The air in Jerusalem held the peculiar stillness of a kingdom holding its breath. Josiah was eight years old when they placed the crown upon his head, a weight of gold and expectation he could scarcely comprehend. The stones of the palace felt cold under his small sandals. He remembered the whispers, the sidelong glances at his father Amon, a man whose memory was a stain of foreign altars and silent, sanctioned idols. The boy-king grew in the shadow of those whispers, and in his sixteenth year, a fire kindled in him—not yet a blaze, but a quiet, stubborn ember of seeking.

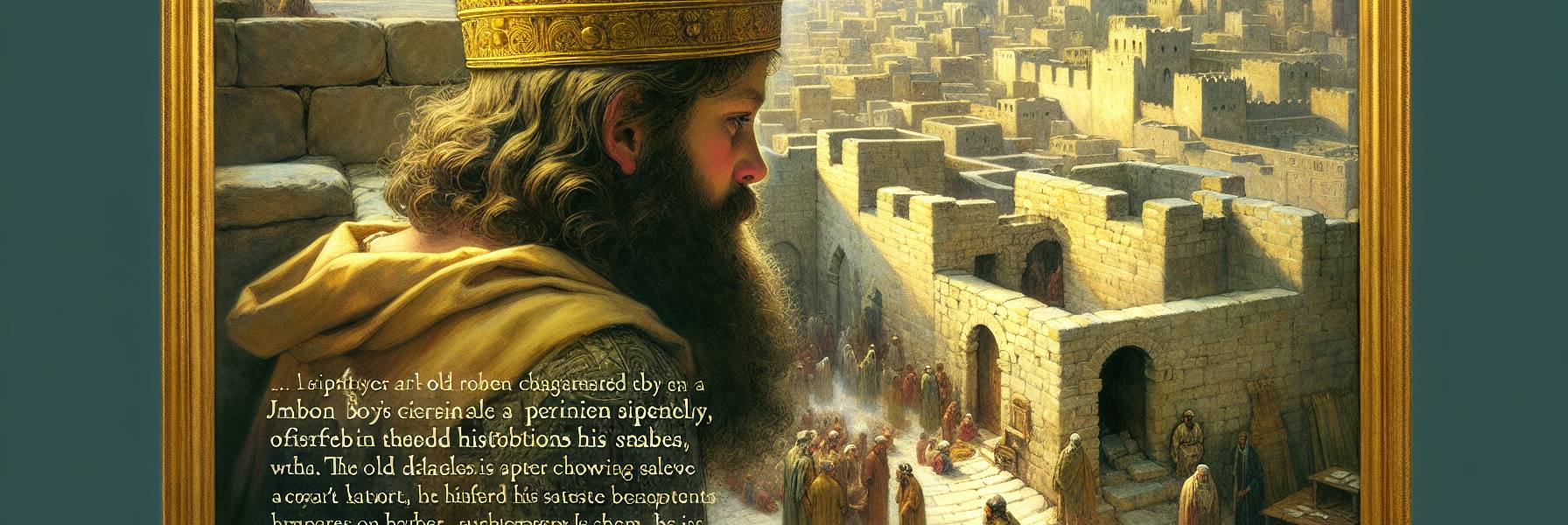

It began, as such things often do, in private. Before he ever issued a decree, he sought out the old scrolls, the fragmented histories kept by aging priests in back chambers. He walked the hills of Judah alone, looking at the high places his grandfather Manasseh had built, seeing not monuments of devotion but wounds upon the land. In his twentieth year, the ember became a flame. He ordered the cleansing of Jerusalem. It was not a distant, regal command; Josiah went out himself, his cloak dusty, his hands calloused from helping to topple the Asherah poles. He watched as the carved images were ground into powder, the pagan altars broken into jagged teeth of stone. The work was physical, gritty, and left the taste of limestone and old incense in his throat.

