The dust of Joppa still clung to Peter’s sandals as he climbed the steep, narrow street toward the house by the sea. It had been a strange season. The memory of Tabitha, cold and still on her bed, then warm and alive again, was a weight and a wonder he carried deep in his bones. But that was not the thing that haunted his steps now. No, it was the dream, the voice, the undeniable, unsettling command that had come to him on that sun-drenched rooftop while he waited for a meal he did not want to eat.

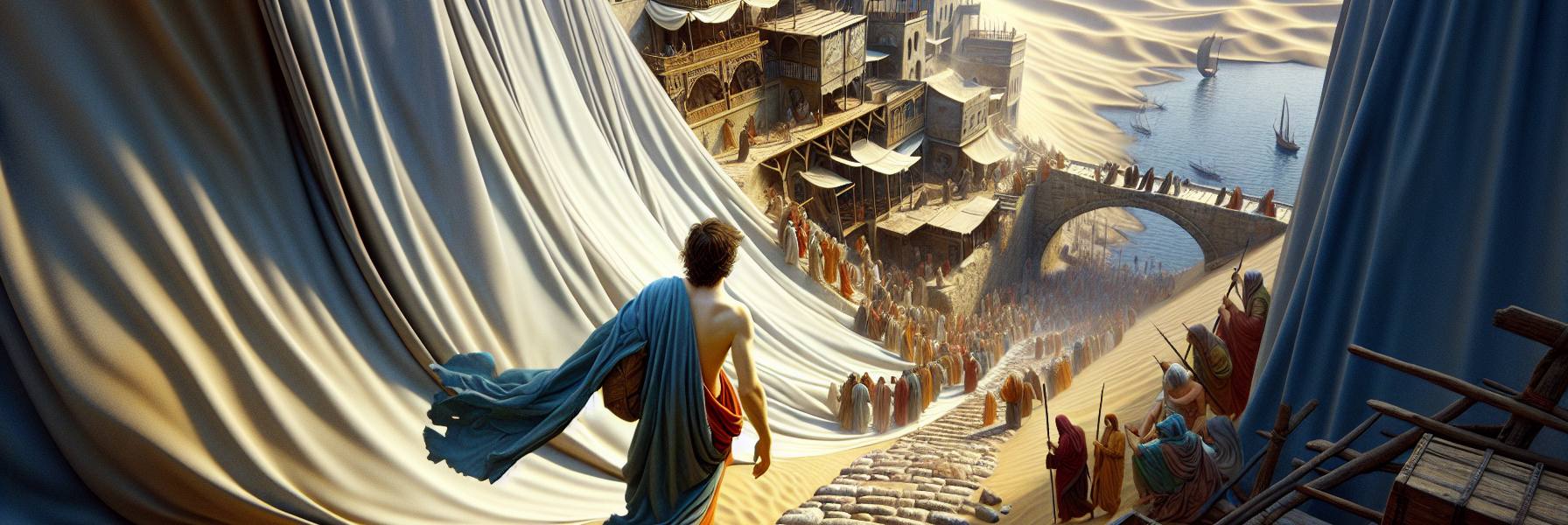

He had been praying, the heat of the day laying a heavy hand on the city, when the world tilted. A great sheet, suspended by its four corners like a vast sail lowered from heaven, descended before him. And in it, a teeming, chaotic menagerie of everything a good son of Israel was taught to reject. He saw the scaly hide of serpents, the cloven hoof of the swine, creatures that scurried and flapped, all tangled together. And the voice, clear as mountain air, said, “Rise, Peter; kill and eat.”

His refusal had been instinctive, a lifetime of devotion distilled into three words: “By no means, Lord.” The voice came again, gentle and absolute, and Peter understood, with a dread that was also a kind of joy, that the vision was not about food. It was about the very boundaries of God’s love. The sheet was drawn back into the sky, and he was left sitting in the sun, his world unmade.

He had barely begun to turn the vision over in his mind when the men from Caesarea arrived, sent by a Roman centurion named Cornelius. A God-fearer, they said, a man who prayed and gave alms, but a Gentile. An uncircumcised man. And the Spirit had spoken to Peter as clearly as it had to Cornelius: “Go with them, for I have sent them.”

So he went. He crossed the threshold of a Roman soldier’s house, a thing he would never have done, and he saw their faces—eager, hopeful, foreign. And as he began to speak to them about Jesus, the very thing that had happened in Jerusalem at Pentecost happened again, here, in this house of Gentiles. The Holy Spirit fell upon them all. They spoke in tongues and praised God. It was undeniable, a torrent of grace that swept away every argument, every regulation, every wall he had ever known.

Now, back in Jerusalem, the air was different. The news had traveled faster than he had. The believers from the party of the circumcision were waiting for him, their faces set like stone.

“You went into the house of uncircumcised men,” one said, his voice low and sharp, “and you ate with them.”

Peter did not rush to defend himself. He felt a profound weariness, the kind that follows a long and difficult journey. He looked at their faces, good men, devout men, men who loved God as fiercely as he did. He began to tell the story, not as a defense, but as a testimony. He wanted them to see it, to feel the disorientation of the vision, the strangeness of the command.

“I was in the city of Joppa, praying,” he began, his voice steady. “And in a trance I saw a vision. Something like a great sheet was let down from heaven by its four corners, and it came right down to me. When I looked inside, I saw all kinds of four-footed animals and reptiles and birds of the air. And a voice said to me, ‘Rise, Peter; kill and eat.’ But I said, ‘By no means, Lord; for nothing common or unclean has ever entered my mouth.’ And the voice answered a second time, ‘What God has made clean, do not call common.'”

He paused, letting the weight of those words settle in the quiet room. “This happened three times, and then it was all drawn up again into heaven.”

He told them then of the men from Caesarea, how the Spirit had told him to go with them without hesitation. He described the journey, the house of Cornelius, the crowd of relatives and close friends gathered there.

“And as I began to speak,” Peter continued, his eyes distant, seeing it all again, “the Holy Spirit fell on them, just as on us at the beginning. And I remembered the word of the Lord, how he said, ‘John baptized with water, but you will be baptized with the Holy Spirit.’ If then God gave the same gift to them as he gave to us when we believed in the Lord Jesus Christ, who was I that I could stand in God’s way?”

The room was utterly silent. The accusation had drained from their faces, replaced by a kind of stunned awe. The logic was inescapable. God’s actions had preceded their understanding. His grace had flowed beyond the banks of their tradition, and they could only watch its course and give thanks.

One of the elders, a man named Judah who had been most stern, slowly nodded his head. His shoulders relaxed. “Then to the Gentiles also,” he said, the words a quiet surrender, “God has granted repentance that leads to life.”

The tension broke. The story was told, and in the telling, it became part of them too. It was no longer just Peter’s strange encounter; it was the church’s new reality. A door had been opened that no one could shut. And outside, in the streets of Jerusalem and beyond, in the great wide world of the Gentiles, a wind was blowing, and it smelled of rain after a long drought.