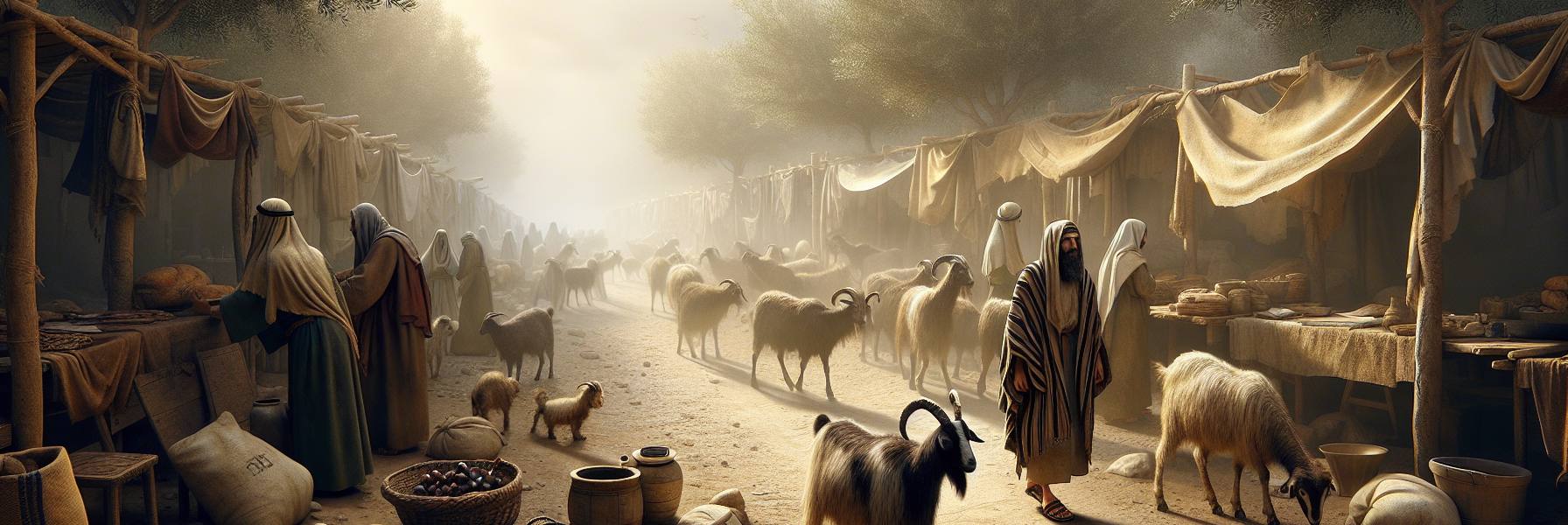

The dust of the road was a fine, persistent powder that coated everything—the leaves of the olive trees, the wool of the stray goats, even the taste of the bread Ezra bought at the market. It was the kind of dust that worked its way into the seams of your tunic, into the cracks of your sandals, a constant, gritty companion. Ezra, a scribe with careful hands and a mind that turned in careful circles, felt it now as he walked the path from Sepphoris back to his smaller village. His errands were done, the ink and parchment secured in his bag, but the real weight he carried was in his thoughts.

The morning’s synagogue service had chafed at him. Jairus, a merchant of some success, had made a great show of his donation for the poor, his voice carrying to the very back where Ezra sat. Later, old Micah had prayed near the front, his arms outstretched, his words a rolling, public performance of piety that drew many eyes. There was nothing technically wrong with any of it, Ezra reasoned. Yet it left a sourness in his spirit, like bad wine. It felt like a transaction, a settling of accounts with an audience, not with God.

Seeking a quieter way home, he turned onto a path that skirted the edge of a farmer’s field. The late afternoon sun was long and golden, catching the heads of wheat in waves of light. It was here he saw a figure sitting on a low stone wall, surrounded by a small crowd. It was the rabbi from Nazareth, the one they called Yeshua. Ezra had heard fragments of his teaching—whispers of a different kingdom. He slowed his step, lingering at the edge of the group, not wanting to be seen, yet drawn in.

Yeshua wasn’t declaiming like the orators in the city. He spoke as if continuing a conversation, his eyes moving across the faces of farmers and fishermen, a tired mother with a child on her hip. He spoke of giving.

“When you do your acts of charity,” Yeshua said, his voice clear and carrying on the still air, “don’t be like the actors, blowing a trumpet in the streets. They’ve already received their payment in full, in the applause of others.” He nodded back toward the distant town. “When you give, your left hand shouldn’t know what your right hand is doing. Do it in secret. Then your Father, who sees what is done in secret, will attend to you.”

