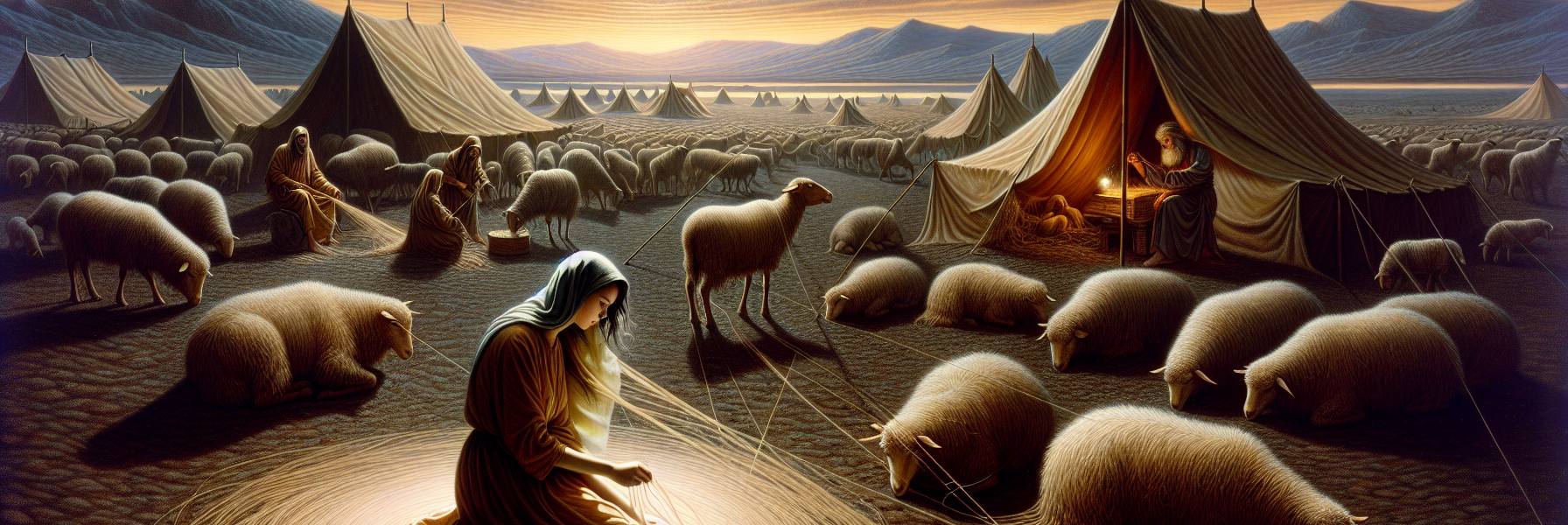

The years in Canaan had settled into a rhythm of dust and promise. The sun, a constant bronze coin in the vast sky, beat down on the flocks Abram tended, and on the quiet, spacious tents of his household. Inside one such tent, Sarai sat perfectly still, the only movement the slow twist of flax between her fingers. The silence around her was not peaceful; it was heavy, a wool blanket smothering hope. Every rustle of the tent flap, every distant bleat of a lamb, was a reminder of what the silence did *not* contain: the cry of a child, her child.

The promise Yahweh had made to Abram echoed in her mind, a beautiful, tormenting melody. *Heir. Descendants. Numberless as the stars.* And yet her own body, month after aching month, year after relentless year, remained a sealed tomb. The promise felt like a magnificent garment displayed before a beggar, beautiful to behold but impossible to wear. She watched Abram, her lord, his face etched with a faith that seemed, to her, to border on a kind of tranquil madness. He believed. He simply *believed*. Her own faith had worn thin, ground down by the gritty reality of empty arms.

Her eyes fell upon Hagar, the Egyptian maid, moving with a youthful, unconscious grace as she prepared a basket of bread. Hagar’s hands were strong, her body vibrant with a life that seemed to hum just beneath the skin. A thought, which had begun as a whispered, shameful notion in the deep watches of the night, now solidified in the daylight. It was not a good thought, but it was a practical one. It was a way, the only way her desperate mind could conceive, to give the promise flesh.

That evening, after the meal, with the scent of roasted meat and woodsmoke lingering, Sarai spoke. Her voice was low, stripped of its usual music. “You see that Yahweh has kept me from bearing. I pray you, go in to my maid. It may be that I shall obtain children by her.” She did not look at him as she said it, her gaze fixed on the glowing heart of the fire. The words felt foreign, like stones in her mouth. It was the custom, of course. Other women did this. But speaking it aloud made the surrender real, a formal abdication of her own body’s purpose.

