The air in the court of King Jotham tasted of dust and damp stone. It was not the clean dust of the desert, but the grime of a city too long under a slack hand, the mildew of justice delayed. Jotham, they called him. A good name, meaning “The Lord is Perfect.” He sat on the cedar throne his father had built, its carvings of lions and pomegranates worn smooth by generations of anxious hands. His own hands lay still on the armrests, but his eyes, the colour of a winter sky, were restless. They scanned the scroll unfurled on his lap—not a tax ledger or a military report, but the words of the proverb-writer: *“When the righteous are in authority, the people rejoice; but when a wicked man rules, the people groan.”*

A groan seemed to hang in the very air of the chamber. It was in the slump of the guards’ shoulders, in the muttered petitions from the antechamber, in the way the merchants in the lower city haggled with a desperate, joyless fervor. Jotham knew the source. Not a foreign army at the gates, but a slow rot within. His own cousin, Sheva, the Prefect of the Walls, was a man whose scales were tipped with lead. Sheva took a “silver consideration” for favorable judgments, and his officials, like a pack of dogs who’ve caught the scent of a master’s weakness, followed suit.

In the lower city, in a house that leaned against the city wall as if for support, lived a widow named Tamar. Her two rooms were dark, the window small, but a single clay lamp burned late. She was teaching her son, Avi, to read. The text was the same one the king pondered. *“The king by judgment establisheth the land: but he that receiveth gifts overthroweth it.”* Avi’s finger traced the words. “Why do they take gifts, Ima?” he asked. Tamar, her face lined more by thought than by years, said, “Because they have forgotten the fear of the Lord. They see only the glitter in the hand, not the collapse of the wall.”

Sheva was not an evil man in his own mind. In his spacious house on the upper hill, he felt pragmatic. The kingdom needed revenue. The system needed oil to function. A little silver here, a discreet arrangement there—it was how things worked. His own son, Eran, a young man with a loud laugh and empty eyes, embodied another proverb: *“He that being often reproved hardeneth his neck, shall suddenly be destroyed, and that without remedy.”* Old Nathan the scribe had reproved him just that morning for cheating at the chariot races. Eran had scoffed, tossing a date pit in the old man’s direction. Sheva had seen it and said nothing, a silent endorsement that chilled Nathan more than any shout.

The crisis came not with a fanfare, but with a stifled cry. Tamar’s neighbor, Reuben, a potter, had his stall confiscated by one of Sheva’s men for a “violation of market space.” The space was paid for. The violation was his refusal to pay a new, invented fee. Reuben, a gentle man, saw red. He stood in the street, clay dust on his tunic, and shouted the corruption aloud. *“A fool uttereth all his mind: but a wise man keepeth it in till afterwards.”* Sheva’s guards, embarrassed by the truth in the public square, dragged him not just to the stocks, but to the grim, windowless cell reserved for disturbers of the peace.

That night, Tamar did not light her lamp. She sat in the dark, Avi asleep beside her. The words of the scroll churned within her. *“The righteous consider the cause of the poor: but the wicked regard not to know it.”* She was not a woman of the court, but her righteousness was of a fierce, quiet kind. As the first grey light touched the city, she rose, woke Avi, and told him to go to Nathan the scribe. Then she walked, alone, up the winding streets to the palace gates.

She did not demand. She requested an audience with the king’s steward, citing a matter of inheritance law—a technical truth. Her calmness, her precise speech, gained her entry to an outer courtyard. There, by a fountain where a sparrow drank, she saw King Jotham himself, walking alone, his brow furrowed. He noticed her, a simply-dressed woman standing with a stillness that seemed out of place amidst the palace’s hustle.

“You seek someone?” he asked, his voice tired.

“I seek justice, my lord,” she said, and she did not bow low, but held his gaze. “Not for myself, but for a potter named Reuben, and for the city whose walls are crumbling from within.”

Jotham was silent for a long moment. He saw no guile in her face, only a clear, weary resolve. *“Where there is no vision, the people perish,”* he thought. Here was vision, standing before him in a worn cloak. He listened as she spoke, not just of Reuben, but of the patterns—the fees, the threats, the name of Sheva spoken in whispers like a curse.

