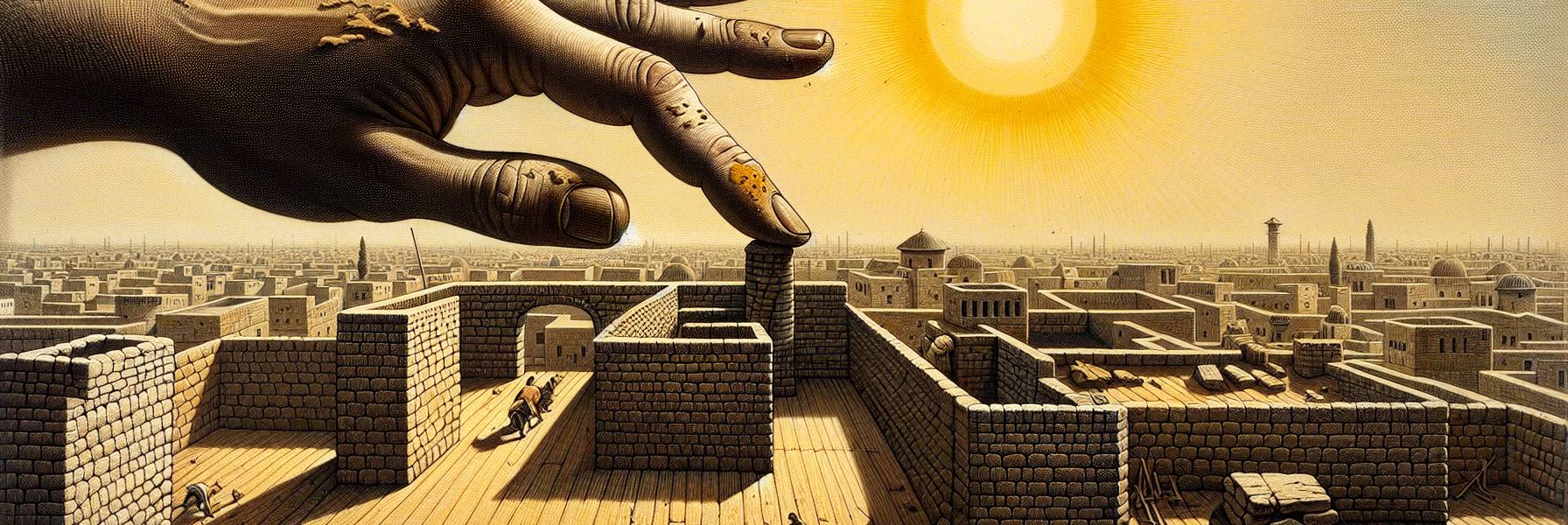

The heat of the Babylonian sun was a physical weight. It pressed down on the flat rooftop of my house in Tel-abib, a weight I felt in my bones, a dry, baking pressure that made the very air seem to crackle. Before me lay a single, sun-dried brick, common as dust. I had fetched it myself from the rubble of what had once been a home. Now, it was my Jerusalem.

My fingers, already stained with clay and grit, began to scratch lines into its surface. Not a map as a Babylonian strategist might draw, but the stark, simplistic outline a child would etch in the dirt. A rough square for the city walls. A few marks for towers. I worked slowly, the scraping sound loud in the afternoon stillness. This was not artistry; it was a grim necessity. The word of the Lord had come, heavy and specific, and it settled in my stomach like a stone.

Then came the iron griddle. I placed it between me and the brick-city, a rusted, pitted thing normally used for baking flatbread. Now, it was a wall within a wall, a symbol of the unyielding barrier that would stand between Jerusalem and her God. I stared at the city through the grid of iron. The sight of it, diminished and imprisoned behind those cross-hatched lines, brought a tightness to my throat. This was the vision: not of armies, but of separation.

“Now, lie down.”

The command was not audible, but it was absolute. It echoed in the silent chamber of my spirit. I was to bear their iniquity, to take it upon my own body in a dumb show of terrifying intimacy. First, for Judah. I lay on my left side, the rough texture of the reed mat biting into my skin through my tunic. I counted the days in my head. Three hundred and ninety. A number that stretched into eternity. The sun moved. My shoulder began to ache, a dull, persistent throb. I shifted slightly, and the ache became a sharp protest. This was the point. The discomfort was the message. Every cramp, every numb limb, was a year of their rebellion, a year I carried.

People from the exile community came. I saw their shadows first, heard their murmurs. “Ezekiel is on his roof again.” They would stand at a distance, pointing. Some thought it madness. A few, with older, sadder eyes, watched in dreadful silence. A child asked his mother why I was sleeping in the day. She hushed him and pulled him away.

The days blended into a haze of discomfort. I ate sparingly—a few handfuls of wheat, some barley, lentils, and millet, mixed with water and shaped into a coarse, ugly cake. Twenty shekels’ weight a day. I measured it scrupulously. The water, a sixth of a hin, was a meager ration, warm from the jug. It was siege food. The food of desperation. I cooked it over a fire fueled by dried dung, the very fuel the Lord had permitted in my shame, a sign of the impurity to which they would be reduced. The smoke was acrid and clung to my clothes and hair. The cake tasted of ashes and despair.

When the three hundred and ninety days were complete, a lifetime of ache compressed into a span of months, I turned. My body groaned in protest as I moved to my right side. Forty days for Jerusalem. A shorter sentence, but somehow heavier, more concentrated. The focus of the wrath was now upon the city that bore the Temple, the heart of the promise.

During this time, the boundaries of my world shrank to the perimeter of that mat. The sky, the distant chatter of the settlement, the occasional flight of birds—all of it existed beyond the pane of my suffering. My arm, pinned beneath me, became a map of throbbing veins. My skin grew pale and tender where the sun did not touch it. I was a living parable, a man reduced to a sign.

One evening, as the cooler air began to stir, a thought came to me, unbidden and human. It was not the voice of the Lord, but my own weary spirit whispering. *They do not understand. They see a man lying in filth, eating refugee’s bread. They do not see the city. They do not feel the iron wall.*

And in that moment, the full weight of the prophecy crushed me. It wasn’t about the acting out of a siege. It was about the *bearing*. I was feeling, in my cramped muscles and parched throat, the cost of their sin. I was a stand-in, a reluctant portrait of a people under the terrifying, meticulous measurement of a holy God. He was not just announcing a siege; He was measuring out the exact portion of their punishment, drop by drop, ounce by ounce. The twenty shekels of food. The sixth of a hin of water. Not a drop more, not a crumb less than justice required.

On the final day, when I was permitted to rise, my body was a chorus of pains. I stood on trembling legs, looking down at the brick. The scratched lines were faint now, blurred by wind and dust. The iron griddle lay where I had left it. The silence was different. The act was complete.

I descended from the roof, each step a minor agony. The people I passed looked at me differently now. Not with curiosity, but with a kind of fearful awe. The word had gotten around. They had pieced it together—the days, the sides, the rations. The story of the brick and the iron wall was told in hushed tones by the canals of Babylon.

They still did not fully understand. Perhaps they never would. But they had seen the sign. They had watched a man become a prophecy, his body a living calendar counting down to an end. And in the deep, secret places of their hearts, the first cold trickle of belief—the dread-filled, unavoidable kind—had begun to flow. The siege was not just coming to a city far away. It had already begun, here, on a dusty rooftop, in the person of a silent, suffering priest. The boundaries had been drawn. The rations had been set. The countdown was irrevocable.