The air in Samaria held the peculiar thickness that comes before a storm, a damp, metallic taste that hinted at more than rain. Eliam shifted his weight on the rough stone of the city wall, his eyes scanning the horizon not for weather, but for meaning. Below him, the city clattered and hummed, a noise like a bronze vessel dropped on flagstones—busy, hard, and ultimately hollow.

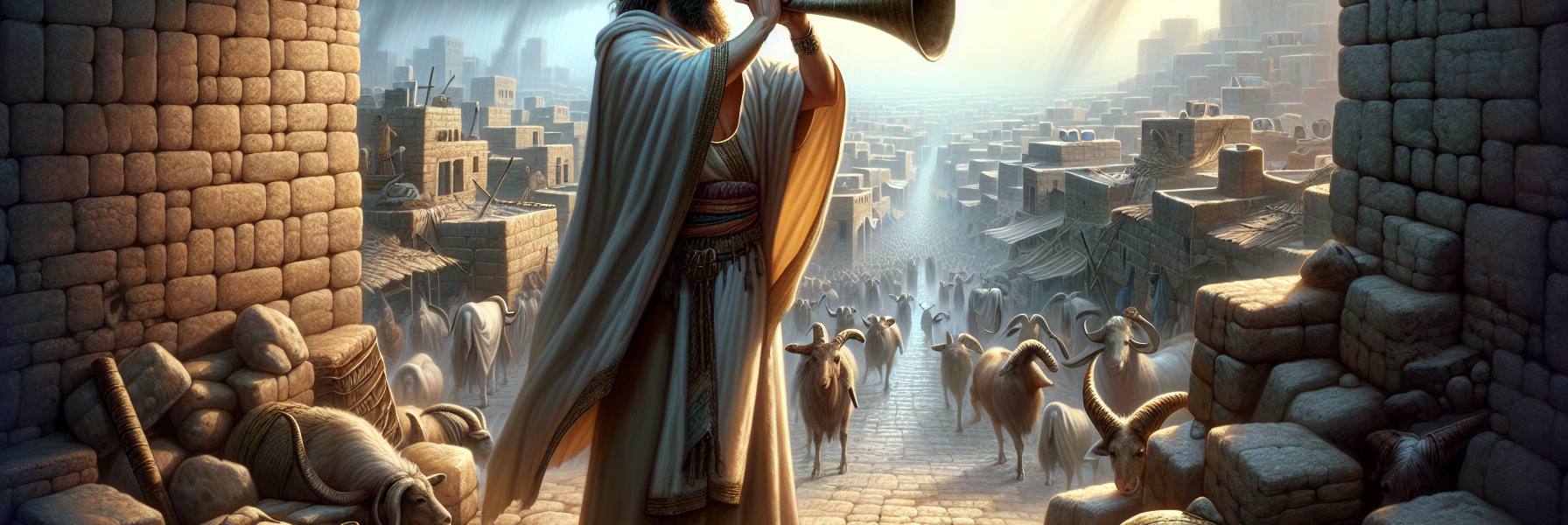

“Set the trumpet to your lips!” The words of the Lord were not a shout in Eliam’s soul, but a cold, sharp pressure, like a blade point against his ribs. The warning was to be given. He had done it before. They would not hear it now, any more than they had then. They would hear only the blast, mistake it for a festival fanfare, and return to their business.

He raised the ram’s horn, its curve familiar and worn smooth by his own father’s hands. The sound he blew was not clean or martial, but a ragged, tearing cry that scraped across the rooftops. A few heads turned in the market square. A merchant shielding a clay lamp from the gusty wind glanced up, squinted, and went back to haggling. The sound was absorbed into the noise of a kingdom busy with its own version of survival.

*Like a vulture over the house of the Lord.* The thought came to him, unbidden and perfect. They were not being attacked from outside yet; they were being circled from above. Their transgressions had a weight, a specific gravity, and it was pulling the shadows of carrion birds across the sun.

