The memory of the winepress haunted Malachi’s old age. Not the neat stone troughs of his uncle’s vineyard outside Anathoth, where the grapes yielded their sweetness with a sigh. No, this was a different kind of pressing. He saw it when he closed his eyes, in the quiet hours before dawn when Jerusalem’s stones held their breath.

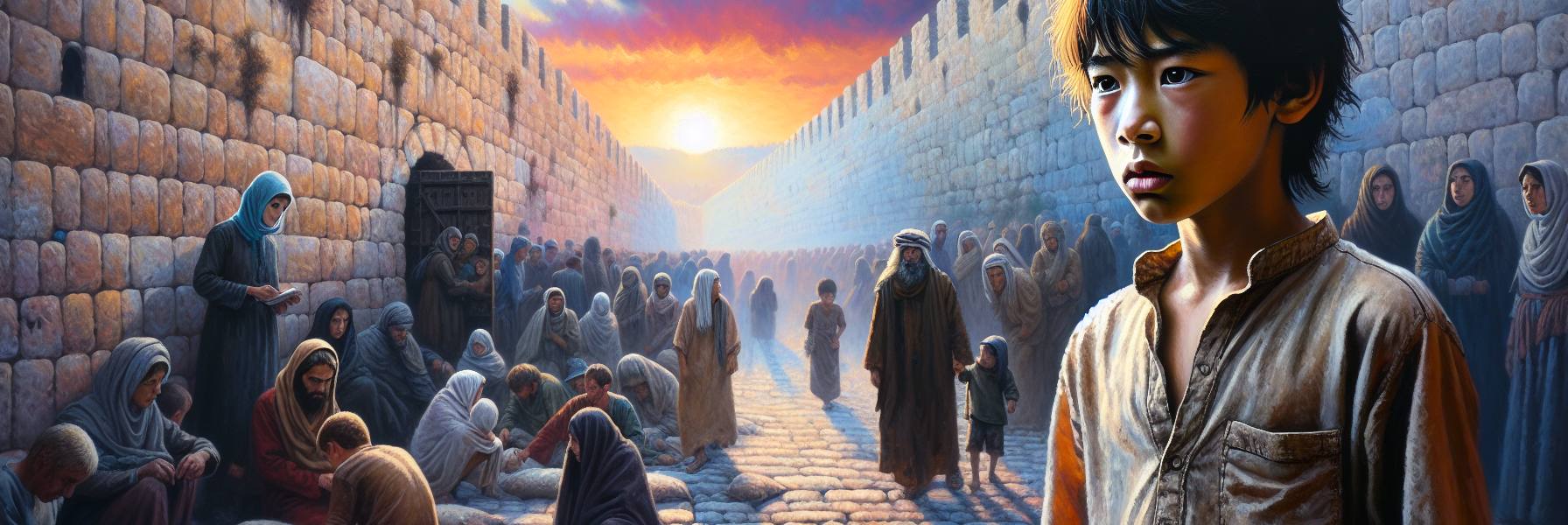

He was a boy of nine when the prophet’s words first fell on the assembly, heavy as summer thunder. The man’s name was lost to him now, a itinerant voice from the wilderness of Judah, skin like cured leather and eyes that held the harsh glint of the eastern desert. He stood in the shadow of the cracked city wall, where the refugees from the north huddled, and he spoke of a day not yet come.

“Who is this who comes from Edom,” the prophet cried, his voice rasping against the silence, “in garments stained crimson from Bozrah?”

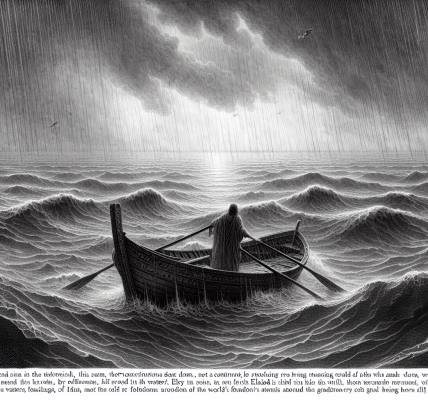

Malachi, clinging to his father’s woolen cloak, saw it. Not with his eyes, but somewhere deeper. A figure, solitary, moving with the terrible, deliberate pace of a harvest master at the end of a long season. The land around him was not the green hills of Judah, but the red, rocky heights of Edom, their ancient enemy, gloating in its barren security.