Meanwhile, Avi had found Nathan. The old scribe, his heart a mix of fear and long-suppressed fire, took the boy’s hand. He went not to the palace, but to the marketplace. He stood on the very spot where Reuben’s stall had been, and he began to speak. He did not shout. His voice was dry as parchment, but it carried. He spoke the proverbs aloud—the very ones Sheva’s son had mocked. *“The bloodthirsty hate the upright: but the just seek his soul.”* *“An unjust man is an abomination to the just: and he that is upright in the way is abomination to the wicked.”* A crowd gathered, not a riotous mob, but a somber assembly of merchants, porters, and housewives. They listened. They nodded. A low, affirming murmur rose from them, a sound more powerful than any groan.

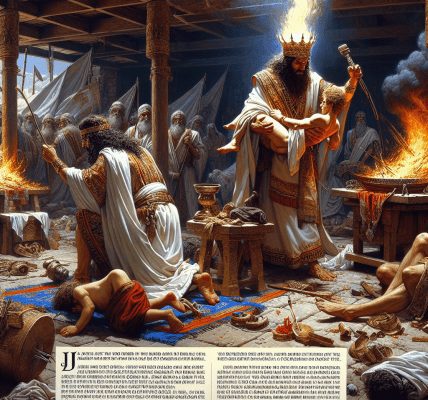

Back in the palace, Jotham acted. He did not send soldiers. He sent messengers, summoning Sheva, his officials, and the imprisoned Reuben to the throne room. He also sent for Nathan and the widow Tamar. The court assembled under the high ceiling, a tense tableau.

Jotham did not rant. He simply had Nathan read from the scroll. The scribe’s voice filled the silent hall. *“Many seek the ruler’s favour; but every man’s judgment cometh from the Lord.”* *“The fear of man bringeth a snare: but whoso putteth his trust in the Lord shall be safe.”* Each verse fell like a plumb line against the crooked dealings of Sheva’s administration. Sheva, confronted not with wild accusations but with the unwavering standard of the wisdom he claimed to revere, had no defense. His face drained of colour. He saw his son Eran in the crowd, the young man’s arrogant smirk now frozen into a mask of terror. *“He that delicately bringeth up his servant from a child shall have him become his son at the length.”* But Sheva had brought up his son on delicacy and corruption, and now he reaped the harvest.

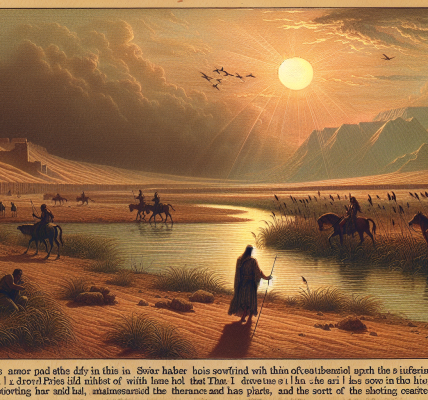

Judgment was pronounced. Sheva was removed, his wealth restored to the treasury. Reuben was freed, his stall returned. The reforms were slow, meticulous. But the change in the city’s air was swift. It was as if a thick, foul mist had lifted. Laughter returned to the market, not the shrill laughter of anxiety, but the genuine sound of commerce and community.

Jotham often walked the lower city now. He saw Tamar and Avi, their lamp burning bright in their window. He saw Nathan, teaching a group of children under a fig tree. The king had learned that authority was not about the throne, but about the posture of the heart. *“A man’s pride shall bring him low: but honour shall uphold the humble in spirit.”*

Years later, when Avi was a young man known for his integrity, he walked with his own son past the palace. The boy asked about the old king, Jotham. Avi thought for a moment, listening to the sounds of a city at peace—the clink of a blacksmith’s hammer, the call of a vendor selling fresh figs, the distant song from the temple.

“He was a king who learned to listen,” Avi said. “He learned that a ruler who shuts his ear to the cry of the poor, he too will cry one day and not be heard. But a man who heeds wisdom, even when it speaks from a dusty street… his light endures.” And as they walked on, the last of the sunset caught the white stones of the palace wall, setting them ablaze for a moment, a brief, beautiful testament to what can be built when the foundations are just.