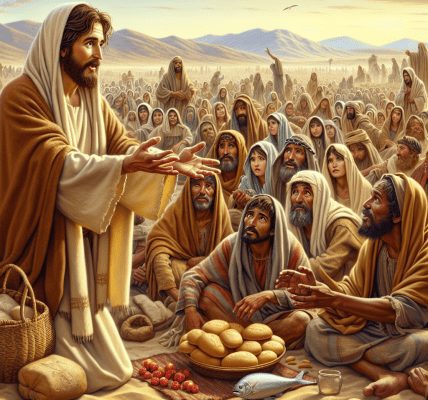

He descended into the streets, the prophet a ghost among the living. He passed the new altar in the square of the calves. It was handsome, made of dressed stone from the quarries near Shechem. Priests in linen moved with practiced grace, and the smell of burning fat was rich in the air. A man in a fine wool tunic pressed forward to present a lamb, its fleece dyed red for the sacrifice. The ritual was flawless, a masterpiece of human devotion. And it was an abomination. It was a treaty signed with a power that did not exist, a desperate plea thrown into a well with no bottom. *They have set up kings, but not by me; they have made princes, and I knew it not.* The king in his palace, Menahem, was a man of grasping ambition who had bought his throne with Assyrian silver, tribute squeezed from the poor to pay a foreign overlord for the privilege of being a puppet. The kingdom’s sovereignty was a beautifully painted clay pot, already fractured from within.

Eliam watched a craftsman in a stall by the gate, finishing a small silver figure of a bull. The man’s hands were skilled, the details exquisite—the curve of the horn, the musculature of the neck. It was a thing of art, and people would pay good shekels for it. They would take it home, place it on a shelf, and whisper prayers for fertility, for rain, for protection. *The workman made it; therefore it is not God.* The absurdity was a physical ache. A man pours his own skill, his own breath, into an object, and then bows down to it, begging it to be the source of the very breath in his lungs. Israel had forgotten the maker in love with the thing made.

He walked out of the city gate, into the fields. Here the consequence was not yet masked by incense and silver. The wheat was thin, the heads sparse. The wind, warmer now, carried the scent of dust, not of rich soil. *For they sow the wind, and they shall reap the whirlwind.* They had planted strategies of political alliance with Egypt and Assyria, seeds of faith in their own craftsmanship and military walls. They had sown emptiness, and the harvest would be a force that would strip everything bare. The standing grain would have no yield; if it yielded, foreigners would swallow it. It was a closed circle of futility.

He came to a high place, an old shrine now repurposed. The stones of the altar were blackened by many fires. Scattered around it were the fragments of other stones—the tablets of the law, perhaps, or simply the markers of a covenant nobody could remember. A people who break covenant before the ink is dry, who run to every new whisper of power, are a people who build with rotten timber. Their alliances were like a spider’s web, impressive in the morning dew, gone by midday. They had gone up to Assyria, a wild donkey wandering alone, hiring lovers from among the nations. But the hireling’s loyalty lasts only as long as the payment. The king of Assyria would remember the tribute, not the friendship.

Eliam sat on a cold stone. The vision the Lord had given him was not of fire from heaven, but of a slow, relentless decay. *They multiply altars for sinning.* Every attempt to atone through their own methods only built another monument to the separation. It was a bureaucracy of alienation. And the beautiful, meticulous laws given at Sinai? They regarded them as a strange thing, an archaic document. The words of the prophet were a foreign language.

The storm, when it broke, would not be a cleansing. It would be a winnowing. The palaces adorned with ivory, the storehouses full of ill-gotten grain, the proud altars—all would be for the burning. *For the fire of his wrath,* Eliam murmured to the gathering wind. Judah, too, was not immune. Fortified cities would be sent a fire, and it would consume her strongholds. Not because God was petty, but because the choice to live outside the reality of His covenant was to choose to live inside a lie. And a lie cannot sustain a life, a family, a kingdom.

He stood, his joints stiff. The first heavy drops of rain began to fall, washing the dust from the withered wheat stalks. They fell on the just and the unjust, on the prophet who understood and the people who would not. The tragedy was not merely in the punishment to come, but in the present, willful deafness. The trumpet had sounded. The vulture circled. And the people, with great skill and devotion, continued to polish the chains they thought were jewelry. He turned his face toward home, the taste of the storm now fresh and cold on his tongue, carrying the scent of a harvest that was nothing but chaff.