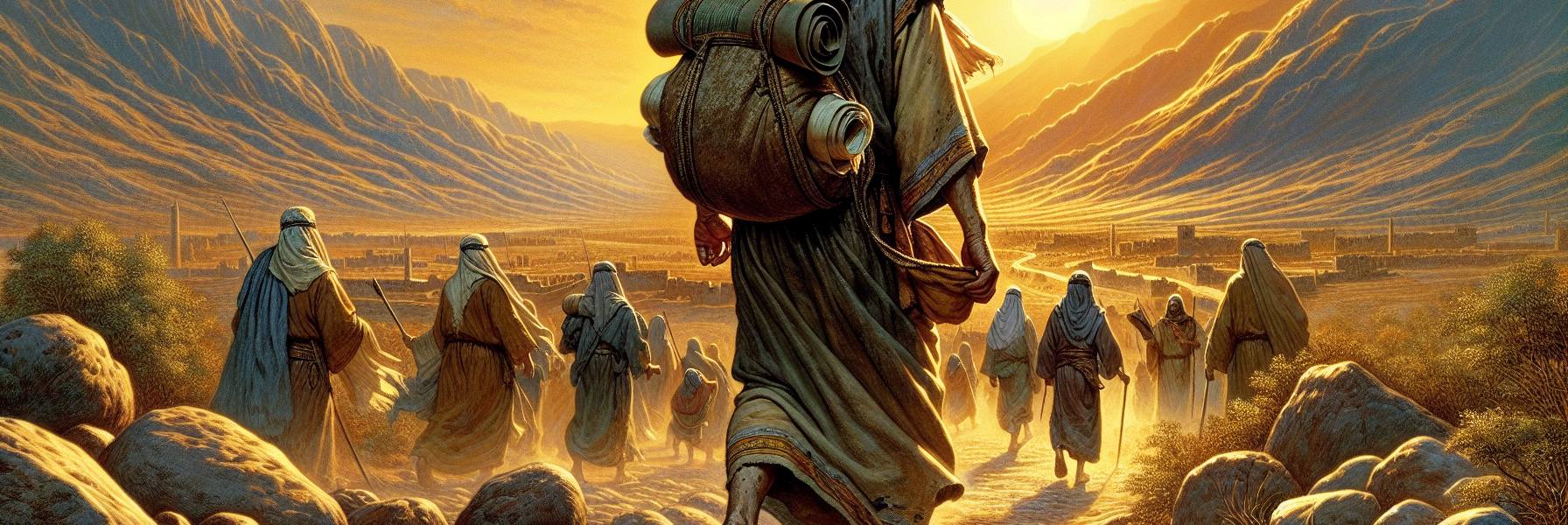

The sun was a hammer on the back of his neck. Ezra felt its weight with each step up the dusty incline toward Jerusalem, the grit of the road coating his sandals, his robes, the very scrolls he carried. He’d walked for months, this remnant of a return, a caravan of hope and temple gold. But the joy of arrival had been a shallow well, drunk dry in a single afternoon.

Now, the news sat in his gut like a stone.

He heard it first not as a formal report, but in the fragmented whispers that swirled in the newly restored courtyards. A Levite, his face ashen, had pulled him aside near the Water Gate. The words were hesitant, syrup-slow with shame. *They have not separated themselves… the people of Israel, the priests, the Levites… they are mingling with the peoples of the lands… the Canaanite, the Hittite, the Perizzite…*

Ezra’s mind, usually so ordered, a library of covenant law, fractured. He saw not just names from a scroll, but the groves on the high places, the small idols in the alcoves, the slow, patient poison of compromise. It wasn’t merely marriage. It was a unraveling of the very thread that held them together, the thread that had brought them back from the pit of Babylon.

He didn’t go to his quarters. Instead, his feet carried him, heavy as millstones, through the uneven streets, past houses built with borrowed stone on old foundations. He saw a child playing in a doorway, her features subtly different, a curl to the hair that spoke of Ammon. He saw a merchant laughing with a man whose accent was from Ashdod. Each glance was a needle-prick.

He found himself at the open space before the temple mount, the new altar standing bare in the late light. The work had stopped for the day. Silence hung over the stones, a more profound accusation than any noise.

