The rain had finally come.

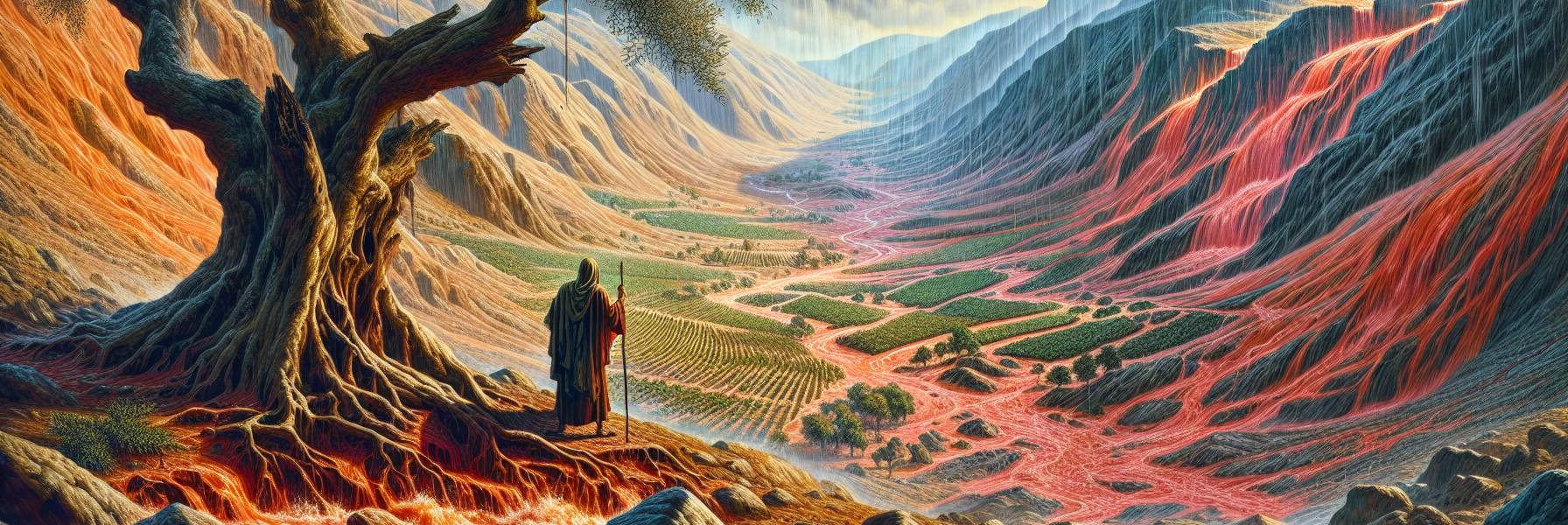

It wasn’t the gentle, life-giving rain of my youth, the kind that soaked into the terraces with a sigh. This was a violent, drenching torrent, sluicing down the rocky slopes of the mountains around Jerusalem, carving fresh gullies in the long-neglected hills. I stood under the meager shelter of a leaning olive tree, its trunk gnarled and hollow, and watched the water run red. Red with the iron-rich soil of the highlands, soil that hadn’t felt such a downpour in years.

They called these the mountains of Israel. To me, they were just bones. Bleached, barren bones. I remembered my grandfather’s stories, tales of these slopes clothed in vineyards, the air thick with the scent of thyme and the sound of bees. Now, the only scent was dust, and the only sounds were the scrabble of lizards and the lonely wind through rocks. The nations around us, the Edomites who had crept into the abandoned villages, they looked at these hills and scoffed. “Aha!” they said, their voices carried on merchant caravans. “The everlasting heights are now our possession. They are desolate, so they have been given to us for food.” The land itself had become a taunt.

I was an old man, a keeper of records with ink-stained fingers and a memory too long for my own good. I had seen the slow death. It began not with the siege engines of Babylon, but earlier, in the heart. We had treated this land, this promise, like a common harlot. We poured out our idols on every high place, our altars to no-gods staining the very stones. The blood of the innocent cried out from the ground, mingling with the blood of our false sacrifices. The land, it seemed, had taken a deep, sickened breath and then held it. The rains stopped. The soil tightened its fist. What the sword didn’t take, the famine did. And we were scattered, a bitter harvest sown to the four winds.

But that night, as the storm growled and the old olive tree shuddered, a different memory stirred. Not a story from my grandfather, but a word from the prophet, from Ezekiel, spoken years ago in the choking dust of exile. We had dismissed it as the ravings of a broken man, a beautiful lie to soothe a terminal wound. He had spoken to these very mountains. To the bones.

The words came back to me now, not as a recited scripture, but with the force of the rain itself, each drop a syllable. *“But you, O mountains of Israel, shall shoot forth your branches and yield your fruit to my people Israel, for they will soon come home.”* I looked at the skeletal branches above me. It was impossible.

The rain began to ease. A strange, greenish light broke under the cloud-cover. I stepped out from the shelter, my sandals sinking into the sudden mud. And then I saw it. Not a vision, but a fact. Where the red water had pooled in a hollow, it wasn’t just washing away. It was *soaking in*. For the first time in decades, the ground was not repelling the gift from heaven, but drinking it. Deeply.

The weeks that followed were a quiet miracle. It wasn’t dramatic. No vines sprouted overnight. But the grey-green of the thorn bushes softened. A stubborn, wiry grass began to appear in patches, not just the yellowed tufts of before. I took to walking the same shepherd’s path each dawn. One morning, I found a tiny, determined shoot of wild barley pushing up between two stones. I knelt, my old knees cracking, and touched it. It was cool and firm with life.

And the people began to return. Not in triumphant caravans, but in ragged, hesitant clusters. Families from the north, from the coasts of Greece and the cities of Egypt, drawn by a rumor, a whisper they couldn’t explain. They came back to their allotted lands, not to grand estates, but to overgrown fields and collapsed homes. They saw the same bones I had seen. But they began, with a weary hope, to clear the stones.

The real change, though, was harder to name. We were the same people, with the same tendency to quarrel, the same old fears. Yet, something was… absent. The frantic anxiety that had driven us to every foreign altar, the grasping desperation that had made us cheat our neighbors—it had receded, like a fever breaking. We worked the stubborn ground, and we argued over boundary lines, but the idol-makers found no market. The old, easy curses died on our lips. It was as if the land’s cleansing was also our own. The filth of our ways, the stain of our idolatry, was being washed not just from the hills, but from some inner chamber of the spirit.

Ezekiel’s words, now whispered around cooking fires and at the communal well, took on flesh. *“I will sprinkle clean water on you, and you shall be clean from all your uncleannesses… I will give you a new heart, and a new spirit I will put within you. I will remove the heart of stone from your flesh and give you a heart of flesh.”* A heart of flesh. That was it. We felt the drought, and now we felt the rain. We felt the shame, and now we felt a fragile, tentative yearning—not for gain, but for rightness. It was a vulnerable thing, this new heart. It could be wounded. But it could also love.

I sat on my hill one evening, watching the settlers below. Smoke rose from new hearths. The sound of a child’s laugh, not a cry, carried on the breeze. The mountains were not yet clothed in glory. But they were no longer bones. They were flesh, waiting for the spirit. The promise was not a restored kingdom of gold and power. It was simpler, and more profound. God was doing this, not for our sake—we, the broken vessels—but for the sake of his own holy name, which we had dragged through the mire of the nations. He was causing these ruined towns to be inhabited. He was making the desolate land tilled. And in the quiet, willing work of our hands, and in the strange, soft pull of our renewed hearts, we were, at last, becoming his people. And this scarred, drinking, green-touched earth was, once more, becoming his land.