The memory of the Bashan campaign comes to me not as a single event, but as a smear of dust, smoke, and the deep, unsettling quiet that follows a great noise. We had turned north, away from the arid south, and the land itself seemed to change its character. It was a country of giants, or so the reports said, and the reports weren’t wrong. Og, king of Bashan, his very name a guttural threat, came out against us at Edrei.

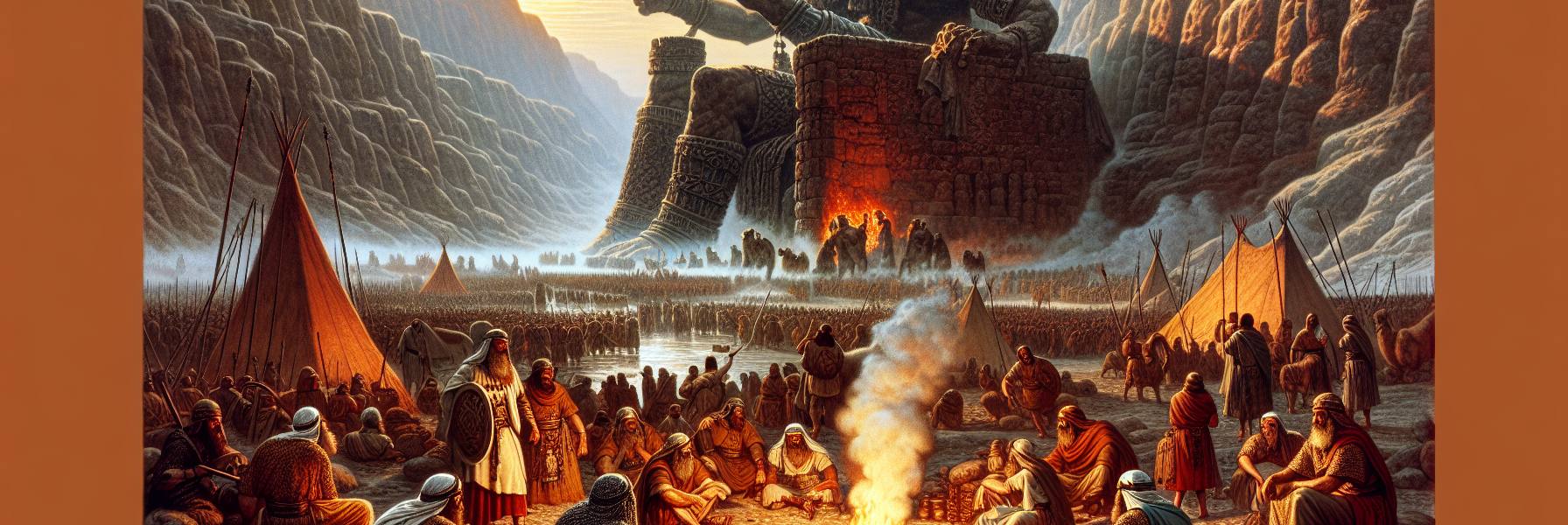

I remember the council fire the night before. The flames danced in the eyes of the men, young and old. There was a different kind of fear here, not of hunger or thirst, but of legend. “His bed is iron,” someone whispered, “nine cubits long and four wide. It sits in Rabbah still.” The measurement hung in the air. A bed for a creature, not a man. Joshua, solid and quiet beside me, just stared into the fire, his jaw set. I heard the Lord’s voice then, a certainty in my spirit that cut through the campfire talk. “Do not fear him,” it was not a shout, but a foundation laid beneath my feet. “For I have given him into your hand, and all his people and his land.”

The battle itself is a confusion in my mind—the strange, thick oak forests of Bashan, the way our lines advanced through clearings where the light fell in heavy shafts. They had fortified cities, high walls with gates that seemed to swallow the landscape, places like Ashtaroth and Edrei. But there was a brittleness to them. Their strength was in stone and reputation, not in the spirit that held them. When the lines met, it was less a clash and more a breaking. The Lord delivered Og into our hands completely. We left no survivor. It sounds harsh, said plainly like that. Out there, in the grit and the screaming, it was a terrible necessity, a surgery to remove a sickness from the land. We took all his cities, sixty of them, a whole fortified region called Argob. They were stubborn places, built on high ground, walls seeming to grow from the living rock. We put them under the ban, a solemn, awful duty.

