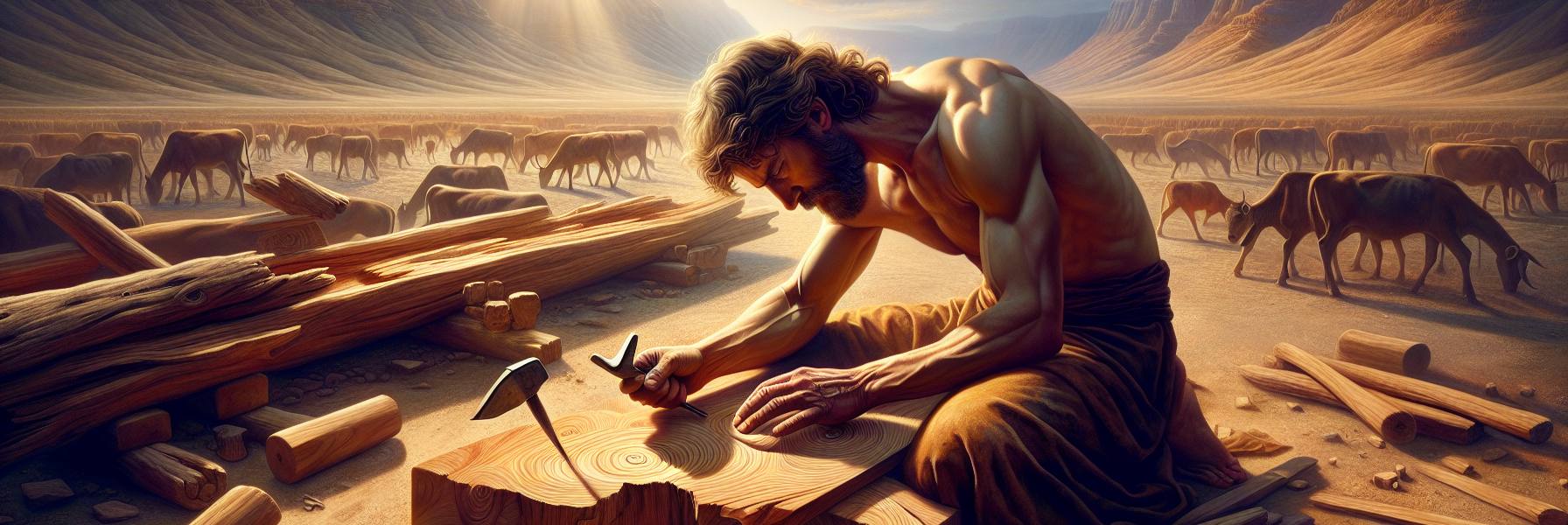

The heat of the sun was a physical weight on the back of Bezalel’s neck as he crouched in the dust. His fingers, calloused and stained, traced the whorls of a piece of acacia wood, his mind seeing not the rough branch but the smooth curve of an ark’s leg. Around him, the immense silence of the wilderness was broken only by the distant lowing of cattle and the murmur of a vast, restless people. He was a man accustomed to the language of materials—the whisper of grain in wood, the stubborn resistance of flint, the sleepy malleability of heated gold. The grand visions Moses described, the tent of meeting, felt like dreams blown on the wind. Beautiful, impossible dreams.

He didn’t hear Moses approach. A shadow fell across his work, and he looked up, squinting. The prophet’s face was changed, not just wearied by the mountain, but illuminated from within by some solemn, consuming fire. “Bezalel, son of Uri, son of Hur,” Moses said, and his voice, though quiet, carried a strange, formal gravity that made the craftsman rise to his feet, dusting his hands on his tunic.

“My lord?”

“The Lord has spoken by name.” The words hung in the hot air. “Not to the priests, not only to the leaders. To you.”

Bezalel felt a cold ripple up his spine, despite the heat. God knew names. He knew Abraham, Isaac, Jacob. He knew Moses. The names of craftsmen were written in workshop tallies, not in the councils of heaven.

Moses stepped closer, his eyes holding Bezalel’s. “See, I have called you by name. I have filled you with the Spirit of God, with ability and intelligence, with knowledge and all craftsmanship.”

The words were like a hammer blow to his chest, not of fear, but of profound, terrifying recognition. That inner sight, that sudden knowing of how a joint should fit, where a gem should sit—he had always thought it just a keen eye, a patient hand. Now it was named. It was *Spirit*. The very breath of God was the source of the ideas that flickered behind his eyes when he stared at a raw stone. The understanding flooded him, warm and immense, a tide of purpose that washed away the dust of impossibility.

Moses was still speaking, listing the works: the ark and its table, the lampstand of pure gold, the altars, the anointing oil, the fragrant incense. The list was a blueprint sung into existence. “And to work in every craft,” Moses finished. Then he gestured, and Oholiab, the wiry, precise weaver from the tribe of Dan, stepped forward, his own face a mask of awestruck understanding. “I have appointed him with you, and I have given to all able men ability, that they may make all that I have commanded you.”

The next days were not a frenzy, but a kind of sacred, ordered awakening. Bezalel and Oholiab moved through the camp, and their seeing was different now. They saw not just men, but hands. The steady, patient hands of a woodcarver named Eliah, who could make acacia wood sing. The impossibly fine, swift fingers of Miriam, not the prophetess, but a younger woman who could spin goat’s hair into thread as soft as cloud. They saw the fierce concentration of a metalsmith named Helez, whose forge would soon breathe life into bronze.

They gathered them, these men and women filled with the *wisdom of heart*. There was no single great announcement, just a slow gathering by the new workshop grounds, a quiet sharing of the vision. Bezalel found he did not need to command; he needed only to describe what he saw with his Spirit-touched inner eye, and the others would nod, their own understanding kindling. “The cherubim,” he would say, staring at a blank sheet of gold, “their wings will be like… a storm’s shelter. Not just covering, but active, held in a moment of perpetual reverence.” And the metalworkers would murmur, seeing it too.

The work began. It was work. Sweat dripped into eyes, thumbs were struck with hammers, a carefully carved piece would split along a hidden grain and a groan would go up. But under it all thrummed a current of divine certainty. The tabernacle was not being invented; it was being remembered, unearthed from the mind of God and given substance by human hands blessed for the task.

One evening, as the sun bled over the horizon, Moses came again. The workers had ceased, bodies aching but spirits quiet. Moses looked at the beginnings—the frames leaning together, the first shimmering plates of gold, the bolts of linen waiting for Oholiab’s looms. His gaze was solemn.

“But you,” he said, his voice rolling over the weary, contented craftsmen, “you shall keep my Sabbaths. It is a sign forever. For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, and on the seventh day he rested and was refreshed.”

The words landed with perfect, resonant clarity. Bezalel understood. This creative fury, this divine skill pulsing through them, was a reflection of the Creator’s work. And as He had rested, so must they. The Sabbath would be the seal upon their labor, the weekly reminder that the skill was a gift, the work a calling, and the God who dwelt in unapproachable light was the same God who would soon dwell among them, in a tent built by gifted, obedient, resting hands.

Bezalel looked at his own hands, scarred and capable. They were his, yet not his alone. He nodded, not just to Moses, but to the deepening twilight, to the rhythm of creation itself. The work would resume. And then, it would rightly, necessarily, stop. And in that stillness, they would be most like the God they served.