Ezra’s fingers, stained with ink, tightened on the strap of his bag. His left hand, his right hand. The image was so foolish, so impractical, and yet it pierced him. He thought of his own meticulous records, the slight feeling of virtue when he dropped his coins in the synagogue box. It was never with a trumpet, but was there not, in his heart, a tiny, silent ledger?

The talk turned to prayer. Yeshua’s tone grew almost weary. “And when you pray, don’t be like the actors there either. They love to stand and pray in the synagogues and on the street corners, to be seen by people. They, too, have their reward.”

Ezra saw Micah’s fervent pose in his mind’s eye. He felt a flush of shame, remembering his own carefully constructed prayers, the ones he mentally rehearsed for clarity and depth, should anyone overhear.

“But you,” Yeshua continued, and his gaze seemed to soften, to include even Ezra lurking in the back, “when you pray, go into your inner room, close the door, and pray to your Father who is in secret. And your Father, who sees in secret, will respond.”

An ‘inner room.’ Ezra’s house was small. The only truly private space was the cramped storage room where he kept his parchments. It smelled of dust and sheepskin. The idea of praying there, amidst the clutter, without a single beautiful phrase prepared, felt strangely vulnerable, and immensely inviting.

Then the rabbi began to give them words. Not a performance piece, but a framework, simple and profound as a loaf of bread. “Our Father in heaven, let your name be held in reverence. Let your kingdom come, let your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven…” Ezra found his own lips moving silently. The petitions were basic: daily bread, forgiveness, deliverance from the evil that coiled in the world and in one’s own heart. It was a prayer for dependents, for children, not for spiritual champions. It acknowledged need. Ezra, the learned scribe, felt his complicated anxieties about status and correctness begin to unravel, replaced by a simpler, sharper hunger.

He spoke of fasting, too—not with a gloomy face to show the world the struggle, but with a washed face, anointed hair, so that the sacrifice was purely between a person and God. Every act, Yeshua was saying, was being seen. But the audience that mattered was not the one in the market square.

The sun dipped lower, painting the field in deeper gold. Yeshua’s voice took on a different texture, warmer, almost maternal. “Stop storing up treasures for yourselves on earth, where moth and rust consume, and where thieves break in and steal. But store up treasures for yourselves in heaven… For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.”

Ezra looked down at his bag of parchment and ink, his most precious possessions. He thought of Jairus and his silks. All of it was subject to moths, to decay, to loss. His heart, he realized, was a nervous watchman, constantly patrolling those fragile storehouses.

The final words settled over the gathering like a soft blanket. “Consider the birds of the sky,” Yeshua said, pointing to a flock of sparrows tumbling over the wheat. “They don’t sow or reap or gather into barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Aren’t you worth much more than they?” He gestured to the lilies growing wild by the wall, their simple robes a purple more glorious than Solomon’s famed splendor. “If God clothes the grass of the field, which is here today and tomorrow is thrown into the oven, won’t he do much more for you, you of little faith?”

The phrase stung—‘you of little faith’—and Ezra knew it was for him. His faith was a thing of scrolls and statutes, a fortified city constantly under threat from worries about food, drink, clothing. Tomorrow’ anxieties were his constant, unwelcome companions.

“So don’t worry, saying, ‘What will we eat?’ or ‘What will we drink?’ or ‘What will we wear?’… Your heavenly Father knows you need all these things. But seek first his kingdom and his righteousness, and all these things will be given to you as well. So don’t worry about tomorrow. Tomorrow will worry about itself. Today’s trouble is enough for today.”

The crowd began to disperse, murmuring. Ezra stood rooted. The dust was still there, the road home still long. Nothing in his outward circumstances had changed. But the axis of his world had shifted. It was as if he had been straining to read a document in a dim, crowded room, and someone had quietly opened a shutter, letting in a clear, single shaft of light.

He did not go straight home. He walked to the edge of a small quarry, abandoned and quiet. He sat on a rock, and for the first time in memory, he prayed without a single thought to how it sounded. He spoke of the dust, of the sour feeling, of his anxious ledger-keeping heart. He asked, simply, for bread, for forgiveness, for deliverance. He said, “Your kingdom come,” and tried to mean it.

When he stood, the worries for tomorrow were still there, but they seemed smaller, quieter, like chattering merchants outside a door he had decided, for this moment, not to open. He walked home in the twilight, the words weaving through his mind: *The Father who sees in secret. Where your treasure is. Consider the lilies.* The air was cool now, and the first stars were beginning to prick through the deep blue of the sky, countless, silent, and held in an order he did not need to understand. It was enough, for today.