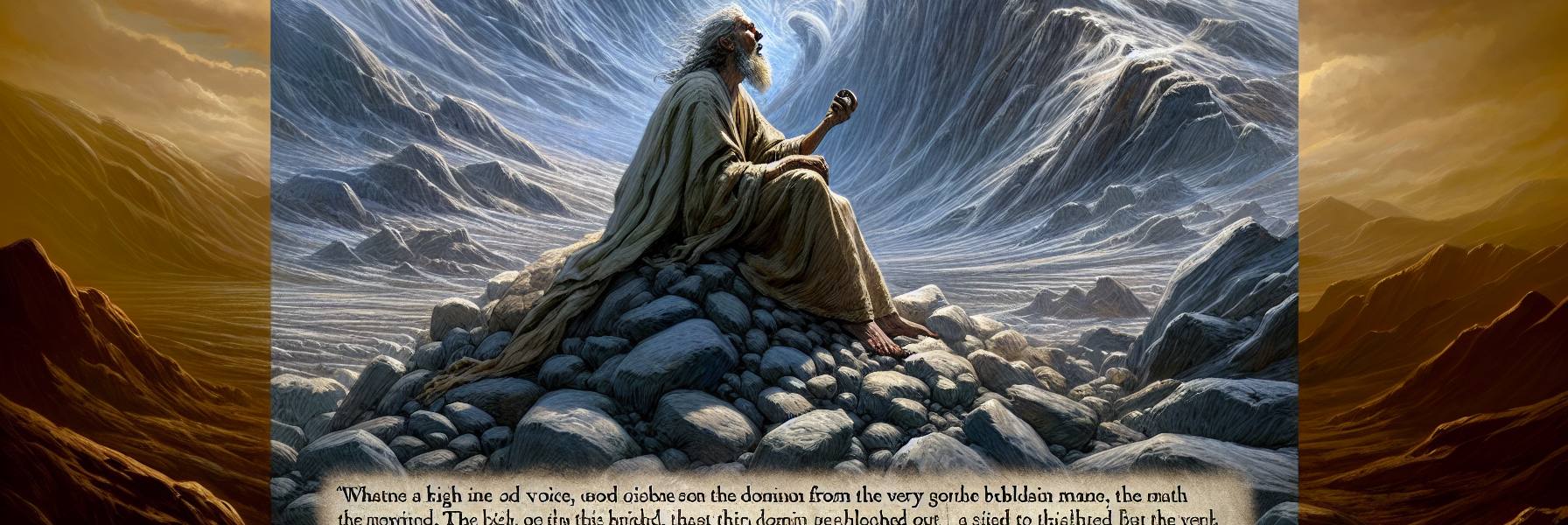

The air was thin and tasted of stone. Job sat on his ash-heap, not as a penitent now, but as a man hollowed out, a vessel waiting to be filled or shattered. The whirlwind had passed, leaving not silence, but a presence so vast it pressed upon the ringing in his ears. The voice, when it came again, did not boom from the clouds. It seemed to rise from the very rock beneath him, from the deep places of the earth.

“Now,” the voice said, and the word was like a key turning in a lock. “Will you instruct me in my own household? Will you oversee the shifts and duties of my world?”

Job said nothing. His chin, resting on his knees, felt like granite.

“Tell me, then, of the mountain goat. Do you know the hour of her birthing? Can you number the months she carries her young, there on the sheer rock-face where no man’s foot can find purchase? You, who have counted your own losses. Can you count the days of her hidden labor, when she crouches in the cleft, her sides heaving, and brings forth her kid in a spray of pebbles and defiance? She turns her back on the valleys, on the soft grasses. Her young grow strong on wind and vertigo, and they do not return to the dwellings of men. Who set her on that path? Who made her heart to love the precipice?”