Then it came, the physical wave of it. It started in his chest, a heat that was neither of the sun nor of anger, but of a terrible, rending sorrow. It was as if the stone in his gut melted and flooded his limbs. His hands, the hands that handled the sacred law, rose of their own volition. He tore his robe, a long, ragged sound that seemed to echo off the silent walls. Then he seized the mantle of his tunic and pulled, hearing the linen rip at the shoulder. He fell to his knees, then further, his forehead pressing into the cool, powdery dust of the ground. He pulled at his hair, the dark strands coarse between his fingers, and the beard he had kept trimmed for dignity.

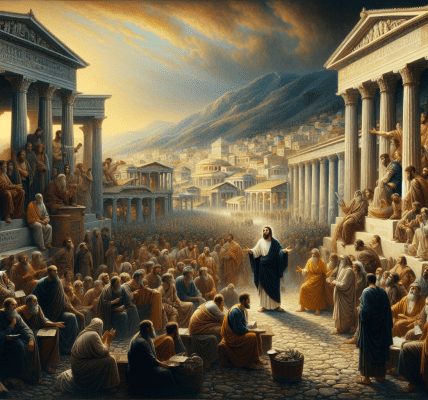

He stayed there, a heap of torn cloth and despair, as the shadows lengthened. A few passersby hurried past, eyes averted. Others stopped, their whispers turning to a low murmur of alarm. They knew the signs. This was not the posture of petition, but of calamity.

The crowd grew—a clot of anxious men, those who still trembled at the words of God. They stood at a distance, a semi-circle of fearful respect. The chill of evening began to seep from the earth, but Ezra felt only the inner fire.

At the time of the evening offering, when the smoke of the lamb should have been a sweet savor, he stirred. He pushed himself up to his knees, his robes hanging from him in ruins. He spread his hands, palms up, as if balancing the weight of the unseen.

His voice, when it came, was cracked from the dust and disuse. It did not boom. It scraped.

“My God… my God, I am ashamed. I am humiliated to lift my face to you.”

He swallowed, the sound thick in the quiet.

“Our iniquities. They rise higher than our heads. Our guilt has grown up to the heavens. From the days of our fathers… until now, we have been deep in guilt.” He spoke not as an orator, but as a man recounting a relentless, familial disease. “Because of our sins, we, our kings, our priests, were given into the hand of foreign kings. To the sword, to captivity, to plunder, to utter shame, as it is this day.”

He paused, his breath shuddering. A dog barked somewhere in the city, a lonely, domestic sound.

“And now, for a brief moment, grace has come from you… a remnant, a secure hold in your holy place. You have given us light to our eyes, a little reviving in our slavery. For we are slaves. Yet in our slavery, you have not forsaken us. You extended to us your steadfast love before the kings of Persia…”

Here his voice broke entirely. The kindness was the sharpest knife. He forced the words out, hoarse and stumbling.

“To give us a wall? A *wall* in Judah and Jerusalem? And now, O God, what can we say after this? For we have forsaken your commandments. The commandments you spoke through your servants the prophets…”

He listed them then, not as a recital, but with the weary dread of a man checking off a list of broken vows. The land defiled. The abominations. Taking foreign daughters for sons, mingling holy seed. The leaders and officials, the very ones who should have been the bulwark, leading in the treachery.

“Shall we break your commandments again and intermarry with the peoples who practice these abominations?” The question was not rhetorical. It was the desperate, logical end of a road they were walking. “Would you not be angry with us until you consumed us, until there was no remnant, no survivor?”

The sky had turned to deep violet. The first stars were cold, sharp points.

“O Lord, God of Israel, you are righteous. We are left this day as a remnant. Behold, we are before you in our guilt. None can stand before you because of this.”

He did not ask for forgiveness. He did not propose a solution. He simply stated the terrifying equation of their existence: a righteous God, and a people neck-deep in the very sin that had once broken them. The prayer ended not with a grand ‘amen,’ but faded into the settling dark, as if the words themselves were too heavy to remain in the air.

He stayed on his knees. The crowd did not disperse. They stood in the gathering night, shivering a little in the cool air, held there by the spectacle of a broken man and the dreadful, silent truth that his brokenness was their own. The story wasn’t over. It was, in fact, just beginning. But here, in the dust, with torn clothes and a raw throat, was the only place it could possibly start: not with a plan, but with a grief so profound it had to be God’s own.