The dust of the road, fine as ground meal, rose in little puffs around their sandals. It was a road worn smooth by countless feet, a road that led, as all roads in Judea seemed to, toward Jerusalem. Jesus walked ahead, his stride purposeful, yet his face was set in a way that made the disciples hesitate to draw too near. There was a gravity to him these days, a weight they could feel but not name.

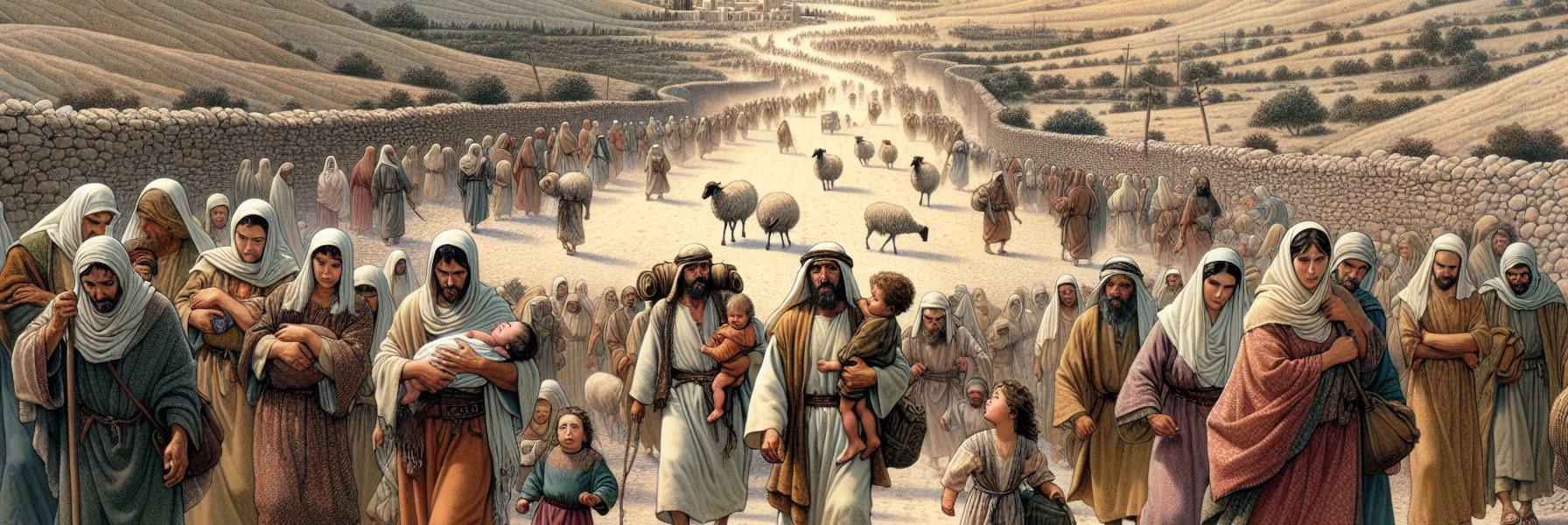

They passed through a stretch of country where the hills were dotted with sheep, and the air carried the distant, plaintive cries of children. It was then that they saw them—a cluster of people, mostly women, coming toward them with a quiet urgency. They held their children in their arms or had them by the hand, toddlers stumbling on the uneven path, infants swaddled against the sun. The disciples, weary and protective of their Teacher’s somber mood, moved to form a barrier. Peter, his voice a low rumble, began to speak. “The Master is tired. He has no time for babies.”

But Jesus heard. He stopped walking entirely and turned. The look on his face wasn’t one of anger, but of a profound, sorrowful disappointment that cut deeper than any rebuke. “Let the little children come to me,” he said, and his voice, though not loud, silenced the murmur of the crowd and the shuffling of the disciples’ feet. “Do not hinder them. For the kingdom of God belongs to such as these.” He knelt right there in the dust, the fine powder coating the hem of his robe. One by one, he took the children into his arms. He placed his hands on their small, warm heads, their hair smelling of sun and olive oil. He blessed them, not with a hurried formula, but with a quiet, specific tenderness that made the mothers weep silently. “Truly I tell you,” he said, looking up at his bewildered followers, “whoever does not receive the kingdom of God like a little child will never enter it.” It wasn’t about innocence, some of them grasped later. It was about the uncalculating trust, the complete dependence, of a child swept up into its father’s arms.

The encounter left a strange peace in its wake, but the road to Jerusalem waited. They hadn’t gone far when a man came running. He was young, his robes of fine linen, the fringe meticulously kept. He knelt in the dust before Jesus, an act of great respect. “Good Teacher,” he gasped, “what must I do to inherit eternal life?”

Jesus regarded him. “Why do you call me good? No one is good—except God alone.” The words hung in the air, a question wrapped in a statement. “You know the commandments: ‘You shall not murder, you shall not commit adultery, you shall not steal, you shall not give false testimony, you shall not defraud, honor your father and mother.’”

The young man’s face was earnest, unshadowed by doubt. “Teacher,” he said, “all these I have kept since I was a boy.”

And then came the look. Jesus looked at him—not at his fine clothes or his kneeling posture, but into him—and loved him. It was a look that saw the lonely mansion of his soul, every room in order, yet echoing with emptiness. “One thing you lack,” Jesus said, and his voice was gentle, the gentleness of a physician before a painful cure. “Go, sell everything you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me.”