Abram listened. In his silence, Sarai heard not disapproval, but a weary acquiescence. He was a man caught between a divine voice and his wife’s tangible despair. The text says he heeded the voice of Sarai. He did not argue, did not remind her of the promise, did not counsel patience. Perhaps his own patience was fraying. Perhaps the sight of her sorrow was a heavier burden than theological uncertainty. So he went in to Hagar, and she conceived.

The change in the Egyptian woman was not subtle. It was as if the life growing within her amplified her very essence. The quiet, efficient servant began to fade, and in her place stood a woman aware of a profound and singular power. The flat, respectful glance she gave Sarai grew shallow, then tinged with something else—a pitying pride. Every gentle swell of her belly was a silent indictment. Sarai, the mistress, was barren. Hagar, the maid, was life-bearer. The hierarchy of the tents, once clear as the desert sky, grew murky and hot with unspoken words.

Sarai’s desperation curdled into a sharp, white-hot bitterness. The plan she had crafted, the sacrifice she had made, now tasted of ash. She had sought to build through Hagar, but instead felt herself being dismantled. She turned to Abram, her composure shattered. “This wrong done to me is your fault! I gave my maid to your embrace, and now that she sees she has conceived, I am diminished in her eyes. May Yahweh judge between you and me!”

Abram, faced with this storm of female anguish, reverted to the boundaries of custom. His reply was almost helpless. “Your maid is in your hand. Do to her what seems good to you.” It was a restitution of authority, but it was cold comfort. He handed Sarai back the reins of a situation already careening into the wilderness.

And Sarai was not gentle. The weight of her disappointment, her jealousy, her public shame, she poured out onto Hagar. The text says she dealt harshly with her. The words suggest a pressure, a wearing down—sharp tongues, heavier tasks, a relentless reminder of her place. The proud glint in Hagar’s eye soon fractured into fear. The tent that had been her shelter became a prison of scorn.

So one morning, before the sun had burned the dew from the grass, Hagar fled. She took nothing but a skin of water and the clothes she wore, turning her back on the tents of Abram, on the promise, on the mistress whose hope had turned to venom. She set her face toward the south, toward the wilderness of Shur, a trackless waste that lay between Canaan and her homeland of Egypt. She walked until the ache in her feet matched the one in her spirit, until the vast, indifferent emptiness of the desert mirrored the emptiness inside her.

She found a small, lonely spring, a mere dampness in the rocks, and sank down beside it. Here, in the middle of nowhere, the full weight of her solitude crashed upon her. A runaway slave, pregnant, alone. The child within her stirred, a flicker of life that now felt like an anchor. What future was there? To die of thirst under this sky? To be found by marauders?

It was then that the messenger of Yahweh found *her*. He did not appear in a blaze of light, but rather his presence seemed to coalesce from the shimmering heat-haze, becoming solid by the water’s edge. “Hagar, maid of Sarai,” he said, and his voice was not thunderous, but it carried a strange, penetrating clarity. “Where have you come from, and where are you going?”

The question undid her. It was an invitation to her own story. Her words tumbled out, a confession not of sin, but of circumstance. “I am fleeing from my mistress Sarai.”

The messenger did not condemn her flight. Nor did he send her back immediately with a simple command. Instead, he gave her a promise of her own. “Return to your mistress,” he said, “and submit to her hand.” It sounded like a sentence. But then he continued, “I will surely multiply your offspring so that they cannot be numbered for multitude.” He spoke of the son in her womb, instructing her to name him Ishmael—*God Hears*. “For Yahweh has listened to your affliction.” He described the boy’s future: a wild donkey of a man, his hand against everyone, everyone’s hand against him, dwelling apart from his brothers.

Hagar, an Egyptian slave-girl, had been seen. Not as a vessel, not as a problem, but as *Hagar*. The God of Abram had spoken to *her*, had named her son, had given her a future. A strange, fierce joy broke through her terror. She did not name Yahweh—that name belonged to Abram’s covenant. Instead, she gave a name to the One who spoke to her. “You are *El Roi*,” she whispered to the lingering presence, “the God who sees.” For she said, “Have I truly seen the One who sees me here, after he has seen me?” The spring where she sat became Beer-lahai-roi, “The Well of the Living One Who Sees Me.”

She rose, her limbs heavy but her spirit strangely light. The wilderness was no longer a place of desolation, but the very ground where she had been found. She turned and retraced her steps, back toward the tents of Abram, back to the harshness of Sarai. But she carried a secret now, a well of water within her. She returned, and in time, she bore Abram a son. Abram, eighty-six years old, named him Ishmael, just as the messenger had said. And Hagar would sometimes look at her wild, beloved boy, and remember the heat, the spring, and the voice that had seen her in the middle of nowhere, changing the story forever.