After the fighting, there was the counting, the distribution. We took the livestock and the plunder from the towns for ourselves. But the land… the land was vast. From the Arnon Gorge, a deep scar in the earth, all the way north to Mount Hermon, which the Sidonians call Sirion, and the Amorites call Senir. All the towns of the plateau, all of Gilead, and all of Bashan. I stood on a ridge overlooking this new territory, this fat land of rolling hills and deep soil, so different from the desert that had shaped our bones. It was a prize, but it was also a responsibility.

So I called the Reubenites and Gadites. They had massive flocks, and they saw the land of Jazer and Gilead, and it was good for livestock. Too good. They came to me with a proposal: let us settle here, east of the Jordan. Do not make us cross over. My first reaction was a hot flash of the old anger, the kind I felt when Israel worshipped the calf. It felt like abandonment, like choosing comfort over the promise. But they were shrewd. “We will build sheepfolds for our livestock and cities for our little ones,” they said. “But we, every man who is armed for war, will cross over before the people of Israel, until we have brought them to their place. We will not return to our homes until every one of the people of Israel has obtained his inheritance.”

They would be the vanguard. They would bear the brunt of the fighting west of the Jordan, while their families and wealth remained safe here, in the conquered land. It was a fair deal, a hard deal. I agreed, but with stern conditions sworn before the Lord. “If you do this,” I told them, my voice gravelly with the weight of it, “if you take up arms and go before the Lord until he has driven out his enemies… then afterward you shall return and be free of obligation to the Lord and to Israel, and this land shall be your possession.” I warned them, too. The consequences of failure would cling to them like a curse.

So I divided it then. To Reuben and Gad the southern part, from Aroer on the Arnon, and half the hill country of Gilead. To the half-tribe of Manasseh I gave the rest of Gilead and all Bashan, the region of Argob. Jair, a man of Manasseh, took all the region of Argob, that land of sixty great cities. We called it Havvoth-jair, the villages of Jair, to this day. Machir, I gave Gilead. It was settled, apportioned, done.

And then… then came the hardest moment. It was after the allotments were made, after the tribes had begun to plan their settlements. The Lord said to me, “You have seen all that I have done. Now it is Joshua who will lead this people across. He will cause them to inherit the land which you see.” It was a confirmation and a sentence in the same breath. The promise was real, tangible, just over that river. I could see the hazy outline of the hills of Judah in the distance. I could almost smell the orchards.

A desperation rose in me, a raw, human ache that pushed aside the dignity of a prophet. I pleaded with the Lord. “O Lord God,” I prayed, my face pressed into the dry earth of the plains of Moab, east of the Jordan opposite Jericho. “You have only begun to show your servant your greatness and your mighty hand. What god is there in heaven or on earth who can do such works and mighty acts as yours? Please, let me go over and see the good land beyond the Jordan, that good hill country and Lebanon.”

The answer was immediate, and it was final. It was not shouted. It was a closing door. “Enough from you; do not speak to me of this matter again. Go up to the top of Pisgah and lift up your eyes westward and northward and southward and eastward, and look at it with your eyes, for you shall not go over this Jordan. But charge Joshua, and encourage and strengthen him, for he shall go over at the head of this people, and he shall put them in possession of the land that you shall see.”

So that is where I am. In the plains of Moab. I have charged Joshua, publicly, before all Israel. “Your eyes have seen all that the Lord your God has done to these two kings,” I told him, the people listening. “So will the Lord do to all the kingdoms into which you are crossing. Do not fear them, for it is the Lord your God who fights for you.” The words were for him, but they echoed in the hollow place inside me. The fighting is done for me. My work is to write this down, to tell the story, to make them remember. To prepare them to cross over without me. They will look to the new leader, to Joshua, with his calm eyes and ready sword. And I will look from Pisgah, see the land with my old eyes, and be gathered to my people. It is a good land. A land of hills and valleys, drinking water from the rain of heaven. The Lord will bring them in, and I will remain here, on this side of the river, with the memory of iron beds and the smell of conquered earth.