A picture burned itself into Job’s mind: not a sentimental sketch of a creature, but the raw, muscular effort of a nanny goat, her hooves like forged iron, gripping a seam of quartz on a cliff face. He saw the kid, wobbling on impossible stilts, learning the world as a vertical plane. He had never considered their joy. Only their inaccessibility.

The voice continued, its tone shifting like landscape. “Who set the wild donkey free? Did you loose his bonds? I gave him the salt-flats for his home, the barren hills for his domain. He scorns the tumult of the city; he hears no driver’s shout. The range of the mountains is his pasture, and he searches out every green thing, not because you planted it, but because I hid it there for him to find. He is not your servant. His strength is his own, and his liberty is my gift to him. Do you grudge him his freedom, Job? Would you have him in your stable, dull-eyed and obedient?”

Job felt a strange, unwelcome envy. He saw the onager, dust-coated and sinewy, head thrown back to taste a distant rain on the wind. It was a creature of pure want, answering to nothing but its own hunger and the vast, open scripture of the wilderness. Its freedom was a rebuke to his own captivity, not to his flesh, but to his understanding.

Then, a new energy entered the voice, a rhythmic, pounding cadence. “Do you give the warhorse his might? Do you clothe his neck with thunder? Can you make him leap like the locust? His proud snorting is terror. He paws in the valley, exulting in strength; he goes out to meet the weapons. He laughs at fear, unshaken; he does not turn from the sword. The quiver rattles against him, the flashing spear and javelin. With fierceness and rage he swallows the ground; he cannot stand still at the sound of the trumpet. When the trumpet blasts, he says, ‘Aha!’ He smells the battle from afar, the thunder of captains and the shouting.”

This was no longer a question of management, but of essence. Job was not being asked to breed the horse, but to conjure its spirit. He could almost feel the seismic tremor of its hooves, see the foam flying from its bit, the flaring nostrils drinking the acrid scent of conflict. The animal’s courage was an absolute, a fierce glory poured into its form. It did not fight for a cause, but for the sheer, terrible joy of its own power, a power loaned to it for that very purpose. Job had known fear, known trembling. He had never known this.

The voice softened, turned its attention upward. “Is it by your wisdom that the hawk soars, spreading his wings toward the south? Does the eagle mount up at your command and make his nest on high? On the rock he dwells and lodges, on the crag of the rock, an inaccessible stronghold. From there he spies out food; his eyes see it from far away. His young ones suck up blood; and where the slain are, there he is.”

The vision lifted from the pounding earth to the patient, circling zenith. The hawk’s flight was a silent argument against petty striving. The eagle, a sovereign in its high place, saw the shudder of a dying hare from a distance that reduced men to specks. Its nest was a fortress in the sky; its provisioning was death itself, observed with a dispassionate, glorious eye. This was not cruelty. It was a complete, self-contained system of majesty and necessity, operating on a scale that made human morality seem a parochial concern.

The words ceased. The questions hung in the air, not as accusations, but as vast, unanswerable realities. Job had demanded a courtroom. He had been given a tour of the cosmos. He had sought an explanation for his suffering. He had been shown a wild donkey’s liberty, a warhorse’s ecstatic courage, an eagle’s pitiless domain.

He did not find answers in the sense of solved equations. He found a world drenched in a wild, untamable, and terrifying beauty—a beauty that did not exclude his pain, but utterly surrounded and dwarfed it. The Lord’s government was not about administering justice as Job understood it, but about presiding over a breathtaking, often savage, and profoundly free creation. His own story, for all its searing pain, was but a single thread in a tapestry woven with threads of thunderous hooves, soaring pinions, and the lonely cry of a goat on a cliff.

Slowly, very slowly, Job brought his hands up from the ash. He looked at them, no longer clenched in fists, but open. The silence now was not empty, but full. It was the silence of the rock holding the eagle’s nest, of the high plateau after the wild donkey has passed, of the battlefield in the strange, still moment before the charge. And into that silence, Job began to speak, his voice a rasp against the immense quiet, the first words of his long surrender.