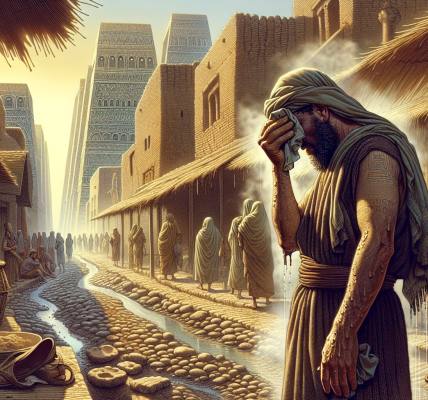

The heat rose from the stones of Anathoth in visible shimmers, a stifling blanket that did nothing to muffle the noise drifting from Jerusalem, a few miles distant. Baruch found the prophet where he often did these days, not in the house, but under the broad, gnarled fig tree that clung stubbornly to the hillside. Jeremiah was not praying, not in any formal sense. He was staring south, his eyes fixed on nothing and everything, the scroll of his words lying unopened in the dust beside him.

“They are bringing the firstfruits to the Temple today,” Baruch said quietly, settling on a lower stone. He offered a clay cup of water. Jeremiah took it, his movements slow, as if weighed down by a sack of millstones.

“The sweet figs are gathered,” Jeremiah said, his voice a dry rasp. “But the basket is full of rot. They offer the season’s first, but their hearts are the last of the harvest, withered and sour.” He drank, then let his hand fall. “They sing the psalms of ascent. ‘Who may ascend the mountain of the Lord?’ Do you hear it, Baruch? A faint buzzing, like flies over a forgotten sacrifice.”

Baruch listened. He heard only the cicadas and the distant, indistinct murmur of the city. But he had learned to hear with Jeremiah’s ears.

“I have seen the summer pass,” Jeremiah murmured, not to Baruch, but to the hills, to the sky, to the God who had planted this fire in his bones. “The harvest is ended, the stubble is dry, and we are not saved. Why is that? Why does this people persist in apostasy? They hold fast to deceit; they refuse to return.”

He stood abruptly, a gaunt figure against the bleached sky. “I have listened. In the courts, in the gates, in the shadow of the palace. They say ‘Peace, peace,’ when there is no peace. Are they ashamed of their abomination? No, not at all. They cannot even blush. They will fall among the fallen. When I would gather them, says the Lord, there are no grapes on the vine, no figs on the fig tree. Even the leaves are withered.”

Baruch watched as his friend began to pace, a caged lion with an invisible cage. The words were not new—he had inscribed them himself—but hearing them breathed into the heavy air was different. They were alive, and they carried the scent of death.

“They dress the wound of my people as though it were slight. ‘All is well,’ they say. ‘All is well.’ But the sickness festers in the bone. It flows into the blood. They look to the carved stones on the high places, they consult the moon and the stars that their God made for seasons. They seek life from the quarter of death. And the wise… oh, the wise.” Jeremiah stopped, a bitter laugh escaping him. “The wise are put to shame, dismayed, and trapped. They have rejected the word of the Lord, so what wisdom do they have? They are skilled in doing evil, but how to do good they know not.”

A silence fell, deeper than before. The distant sounds of celebration felt like a mockery. Jeremiah’s shoulders slumped. The prophet was gone; only a weary man remained. “My heart is sick within me,” he whispered, the anger drained away into a boundless grief. “Listen. Can you hear it? From Dan in the north, the news of the horsemen. From the hills of Ephraim, the sound of the enemy singing their own songs. They are coming, Baruch. A hissing, a venom, serpents that cannot be charmed. Their teeth are spears and arrows, their tongue a ruthless sword.”

He turned, and his eyes were pools of a sorrow too deep for tears. “What is left for us? Is there no balm in Gilead? Is there no physician there? Then why has the healing of my people not come? Why does the wound not close?”

Baruch had no answer. He looked at the ground, at the cracks in the earth where no green thing grew. Jeremiah sank back to his seat under the fig tree, his energy spent. He picked up a handful of dust and let it trickle through his fingers.

“The harvest is past,” he said, so softly Baruch almost didn’t hear. “The summer has ended. And we are not saved.”

They sat together as the sun began its slow descent, casting long, distorted shadows. The joyful noise from Jerusalem eventually faded, replaced by the ordinary sounds of evening: a goat bleating, a mother calling a child, the first chill whisper in the olive leaves. The promised calamity was not here, not yet. But in the prophet’s silence, in the very air that now tasted of coming autumn, it was as real as the stone beneath them. It was a story written not in ink, but in the unblinking eye of heaven, a narrative of a people who had forgotten how to return, and of a God whose patience had found its limit, etched in the relentless, unfolding truth of a day like any other.