But Jerusalem was only the beginning. The rot had spread. So he went north, into the territories of what had been Israel—Bethuel, Simeon, Naphtali—lands long conquered by Assyria and left spiritually desolate. Here, the idolatry was older, more entrenched. In the ruins of Bethel, he stood before the altar Jeroboam had built centuries before. The local elders watched, faces unreadable, as Josiah’s men dismantled it stone by cursed stone. He had the tombs of the false priests opened and their bones burned upon the ruined altar, a final, stark defilement to break the chain of memory. It was brutal, practical work, a surgery upon the land. He did not feel triumphant, only weary and determined, the grit of ancient mortar permanently under his nails.

After years of this itinerant purification, he returned to Jerusalem. The Temple, the physical heart of it all, needed restoration. It had been neglected, its timbers rotted, its gold leaf peeling. He appointed scribes and overseers—Shaphan, Maaseiah, Joah—men of trustworthy hands. They collected the silver from the people, a humble, hopeful tax for repair. One afternoon, in the eighteenth year of his reign, the high priest Hilkiah sent word to the palace. There was more than repaired stonework to report.

Shaphan the secretary came, his face pale beneath his beard. In his hands was a scroll, its leather brittle, its edges frayed. “Hilkiah the priest has given me a book,” he said, his voice oddly formal, a tone one uses to speak of things too large for ordinary words. He read from it aloud in the king’s chamber. The words were ancient, the rhythms of Moses, but their meaning was horrifyingly immediate. It spoke of a covenant broken, of blessings forfeited, and of a wrath so fierce it would make the ears of whoever heard it tingle.

Josiah did not just listen; he was unraveled by it. He tore his robes, a raw, violent gesture of grief. The reforms, the relentless work, the toppled idols—it had all been obedience to a law he had never fully known. Now, hearing its terrible, beautiful contours, he understood the depth of the apostasy. The wrath described was not just for his fathers; it was for a people who had forgotten the very sound of their own story. “Go and inquire,” he commanded his servants, his voice thick. “Inquire of the Lord for me, and for those who are left in Israel and Judah, concerning the words of this book that has been found.”

They went to Huldah the prophetess, who lived in the newer quarter of the city. Her words were no comfort. Yes, the Lord had seen the king’s tenderness, his humility. He would be gathered to his grave in peace; his eyes would not see all the disaster. But the decree against Jerusalem and its people was fixed. Their forsaking had been too complete, their incense burned to too many other gods. The scroll was authentic, and its judgment stood.

Josiah received this bitter news with a solemn nod. If the end was certain, then the meantime would be one of radical fidelity. He gathered every elder, every citizen, from greatest to least, and read the entire book of the covenant to them in the Temple court. In that vast, silent crowd, under the wide Judean sky, he made a pledge himself, a vow to follow the Lord with everything in him. The people, stirred by his raw, kingly grief, joined him. For the rest of his days, they did not turn away.

He kept the Passover that year in a way no one living could remember. The chronicler would later write there had never been one like it, not since the days of Samuel. The king provided thirty thousand lambs and young goats from his own flocks. The priests stood in their divisions, the Levites taught the people the old songs, and the doors were flung open. For a brief season, Jerusalem was what it was meant to be: a city remembering its name. Josiah stood among them, not as a distant monarch, but as a penitent, a steward of a dying flame.

Years later, he went out to meet Pharaoh Neco at Megiddo, a political maneuver to intercept an empire’s march. It was not his war. The Egyptian archers found their mark, and Josiah was carried, wounded, from his chariot. He died in Jerusalem, and all Judah and Jerusalem mourned, a genuine, piercing grief for the king who had tried to give them back their soul. They buried him among his fathers. The prophet Jeremiah sang a lament for him, and the singing men and women still speak of Josiah in their laments to this day. The disaster he feared did indeed come, sweeping away the Temple and the city. But the memory of that eighteenth year, of the dust falling from a lost book and a king tearing his clothes in love and terror, remained—a fragile, human testament to the power of a truth, however late it is found.