The man’s face, so full of eager hope, collapsed. It didn’t fall suddenly, but slowly, like a wall settling into ruin. The light in his eyes guttered out. He looked down at the dust, now soiling the knees of his expensive robes. Without another word, he stood up and walked away, his shoulders bowed under a weight he had not carried before. He was grieving, for he had great wealth.

Jesus watched him go, then turned to his disciples, his expression bleak. “How hard it is for the rich to enter the kingdom of God!” The disciples were perplexed; wealth was a sign of God’s blessing. But Jesus pressed the point, his words stark. “Children, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God.”

They were astonished, utterly confounded. “Then who can be saved?” they asked, their voices a chorus of despair.

Jesus looked from face to anxious face. “With man this is impossible,” he said, holding their gaze. “But not with God; all things are possible with God.”

Peter, ever the spokesman for their sacrifices, blurted out, “We have left everything to follow you!”

The tenderness returned to Jesus’s voice, a warmth that held a note of unutterable sorrow. “Truly I tell you,” he said, “no one who has left home or brothers or sisters or mother or father or children or fields for me and the gospel will fail to receive a hundred times as much in this present age: homes, brothers, sisters, mothers, children and fields—along with persecutions—and in the age to come, eternal life. But many who are first will be last, and the last first.”

They walked on, the lesson sitting heavily upon them. The road began to climb. Jerusalem was now a palpable presence ahead, a destiny. Jesus was walking ahead again, and the disciples followed, amazed, but a cold fear was beginning to creep into their hearts. Those with him were afraid.

He took the Twelve aside once more, on a barren stretch of the road. His words were plain, stripped of parable. “We are going up to Jerusalem,” he said, “and the Son of Man will be delivered over to the chief priests and the teachers of the law. They will condemn him to death and will hand him over to the Gentiles, who will mock him and spit on him, flog him and kill him. Three days later he will rise.”

The words were too concrete, too vile. They could picture the spittle, hear the crack of the whip. They refused to picture the rest. It was James and John, the sons of Zebedee, who broke the terrible silence. They came forward, a shared ambition burning in their eyes. “Teacher,” they said, “we want you to do for us whatever we ask.”

“What do you want me to do for you?” he asked.

“Let one of us sit at your right and the other at your left in your glory.”

The other ten heard it, and a wave of indignant muttering passed through them. Not at the prophecy of suffering, but at this brazen grab for position.

Jesus sighed. “You don’t know what you are asking. Can you drink the cup I drink or be baptized with the baptism I am baptized with?”

“We can,” they said quickly, confidently. They were thinking of a cup of honor, a baptism of triumph.

“You will drink the cup I drink and be baptized with the baptism I am baptized with,” Jesus said, and there was no condemnation in it, only a stark confirmation of a future they could not yet fathom. “But to sit at my right or left is not for me to grant. These places belong to those for whom they have been prepared.”

He called them all together. The afternoon sun cast long shadows. “You know that those who are regarded as rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their high officials exercise authority over them. Not so with you.” He paused, letting the contrast sink in. “Instead, whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wants to be first must be slave of all. For even the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.”

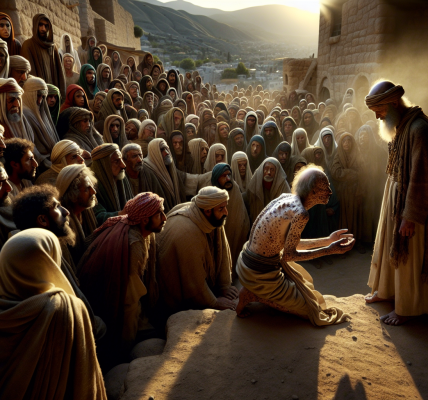

The words echoed as they approached Jericho, the last major stop before the final ascent to the holy city. The noise of the crowd was different here—a constant, bustling din of commerce and travel. As they were leaving Jericho, with a great crowd still following, a commotion arose at the outskirts. A blind man, Bartimaeus, was sitting by the roadside begging. He heard the noise of the crowd thickening and asked what was happening.

“Jesus of Nazareth is passing by,” they told him.

He began to shout, “Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me!” The title, “Son of David,” was a spark in the dry tinder of the crowd. Many rebuked him, telling him to be quiet. But he shouted all the more, “Son of David, have mercy on me!”

Jesus stopped. The procession behind him jostled to a halt. “Call him here,” he said.

The people’s attitude changed instantly. Now they turned to the blind man, their voices encouraging. “Cheer up! On your feet! He’s calling you.” Throwing his cloak aside—his one possession of any value, his means of gathering alms—Bartimaeus jumped to his feet and came to Jesus.

“What do you want me to do for you?” Jesus asked him. The same question he had asked the ambitious brothers.

The blind man did not ask for a place of honor. His request was stark, fundamental, born of a lifetime of darkness. “Rabbi, I want to see.”

“Go,” said Jesus, “your faith has healed you.” And in that moment, the world—a blur of light and shadow, a concept known only by sound and smell and touch—crashed into Bartimaeus with a brilliance that made him gasp. Colors, faces, the dust hanging in slanting golden light, the worn features of the man from Nazareth who was still watching him with a look of deep compassion.

Bartimaeus did not go, as instructed. Instead, he joined the crowd and followed Jesus along the road, his own voice now part of the chorus, praising God. And all the people, when they saw it, gave praise to God as well. They continued upward, the blind man who now saw walking beside disciples who were only beginning to understand how terribly blind they had been. The road to Jerusalem stretched before them, paved with paradox: to gain, you must lose; to be great, you must serve; to live, you must die; and the one who saw nothing had been the first to truly see who was passing by on the road.