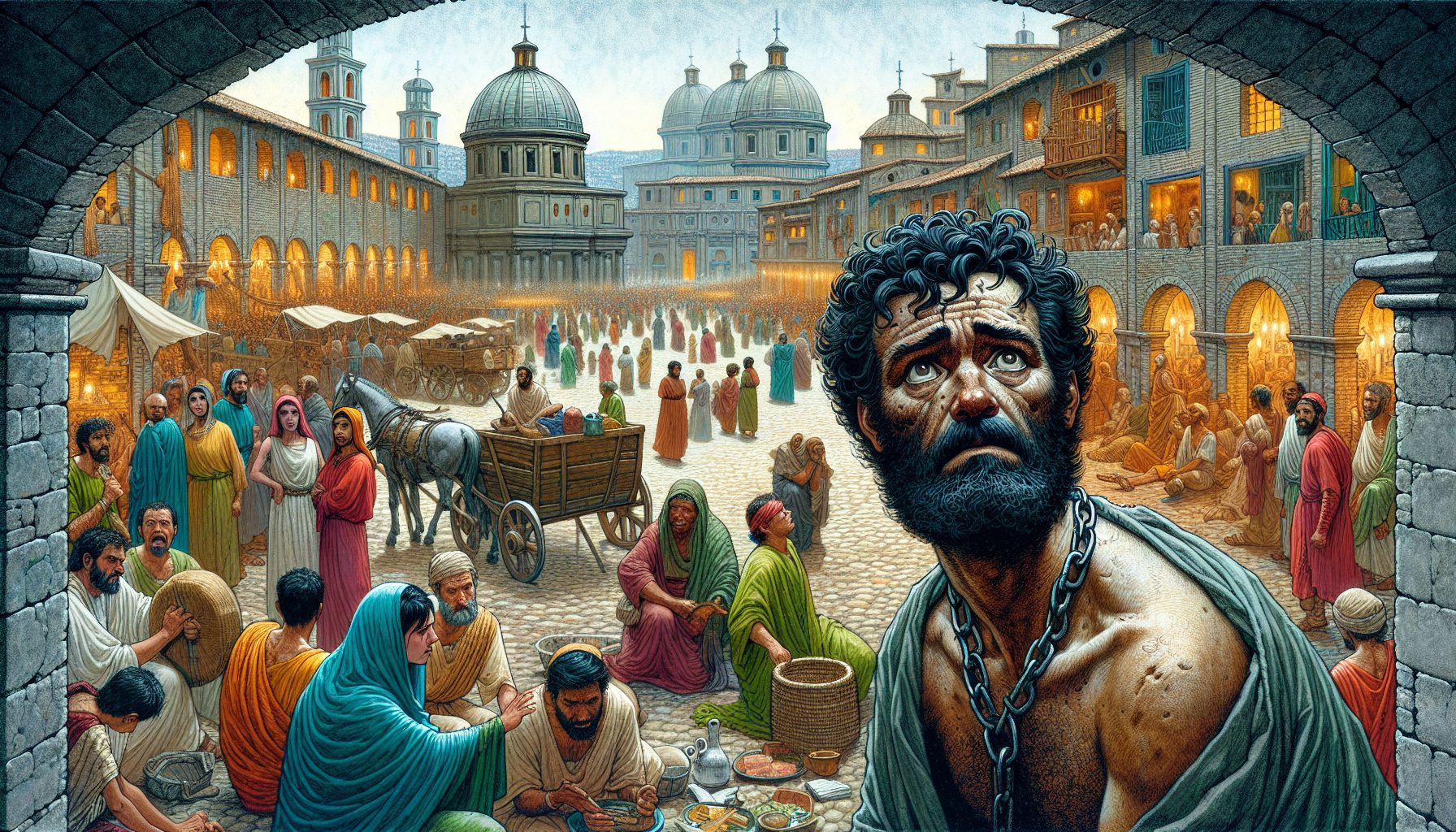

The road down from the Mount of Olives was a scar of dust and despair. David’s feet, shod in sandals worn thin, moved with the heavy, plodding rhythm of a man walking to his own tomb. The sound behind him was a low, mournful symphony—the shuffle of hundreds of loyalists, the occasional snort of a donkey, the clink of weaponry. The air smelled of sweat, of dry earth, and of fear.

