The air in my small room was still, thick with the smell of dried ink and papyrus, but in my mind, I heard the distant crash of waves. The sea was far from here, a memory from boyhood, yet the scroll before me brought its roar close. It was the word of the Lord, given to Nahum, against Nineveh. I was not a prophet, only a scribe with a trembling hand, but the vision demanded to be written, to be felt, not just read.

It began not with a shout, but with a terrible, familiar sound—the groan of a wooden cart axle, dry and unlubricated, bearing an impossible weight. That was the city. Nineveh, the bloody city. The words on the page dissolved, and I saw it.

She was not just a place of walls, but a woman, a queen, draped not in linen but in the rust-colored crust of dried blood. It was on her skirts, in the folds of her garments, a patina of conquest. Every brick in her towering walls was mortared with lies; every gateway, a gullet that swallowed nations whole. The noise was a constant, deafening din: the shriek of the slave-driver’s whip, the hollow clatter of endless chariots on cobbles, the distant, weeping echo from a hundred plundered villages. Her scent was not of market spices, but of solder from the armourer’s forge, of fear-sweat, and underneath it all, the sweet, cloying stench of decay her perfumes could never quite conceal.

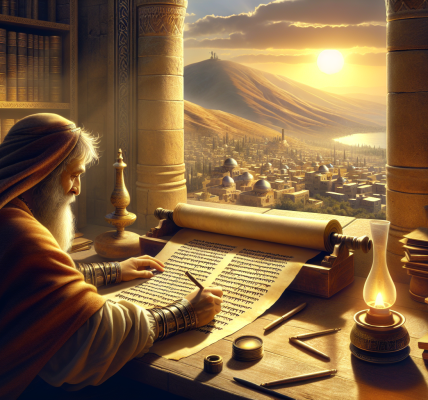

And then, the vision shifted. I heard it before I saw it: a hissing, like a torrent of rain on a hot road. It was the sound of whips cracking, of charging horses, of rattling wheels. The Lord of Hosts was driving His own chariot. His flashing sword was not mere steel; it was the lightning that split the sky over the plains. His glittering spear was the fever-light in the eyes of the besieging armies. The hills, the very earth, trembled as He came.

There would be a battle, yes. But the vision showed me the aftermath. The great queen, the mistress of sorceries, would be exposed. She would be lifted by the hem of her blood-soaked robe and cast onto the filth of the street. Her divine secrets, the whispered incantations that bound nations to her, would mean nothing. The idols she trusted would be smashed, their wooden heads rolling into the gutters like common rubbish. And the nations she enslaved would pass by, shaking their heads, hissing through their teeth at the ruin of her. All her strongholds, the prophet said, would be like fig trees heavy with first-ripe fruit. A shake of the branch, and the corpses of her defenders would fall into the mouth of the conqueror.

I paused, my fingers cramped. The image was too precise, too humiliating. I saw the gates of her rivers flung wide—not by defenders, but by some inner treachery, a panic in the night. The palace, that labyrinth of polished alabaster, would dissolve. It would *melt*. Not burn, but turn to slurry like wax in a fire, the great statues of bulls with human faces sliding into formless puddles on the floor. Her troops were women, the vision declared. Not a slight against women, but a crushing metaphor: in the moment of truth, their strength would turn to a paralyzing terror. The bars of her gates, cedar from Lebanon, oiled and immense, would be consumed as if by a locust swarm in a summer field—eaten from within until they were mere dust.

This was the heart of it. This was her sin, woven into her very foundations. She was a city of endless commerce, but it was the commerce of lives. She was a hive of merchants, trading in souls, her elite as numerous as the stars, her satraps like swarming locusts. But when the sun of judgment rose, they would vanish, taking to the hills, leaving no trace, no one to gather them. The shepherds would sleep, the nobles slumber in the dust. The people would be scattered on the mountains with none to gather them.

I leaned back, the weariness deep in my bones. The final picture was one of devastating, quiet irony. All who heard of her fall, the vision said, would clap their hands. For who had not felt the endless cruelty of her shadow? Her wound was mortal, a sickness unto death. And the report of it would bring a kind of grim, relieved joy to every coastland.

Then, the last line, almost an afterthought, a sigh from the prophet: *There is no easing of your hurt; your wound is grievous.*

I set the stylus down. The story was not mine, but the telling of it had left me spent. Outside my window, a ordinary sparrow pecked at the dirt. The roar of the distant, fallen sea was gone. All that remained was the silence after the judgment, and the stark, terrible truth that the machinery of empires, for all its noise and blood and grandeur, rests upon foundations of sand. And the tide, when it is sent, is inexorable.