The messenger, Tychicus, found the air of Ephesus difficult to breathe. It wasn’t the heat, though the late afternoon sun pressed down on the crowded streets like a flat, bronze hand. It wasn’t the thick, greasy smoke from the countless sacrifices at the Temple of Artemis, which hung in the harbor air like a perpetual twilight. It was the weight of the thing in his pack, a small, tightly-rolled scroll that felt heavier than stones.

He’d carried letters before, across mountain passes and pirate-haunted seas. But this one was different. It had come from the old man, John, on Patmos. A place of exile, of rocks and salt spray and visions. Tychicus had seen his face as he’d given it over—a face etched by time and something else, a terrible, beautiful clarity. “To the angel of the assembly in Ephesus,” John had said, his voice a dry rustle of papyrus and spirit.

Now, Tychicus stood before the meeting place, a nondescript house in the shadow of the great theatre. He could hear the murmur of voices from within, a sound both familiar and, tonight, strangely fraught. He pushed the door open.

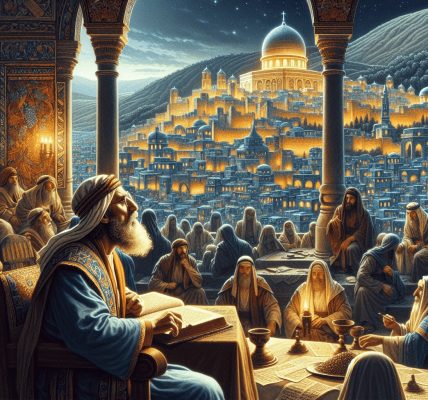

The room was a tapestry of shadows and lamplight. Faces he knew, men and women whose hands were calloused from labor, whose eyes were weary from the daily strain of living as a foreign sect in a city drunk on goddess-worship and commerce. There was old Linus, his back bent from tent-making; Prisca, her gaze sharp as a scribe’s; and the younger ones, their faith still bright but untested by decades of vigilance.

They gathered around him, the dust of the day still on their tunics. No one spoke. The air of Ephesus had followed him in—that pressure, that waiting. Tychicus untied the leather pouch and drew out the scroll. He didn’t need to read it; the words were burned into him from the journey, a fire in his memory. He began to speak, not in his own voice, but as a conduit for the one who walks among the lampstands.

“Write this,” he said, and the room grew stiller. “To the messenger of the assembly in Ephesus: Thus says the one who holds the seven stars in his right hand, who walks in the midst of the seven golden lampstands…”

A collective breath was drawn. The imagery was from their own shared mystery, the vision of their Lord holding the churches like stars, walking among them as lights in the world. It was a comfort, and a profound accountability.

“I know your works,” the voice through Tychicus continued, and there was a nodding, a faint straightening of spines. They had works. Oh, they had works. Tychicus saw the lines of endurance on their faces. “Your toil and your patient endurance, and that you cannot bear evil men.” Here, a few glanced at the door, as if remembering the slick philosophers from the Agora, or the zealous devotees of the Emperor, or the sly Gnostics with their secret knowledge, all of whom they had tested and found false. “You have tested those who call themselves apostles and are not, and found them to be liars. You have endured patiently for my name’s sake, and have not grown weary.”

It was a true record. Ephesus was a fortress of orthodoxy, a bastion against the creeping heresies that plagued other assemblies. Their doctrinal purity was impeccable, a razor’s edge. They could spot a theological error at a hundred paces. A murmur of grim satisfaction rippled through the room.

Then came the pause. Not from Tychicus, but from the spirit of the words themselves, a silence that stretched like a chasm in the middle of the pronouncement.

“But I have this against you…”

The satisfied murmur died. The air left the room.

“You have abandoned the love you had at first.”

The sentence fell like a stone into a deep well. No one moved. Tychicus watched the words land on each face. On Linus, who had once wept with joy at his baptism in the Cayster River, but now argued more fiercely about the nature of the Christ than he embraced his brothers. On Prisca, whose brilliant defenses of the faith sometimes carried a sharper edge than the gospel of peace. On the young ones, who had learned to critique before they learned to cherish.

First love. It wasn’t a doctrine. It wasn’t a work of endurance. It was a memory, almost painful in its sweetness. It was the reckless joy of forgiveness when they first believed. The unguarded fellowship of shared meals, where the talk was of Jesus, not of Judaizers. The prayers that were more like laughter, the generosity that didn’t first calculate orthodoxy. It was the flame at the center of the lampstand, which now seemed surrounded by impeccable, cold, polished gold.

“Remember therefore from where you have fallen,” the voice urged, not with a shout, but with the terrible tenderness of a surgeon’s knife. “Repent, and do the works you did at first.”

Repent. The word hung there. They thought repentance was for sinners, for idolaters. Now it was for them, the vigilant, the doctrinally sound. The hardest repentance of all.

The message didn’t end with the wound. It offered the salve, and the terrible alternative. “To the one who conquers, I will grant to eat of the tree of life, which is in the paradise of God.” The paradise lost, restored. A promise that tasted of home.

But first, the warning: “If not, I will come to you and remove your lampstand from its place.”

The silence that followed was absolute. It wasn’t the silence of shock, but of a deep, communal hearing. The removal of the lampstand. It wouldn’t be a persecution from without. It would be a quiet, spiritual extinction. The light would simply go out. Ephesus would remain, bustling, pagan, prosperous, and the memory of the assembly would become a footnote, its beautiful, correct doctrines like notes of music played in an empty hall.

Tychicus finished. The scroll felt light now, the weight transferred to the hearts in the room. He rolled it up. No one rushed to speak. There were no debates about Greek participles, no dissections of the Nicolaitan heresy mentioned later in the letter. Those things, for this moment, seemed like distant noise.

Old Linus was the first to move. He didn’t speak. He simply stood, walked slowly to his brother Marcus, a man he’d debated fiercely the week before over a point of prophecy, and put a gnarled hand on his shoulder. Marcus looked up, and his eyes, usually so full of argument, were bright with something else. Something older.

One by one, lamps were lit as the true dark of the Ephesian night descended. But in that room, another kind of kindling was happening, hesitant and fragile. A rekindling. The letter had done its work. It had not commended them for their strength, but had found them in their hidden weakness. It had not offered a new teaching, but had called them back to an old, simple, terrifying one: to love as they were first loved.

The messenger sat down, his task complete. The words were no longer his. They were now in the care of the assembly, to heed or to ignore, to let them be a mirror or a relic. Outside, the city of Ephesus carried on, oblivious. But inside the house, under the watchful eye of the one who walks among the lampstands, a long-forgotten fire was being gently, carefully, fanned back to life.