The heat in Babylon that summer was a physical weight, a dry, dusty hand pressing down on the city of exile. For Ezra, the scribe, the heat was secondary to the fire burning in his own spirit. The decree of Artaxerxes was in his possession, a startling scroll of royal authority and provision for the house of God in Jerusalem. But now came the real work: the gathering.

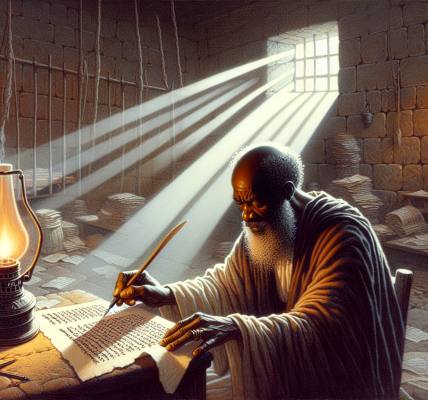

He began at his own doorstep, with the heads of the clans. He sent word, not with royal fanfare, but with the quiet urgency of a summons to a pilgrimage. They came to him in ones and twos, men with the dust of Mesopotamia on their sandals and the memory of Zion in their eyes. Gershom, of the line of Phinehas. Daniel, of the line of Ithamar. Hattush, a descendant of the kings themselves, a quiet man who carried the ghost of Judah’s monarchy in his bearing. The list formed slowly, painstakingly, as Ezra unrolled a fresh parchment and recorded each name. He wrote not just the man, but his father’s house, anchoring each to the great, branching tree of Israel. It was a small company. Not the thunderous host of the first return under Zerubbabel, but a deliberate, scholarly caravan. Fifteen hundred men, perhaps two thousand souls when women and children were counted. A remnant of a remnant.

A silence grew in the midst of the planning. Ezra noticed it first in the prayers. They prayed for the way, for the king’s favor, for the treasures they were to carry. But no one spoke of the Levites. Not a single Kohathite, Gershonite, or Merarite had stepped forward. It was a gaping absence. The temple needed its singers, its gatekeepers, its men to handle the sacred vessels. What was a journey to restore worship without its ministers?

Ezra dispatched messengers to a place called Casiphia, where a community of temple servants and Levites was said to dwell under the leadership of a man named Iddo. The request was simple: send us servants for the house of God. The wait was tense. Days passed. Then, through the Babylonian haze, a group approached. Leading them was Sherebiah, a man with intelligent eyes and a Levite of discernment, and with him, Jeshaiah, and eighteen of their kinsmen. They also brought two hundred and twenty *Nethinim*—the temple helpers whose lineage stretched back to the days of David. It was not a multitude, but it was enough. A fragment of the Levitical spirit had stirred.

They assembled at last by the canal of Ahava. The water was sluggish, choked with reeds, a far cry from the rushing rivers of Judah. For three days, Ezra camped there, taking stock. He looked over the people, the bundles, the carts. And he saw the problem with devastating clarity. They were carrying a king’s ransom. Silver and gold worth hundreds of talents, and sacred vessels of gleaming bronze. The road west was a haunt of bandits, a wilderness of shadows between the rivers and the mountains. To ask the king for a military escort would be to confess a lack of faith in the very God whose power he had boasted of to Artaxerxes. The contradiction tasted like ash.

On the third morning, with the camp stirring under a pale sky, Ezra called for a fast. There, by the dismal waters of Ahava, he proclaimed a day to humble themselves before their God. They would seek from Him a straight and safe journey, for themselves, and for their little ones, and for all their substance. The words, “for all their substance,” hung in the air. It was a prayer about treasure, yes, but also about the fragile, precious cargo of a community’s hope. The fast was a raw, physical act. The growl of empty stomachs became a collective prayer. The dry throats and light heads were an offering. They did not plead for a miracle of destruction upon enemies, but for the quieter, more profound miracle of an uneventful journey.

When the fast was broken, Ezra took the step that committed everything. He chose twelve of the leading priests, and with Sherebiah and Hashabiah and ten of their kinsmen, he weighed out the treasure. The scene was solemn, almost mundane. Scales were brought. The silver, the gold, the vessels were carefully portioned and counted. The weight of every item was recorded. It was an act of bureaucratic holiness. “You are holy to the Lord,” Ezra told them, his voice low but carrying in the stillness. “The vessels are holy. The silver and gold are a freewill offering. Guard them. Watch over them until you weigh them again within the chambers of the house of the Lord, in Jerusalem, in the presence of the chief priests and the Levites.”

The responsibility settled on the men like a mantle. They accepted it with nods, their faces grave. The treasure was no longer just cargo; it was a sacred trust, a fragment of God’s glory entrusted to their hands.

Then, they moved. The caravan uncoiled itself from the banks of Ahava and turned its face toward Jerusalem. The Babylonian plain gave way to harder ground. The journey was a psalm of dust and thirst and aching feet. Ezra’s journal, had he kept one, would have noted the small mercies: a well that hadn’t gone dry, a night passed without the cry of alarm, a child’s laughter from a wagon. The hand of their God, he knew, was upon them. It was not in pillars of fire, but in the absence of disaster. He delivered them, the scripture would later say, from the hand of the enemy and from ambush by the way. The deliverance was invisible, woven into the fabric of uneventful days.

After four months of travel, the land began to change. The hills rose, familiar scents of terebinth and myrtle were carried on the wind. And then, from a high ridge, they saw it: the city on the hill, its walls still broken, but its outline etched against the sky. Jerusalem.

They did not enter in triumph. They entered in exhaustion and profound gratitude. For three days they simply rested, the dust of the long road settling around them in the unfamiliar rooms of the city. On the fourth day, the reckoning came. In the house of God, amidst the raw stone of the still-incomplete temple, the silver, the gold, and the vessels were brought forth. The same priests and Levites stood before Meremoth, son of Uriah, and Eleazar, son of Phinehas. The scales were produced again.

They weighed everything. Every shekel matched the record from the banks of the Ahava canal. Nothing was missing. Not a single bracelet, not a single dish. In that moment, the entire journey telescoped into that single, perfect accounting. The fast by the dismal water, the weary miles, the silent watches of the night—all of it was confirmed in the quiet *clink* of weight against weight in the house of God.

Then, and only then, did they offer. Burnt offerings for a nation, sin offerings for their muddy, imperfect hearts. They presented the king’s decrees to his satraps and governors, and these men, seeing the seal and the substance, gave practical support to the people and the house of God. The treasure was safe. The people were home. The story, Ezra knew, was just beginning again. But this chapter, the chapter of the gathering and the going and the guarding, was closed with the sweet, acrid smell of smoke rising from the altar, a scent that finally, after so long, smelled like home.