered together against the Lord. And what is Aaron, that you murmur against him?”

He proposed a test, a terrible and direct appeal to the divine. “Tomorrow, take censers, you Korah and all your company. Put fire in them and put incense on them before the Lord. And the man whom the Lord chooses, he shall be holy. You take too much upon yourselves, you sons of Levi.”

The next day arrived with a tense, unnatural quiet. The community had gathered at the entrance of the Tabernacle, a sea of anxious faces. Korah and his two hundred and fifty accomplices stood with their bronze censers, the fire within them flickering, the sweet, heavy scent of incense beginning to weave through the air, a fragrance of usurped worship.

Then the glory of the Lord appeared to all the congregation, a palpable pressure, a light that was not of the sun, and a silence that swallowed all other sound.

The Lord spoke to Moses and Aaron, his voice a thought formed in their minds, a command that chilled them. “Separate yourselves from among this congregation, that I may consume them in a moment.”

But again, Moses and Aaron fell on their faces. Their plea was not for themselves, but for the people. “O God, the God of the spirits of all flesh,” Moses cried out, his voice cracking, “shall one man sin, and will You be angry with all the congregation?”

The instruction was given. A judgment of terrifying specificity. “Speak to the congregation,” the voice said, “and get away from the tents of Korah, Dathan, and Abiram.”

Moses, his legs feeling like stone, went to the tents of Dathan and Abiram. The elders of Israel followed at a distance, a grim procession. He did not enter their camp, but stood at its edge and called out, his voice carrying over the low tents. “Depart, please, from the tents of these wicked men, and touch nothing of theirs, lest you be consumed in all their sins.”

A hush fell. Then, a slow, deliberate movement began as the people backed away from the tents of the rebels, creating a wide, empty circle of trampled earth around them. Dathan and Abiram came out and stood at the doors of their tents, their wives and their sons and their little children with them, a final, defiant posture.

Moses stood alone in the cleared space, an old man facing the families of his accusers. His voice was clear and carried a terrible finality. “By this you shall know that the Lord has sent me to do all these works, for I have not done them of my own mind. If these men die as all men die, or if they are visited by the common fate of all men, then the Lord has not sent me. But if the Lord creates a new thing, and the ground opens its mouth and swallows them up, with all that belongs to them, and they go down alive into Sheol, then you shall understand that these men have despised the Lord.”

The moment he finished speaking, the ground beneath their feet groaned. It was a deep, subterranean sound that vibrated up through the soles of their sandals. Then the earth itself split apart with a roar. The rift was not a clean crack, but a ragged, hungry maw that opened directly beneath the tents of Korah, Dathan, and Abiram. The ground gave way, a collapsing sinkhole of sand and rock. There was a single, unified cry of terror, cut short as the earth closed over them. They and all that belonged to them—their tents, their possessions, their families—were gone, swallowed whole into the darkness beneath. The ground sealed itself, leaving only a raw, scarred patch of earth. A profound silence returned, broken only by the panicked shrieks of the people as they fled from the place, fearing the earth would consume them, too.

Then fire flashed out from the presence of the Lord, a swift, divine lightning. It fell among the two hundred and fifty men who were offering the incense, and they were consumed. Their bodies fell where they stood, their bronze censers clattering to the ground, now just so much metal, holy objects profaned by unholy hands.

The aftermath was a scene of stunned horror. The people murmured, not in rebellion now, but in fear. “The earth has swallowed them! We will all be consumed!” The next day, the grumbling began again, this time directed at Moses and Aaron. “You have killed the people of the Lord,” they accused.

As the congregation assembled against them, Moses and Aaron turned toward the Tabernacle. And behold, the cloud covered it, and the glory of the Lord appeared. Moses went inside to speak, and the Lord’s instruction was swift. “Get away from among this congregation, that I may consume them in a moment.”

A plague had already begun its work. People were falling where they stood, their bodies stricken. Moses, in a frantic act of intercession, shouted to Aaron. “Take a censer! Put fire in it from the altar! Put on incense! Go quickly to the congregation and make atonement for them!”

Aaron did not hesitate. He ran, the priestly bells on his robe jangling a frantic rhythm, the censer swinging, smoke trailing behind him. He placed himself between the dead and the living, standing in the breach as the plague raged through the camp. He offered the incense, the smoke a plea for mercy rising to heaven. And the plague stopped. But the cost was counted: fourteen thousand seven hundred dead, besides those who had died in the matter of Korah.

To provide a final, enduring sign, the Lord commanded Moses. “Tell Eleazar, the son of Aaron the priest, to take up the censers out of the blaze, for they are holy. And let them be hammered out as a covering for the altar.”

So the bronze from the censers of the men who had sinned at the cost of their lives was hammered into a thin sheet and placed as a covering over the altar. It was to be a sign, a permanent memorial to the children of Israel, that no one who is not a descendant of Aaron should come near to offer incense before the Lord, lest he become like Korah and his company. The altar itself now bore the metallic skin of their rebellion, a silent, gleaming warning for all who approached to worship.