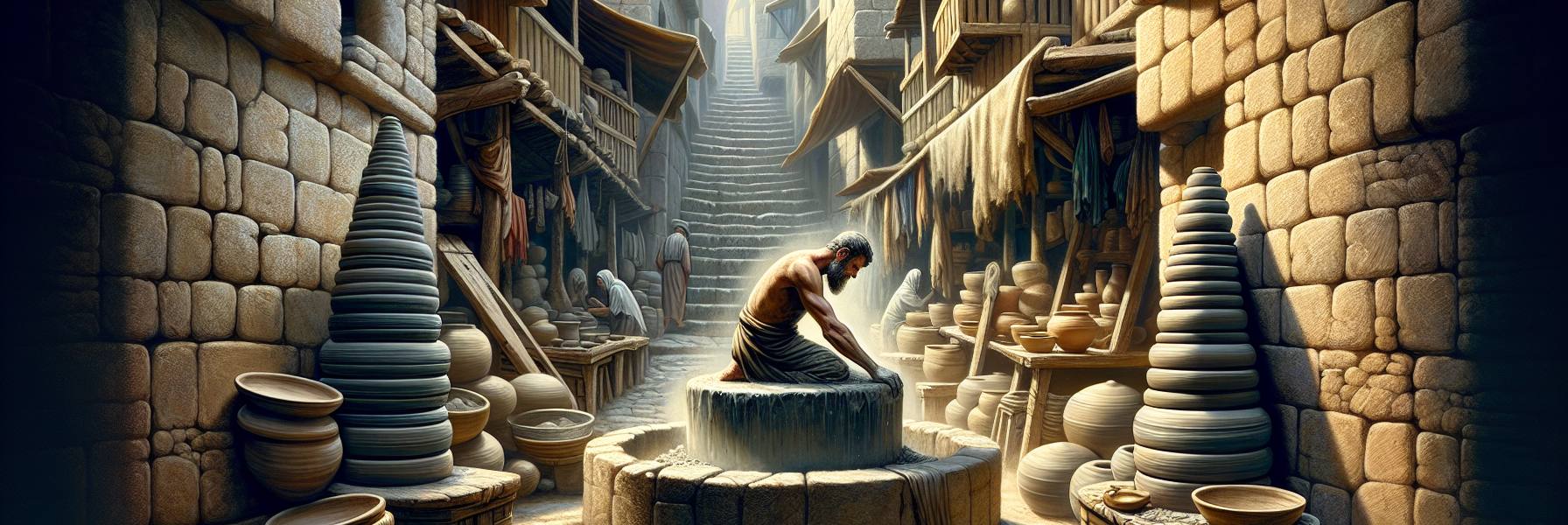

The heat in the potter’s quarter was a thick, dusty thing. It clung to the back of Jeremiah’s throat as he picked his way down the stepped street, the cries of bartering merchants and the clatter of carts fading behind him. He wasn’t looking for wares. He was following a weight, a quiet, insistent pressure behind his ribs that had become as familiar as his own breath. It led him away from the grand thoroughfares, into a narrower lane where the buildings leaned in, their shadows offering scant relief. The air here smelled different—damp earth, mineral, the faint, acrid scent of ash from a kiln’s mouth.

He found the workshop in a small courtyard, open to the sky. A man, his forearms corded and streaked with grey slurry, sat before two heavy stones. The lower one was fixed, the upper turned by a kick of his foot, spinning with a low, grinding rhythm. Jeremiah paused in the archway, unnoticed. He watched.

The potter’s hands were everything. They cradled a shapeless mass of dark clay centred on the wheel. As the stone turned, those hands applied a firm, encompassing pressure. A cylinder rose, wobbling slightly, an obedient thing responding to will. The potter’s thumbs pressed into the top, opening a hollow. Now the motion changed; one hand cupped the outside, the other slid inside the emerging vessel, and between them, with a subtle, unceasing tension, the wall grew taller, thinner, graceful. It was becoming a jug, perhaps for oil or wine, its form flowing upward from the spinning core.

Then, without warning, a grit—a pebble unseen within the clay—betrayed the work. The smooth wall snagged, tore. The symmetry shattered into a lurching, uneven wobble. The potter did not curse. He did not sigh. His foot stopped. He simply looked at the spoiled thing for a moment, his head tilted. Then, with a decisive, merciful motion, he collapsed the failing vessel back into a wet, amorphous lump. He kneaded it thoroughly, working the moisture, pressing out the flaw. He began again.

Jeremiah felt the words form, not in his mind, but in that same deep place from which the pressure had come. They were not his own. They were a echo of the grinding stone, a truth spoken in the language of hands and mud.

“Arise,” the pressure said within him, “and go down to the potter’s house. There I will let you hear my words.”

He was already here. The hearing was in the watching.

The potter, sensing a presence, glanced up. His eyes were the colour of the clay, and they held a patient exhaustion. Jeremiah stepped forward, his own rough tunic brushing against a drying shelf where finished bowls sat, their rims perfect and waiting.

“What do you see, Rabbi?” the potter asked, his hands still working the revived clay. A new form was beginning, lower, broader—a sturdy bowl for a common table.

Jeremiah’s voice was rough. “I see a maker. And the thing made. I see the thing fail in his hand. And I see him… begin it again.”

The wheel turned. The bowl’s shape settled, sure and strong. “The clay,” the potter said, wiping his brow with a cleaner part of his arm, leaving a smudge, “it must be pliable. It must yield. If it is stiff, or full of stones, it is only good for the pugging pit. A man can only work with what the clay allows, and what his skill can salvage.”

Then the voice of the Lord came to Jeremiah, not as thunder, but as the clear, terrible meaning of the scene before him.

“O house of Israel, can I not do with you as this potter has done? You are in my hand like the clay in the hand of the potter.”

The words unfolded in Jeremiah’s spirit. He saw not just the little courtyard, but the hills of Judah, the walls of Jerusalem, the kingdoms of the earth. They were all moist clay on a cosmic wheel. A nation, lifted up for beauty, for purpose, could turn to evil. It could become marred by the hard, unseen stones of idolatry, of injustice, of hollow ritual. And the Potter, in His sovereign wisdom, could choose to collapse that rising form. He could rework it. He could, in His patience, begin again, shaping from the same material a different vessel, fitted for a different purpose. The destruction was not annihilation; it was the necessary collapse before the remaking.

But there was more. The metaphor cut both ways. The Potter’s hands were also responsive. If He spoke of shaping a nation for uprooting and tearing down, and that nation, hearing the warning, truly turned from its evil? Then He would relent. The design would change. Conversely, a nation promised blessing, if it then strayed into pride and corruption, would find its promised form altered to one of judgement. The wheel kept turning; the hands kept shaping. The final form was not fixed by fate, but by the interaction of divine will and human pliability.

Jeremiah stood there long after the understanding had washed over him. The potter finished his bowl, cut it from the wheel with a wire, and set it aside. The kick-wheel slowed to a stop. The silence was full of the meaning of the spinning.

He left the courtyard as the afternoon light slanted gold, the weight in his chest now a specific, aching message. He would have to speak this. He would have to tell them they were not immutable, not irrevocably destined, but were, moment by moment, being shaped in hands that were both ruthless and infinitely tender. They would have to be told they contained unseen grit that could tear them apart, and that the collapse, if it came, was not the end of the material, only of its prideful, flawed form.

He walked back into the clamour of the city, the words of the potter’s house already arranging themselves into a lament and a warning—a prophecy spun from the sight of two hands, a wheel, and the humble, terrifying obedience of clay.