“I have trodden the winepress alone,” the voice continued, and Malachi felt a chill unrelated to the evening breeze. “From the nations, no one was with me.”

The description unspooled, vivid and terrifying. It was not grapes that stained the robes, but the life-blood of wrath, a judgment so complete it splattered the garments like the juice of a pomegranate shattered underfoot. The prophet spoke of a day of vengeance, a year of redemption for Zion. The warrior’s arm brought salvation, his own righteousness sustained him. His fury was a slow, inexorable press, a divine necessity.

The boy Malachi did not understand the fullness of it. He only felt the awe, and a fearful thrill that the wrongs done to his people—the taunts of Edom, the arrogance of all the nations—would not stand forever. There was a righteousness that would wear crimson-stained robes.

***

Decades passed. The memory faded to a colored thread in the tapestry of his life, woven alongside the fall of Jerusalem, the exile, the dusty, heart-sore return. Malachi was an old man now, his own eyes holding the gloss of polished stone, his hands gnarled like the roots of the few olives that had survived the Babylonian axes. He sat with the younger men by the rebuilt gate, the one they called the Sheep Gate, though the flocks were pitifully small.

They asked him of the former days, of the prophets. Their faith was a fragile thing, like the new mortar between the stones, constantly needing repair. Where was the glory? Where was the vengeance?

And the old memory of the winepress returned, but it was no longer solitary. Another scripture, from the same scroll of Isaiah, echoed up from the depths of his spirit, merging with the first. He cleared his throat, the sound like dry leaves.

“You remember the warrior,” he said, his voice low. “The one in red, from Bozrah. We thought… we thought that was the end of the story. The victory. The settled score.”

He paused, his gaze drifting over the meager city, the struggling people. “But the prophet… he saw further. He saw what comes after the vengeance. Or rather, *who* comes after.”

He began to speak again, but the tone was utterly changed. No longer the thunder of the divine warrior, but the aching, bewildered cry of a child.

“I will tell of the kindnesses of the Lord,” Malachi murmured, but the words quickly curdled into a lament. “He said, ‘Surely they are my people, children who will not be false.’ So he became their Savior.”

The old man’s eyes grew moist. “In all their distress, he too was distressed. Not a distant judge. Not a wrathful stranger. He was the angel of his own presence who saved them. In his love and mercy, he redeemed them. He lifted them up and carried them all the days of old.”

A long silence hung in the air, thick with the dust of the street. The younger men leaned in, confused. This was not the triumphant story they expected.

“But then,” Malachi whispered, the pain of centuries in his breath. “But then we… we rebelled. We grieved his Holy Spirit.” He looked at his own hands, as if seeing the guilt there. “So he turned, became our enemy. He himself fought against us.”

Now the narrative turned inwards, into a dark cellar of memory. The warrior from Edom was no longer a distant avenger; he was the very God they had spurned. And his absence was a deeper wound than any sword could make.

“Where is he?” Malachi cried out, giving voice to the ancient, collective groan. “Where is he who set his holy power among them? Where is he who divided the waters before them? Who brought them through the depths, like a horse in open country, so they did not stumble? The Spirit of the Lord gave them rest.”

The questions hung, unanswered. The winepress of Edom was a promise of justice, yes. But this—this was the story of a broken heart. The heart of God. The divine pathos. The love that chooses, carries, is betrayed, and yet, the prophet hinted, does not let go.

Malachi fell silent, exhausted. The sun was low, casting long shadows. The story was not a simple tale of good triumphing over evil. It was a marriage of terrifying holiness and heartbreaking mercy. The same one who treads the winepress of the nations is the same one who carries his wayward children on the crook of his arm.

“We must wait,” the old man finally said, his voice a bare whisper. “Not just for the warrior. But for the father. The one whose garments are stained with more than the blood of grapes.”

The young men left quietly, the easy clarity of vengeance replaced by the harder, more profound mystery of a love that judges *and* redeems. And Malachi sat still as the twilight bleached the color from the stones, holding in his heart the two visions together: the solitary figure in crimson from Bozrah, and the echoing, unanswered cry of a people for the God who had once carried them. The story was unfinished. It demanded a longer obedience, a deeper repentance, a hope that clung not to power, but to the character of the one whose ways were as much marked by the dust of the road where he carried his children, as by the red wine of his justice.