He had just passed Bahurim, a village of Benjaminites, when the voice cut through the haze of grief. It was not a shout, but a raw, projecting curse, the kind used to drive evil from a field.

“Get out! Get out, you man of blood! You scoundrel!”

David stopped, the company bunching up behind him. A man was scrambling down a terraced hillside, his tunic flapping. He was old, but spry with malice, his face a knot of fury. In his hands he held not stones, but the dirt of the field, clods of earth and small, sharp pebbles. It was Shimei, son of Gera, of Saul’s house.

The curses fell like the pebbles he hurled. “The Lord has repaid you for all the blood of the house of Saul, in whose place you have reigned! The Lord has given the kingdom into the hand of your son Absalom! See, your ruin is upon you, for you are a man of blood!”

A pebble struck David’s shoulder. Another stung the cheek of a nearby soldier. The air tightened. Abishai, son of Zeruiah, a blade of a man whose loyalty was as sharp as his sword, hissed like a serpent. “Why should this dead dog curse my lord the king? Let me go over and take off his head. Just say the word.”

David placed a hand on Abishai’s arm, feeling the coiled tension in the muscle. The king’s face was grey with weariness, etched with a sorrow deeper than anger.

“What have I to do with you, you sons of Zeruiah?” David’s voice was low, gravelly from the road. “If he is cursing because the Lord has said to him, ‘Curse David,’ who then can say, ‘Why have you done so?’”

He looked past Abishai, past the furious, humiliated faces of his men, to the gaunt, gesticulating figure on the ridge. Shimei was working himself into a frenzy, his diatribe a torrent of ancient grievances and fresh venom. David saw in him not just one man, but the specter of a past he could never fully bury—the blood of Saul, the blood of Abner, the blood of Uriah. It all rose in the dust Shimei kicked up.

“Leave him alone,” David said, and his words carried a terrible, resigned authority. “Let him curse, for the Lord has told him to. It may be that the Lord will look upon my affliction and repay me with good for this cursing today.”

So they walked on, a king and his company, under a hail of curses and dirt. It was a grotesque procession. Shimei kept pace along the ridge, a screeching shadow, his voice growing hoarse. He threw dust until his hands were empty, then he scooped more. The dust settled on David’s hair, mingled with the sweat on his neck, coated his robes. He became a ghost-king, pale with the earth of the kingdom slipping through his fingers.

David did not hurry. He absorbed the humiliation as a dry field absorbs a bitter rain. Each curse was a sting, a reminder. *Man of blood.* The words found cracks in his soul. He thought of Bathsheba’s husband falling before the Ammonite arrows he had ordered him to face. He saw the grief in the eyes of the few surviving sons of Saul. The prophet Nathan’s voice echoed in his memory, clear as yesterday: “The sword shall never depart from your house.”

Perhaps this, then, was part of the reaping. Not a clean sword in battle, but the slow, public stripping of dignity. A madman from the ruins of Saul’s legacy naming the price of the throne.

They moved along the flank of the valley, the sun beating down. The curses eventually grew ragged, then ceased, replaced by the sound of Shimei spitting in the dust. He fell behind, his vengeance spent for the moment.

But the encounter had changed the air. The company’s silence was no longer just weary; it was stunned, ashamed. Their king, the slayer of Goliath, the sweet singer of Israel, had just eaten dirt and called it the Lord’s will. It was a theology of unbearable humility.

As they drew nearer to the Jordan, to the faint hope of refuge on the other side, David looked back once. Jerusalem was a hazy silhouette, and between him and it, a small, distant figure still stood on the ridge. He turned his face east again, toward the river and the barren beyond. The dust on his shoulders felt like a weight, and also, strangely, like a release. He was carrying the condemnation with him, bearing it away from the city. It was a debt he would not shed, but would instead let wear him down, grain by grain, until heaven itself decided the account was settled. He walked on, a cursed king, his hope a fragile, desperate thing, waiting on the goodness of God from the depths of a very different kind of valley.