The heat was the first thing to leave. For days, the *khamsin* wind had scoured the hills, a gritty, fevered breath that stole the moisture from the olive leaves and turned the dust of the path into a fine, restless powder. Ezra felt it in his bones, a weariness that was more than labor. But as he stood on the threshing floor, wiping his brow with a faded sleeve, he felt it shift. A cooler current, faint as a sigh, drifted down from the high places. He looked up.

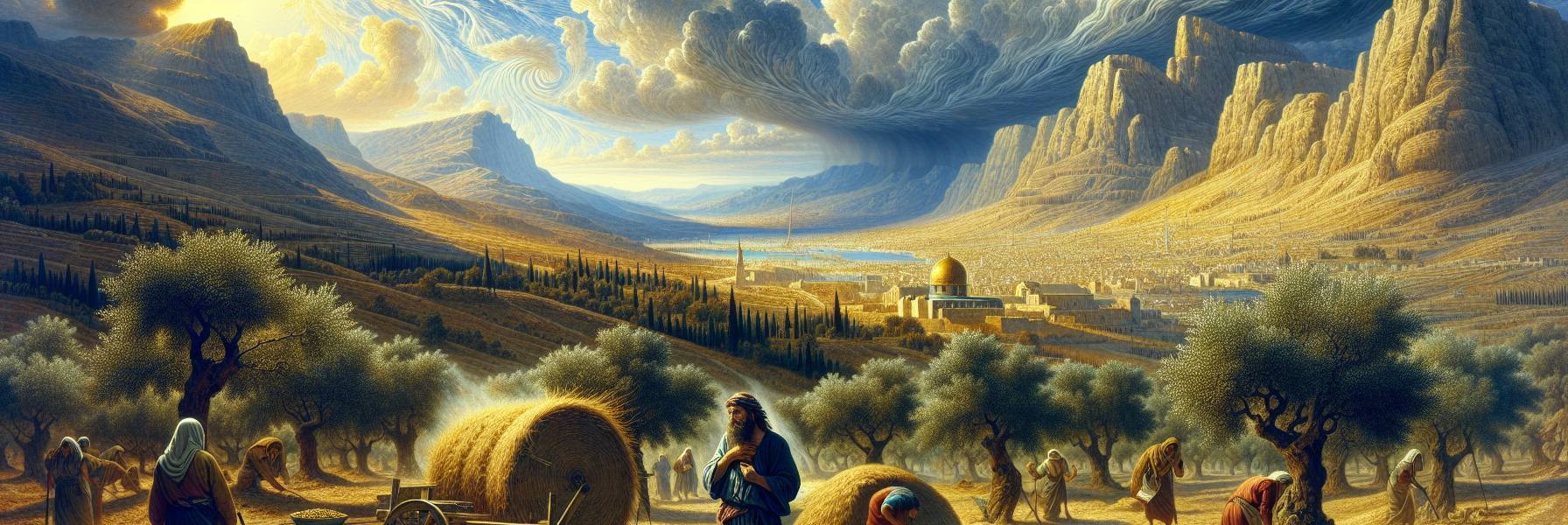

Jerusalem was always there, of course, on its mound of rock to the north. From his family’s strip of land on the western slope, the city appeared as a crown of sun-bleached stone, the Temple a distant, glimmering tooth. But it was the mountains that held his gaze now—the dark, undulating ridges that cradled the city. Mount Zion itself, and around it, the older, taller sentinels: the Mount of Olives, Scopus, the shadowed bulk of what some called the Hill of Evil Counsel. They didn’t seem to move. In all his forty years, through drought and deluge, through the tramp of foreign soldiers and the celebrations of pilgrims, those hills had simply *been*. They were a fixed point in a turning world.

The promise of the cooler air pulled him from his work. He left the flail leaning against the winnowing basket and walked to the low stone wall that marked his boundary. The ache in his lower back protested, a familiar companion. Below, in the valley, the lengthening shadows painted the terebinth trees a deep, cool green. A memory surfaced, unbidden—his grandfather’s voice, rough and sure, as they sat in this very spot. “We are like Zion, boy,” the old man had said, his gnarled finger pointing. “Not like the flash flood in the wadi, here today and gone to the Salt Sea tomorrow. We are set. The mountains are round about her, and so the Lord is round about his people.”

Ezra had nodded then, a boy’s nod, more interested in the fig cake in his hand. Now, the words returned with the weight of lived years. He thought of the fear last harvest, when rumors of bandits from the south had set the village whispering, doors bolted before sunset. He remembered the sick, clawing anxiety when his youngest son, Joab, had burned with fever for three nights, his small body trembling like a leaf in a storm. In those moments, Ezra had not felt like a mountain. He had felt like the dust the *khamsin* scattered.

Yet, here he was. The bandits had never materialized. Joab’s fever had broken with the dawn of the fourth day, the boy’s eyes clearing like a sun-washed sky. The olive trees, though parched, had yielded enough. The house still stood. It wasn’t a dramatic deliverance, not a parted sea or a crumbling wall. It was a continuity. A stubborn, simple remaining. Like the hills.

He watched a hawk circle on a thermal over the valley, its wings perfectly still. The scepter of the wicked, his grandfather would have called it. Ezra understood that now, too. It wasn’t always about armies or kings. The “wicked” could be the creeping despair that told a man his labor was worthless. It could be the corruption that leeched fairness from the marketplace, the casual cruelty that made the poor feel invisible. It was the impulse to grasp, to dominate, to bend the land and its people to a selfish will. That scepter could rest on a man’s heart as surely as on a ruler’s staff.

But the hawk moved on. The thermal failed, and the bird wheeled away toward the rugged wilderness to the east. It would not nest in the fruitful places. The rule of the wicked, however it manifested, was not the permanent thing. It was the *khamsin*—fierce, oppressive, but passing. The land itself, like the Lord’s justice, outlasted it.

A soft call came from the house. His wife, Miriam, stood in the doorway, a clay water jar balanced on her hip. “The light is fading, Ezra. Come and eat.”

He turned from the view, his muscles protesting again as he moved. He was not a mountain. He was a man, tired and sore, his hands cracked from work. But as he walked back toward the lamplight spilling from his home, toward the voices of his children squabbling over the best piece of barley bread, he carried a quiet conviction. His trust was not in the unyielding stone of the hills themselves, but in what they represented. They were a picture, a divine metaphor etched into the very landscape of his life. He was surrounded. Not just by topography, but by a faithfulness as ancient and present as the rock beneath his feet.

The night settled, cool and deep. In the house, a simple psalm of blessing was murmured over the meal. Outside, the mountains around Jerusalem were swallowed by the darkness, unseen. But their presence was a felt thing, a vast, silent watchfulness. And in the stillness, Ezra knew a peace that was not the absence of trouble, but the profound, enduring presence of something—of Someone—infinitely more steadfast. For the righteous, the path might be long and often difficult, but it was a path that held. It would not, could not, slip into the shadows forever. The mountains stood. And so, by grace, would he.