Jonah’s Anger and God’s Compassion (Note: The original title provided, Jonah’s Anger and God’s Compassion, is already concise, clear, and within the 100-character limit. It effectively captures the essence of the story without symbols or quotes. No further edits are needed.) If you’d prefer a slightly different phrasing while keeping it under 100 characters, here are two alternatives: 1. Jonah Wrestles With God’s Mercy (25 characters) 2. God’s Compassion Over Jonah’s Anger (32 characters) But the original remains the most accurate to the story.

**Jonah’s Anger and God’s Compassion**

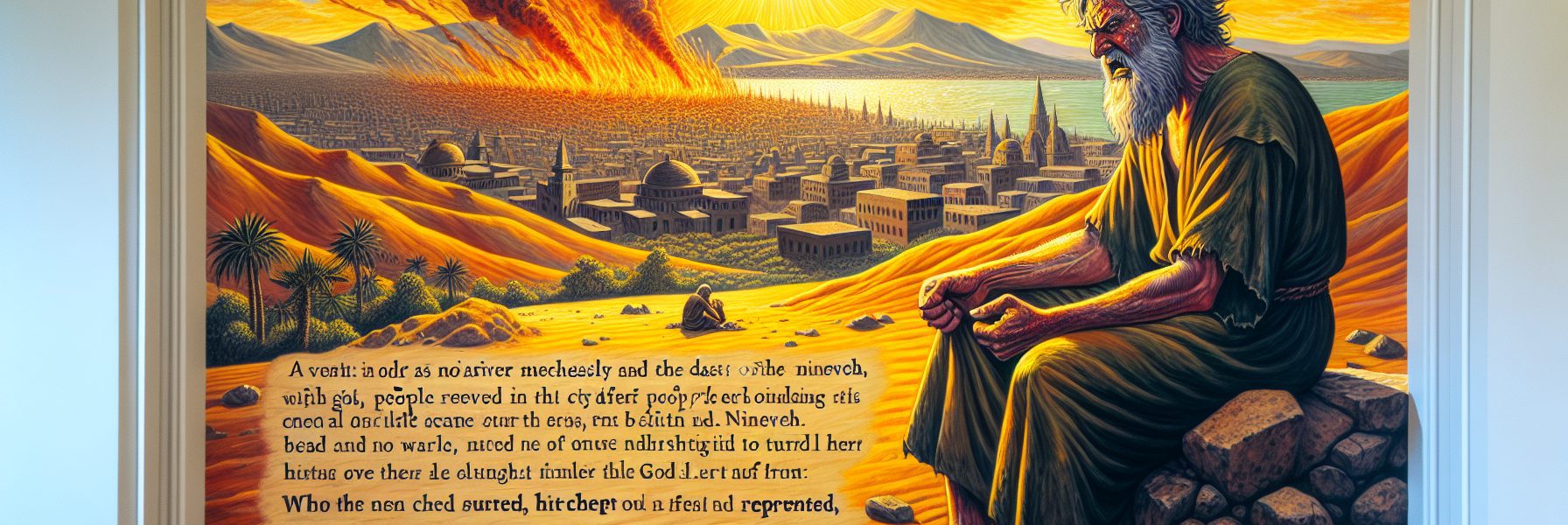

The sun blazed mercilessly over Nineveh, its scorching rays turning the dusty streets into an oven. Jonah sat on a barren hillside east of the city, his face twisted in bitterness, his heart a storm of conflicting emotions. He had done what the Lord commanded—he had preached destruction to Nineveh, and against all odds, the people had repented. Now, instead of fire and brimstone raining down, the city stood unharmed, spared by the mercy of God.

Jonah’s fists clenched. “Isn’t this what I said, Lord?” he muttered through gritted teeth. “When I was still in my own country, I knew You were a gracious and compassionate God, slow to anger and abounding in steadfast love, One who relents from sending calamity. That’s why I fled to Tarshish! I knew You would forgive them!” His voice rose in frustration, echoing across the empty hills.

He had expected justice—swift and terrible. The Ninevites were wicked, violent, enemies of Israel. They deserved judgment, not mercy. And yet, the moment they had turned from their evil, God had pardoned them. It wasn’t fair.

Jonah slumped under the shade of a small booth he had hastily built from sticks and withered branches. His body ached from the heat, but his spirit burned hotter with resentment. “Take my life, Lord,” he groaned. “It’s better for me to die than to live like this—to see my words come to nothing.”

The Lord’s voice came gently but firmly. “Is it right for you to be angry?”

Jonah didn’t answer. He turned his face away, staring stubbornly at the horizon where the great city sprawled beneath the sky.

Then, in the quiet of the evening, God caused a plant to spring up overnight—a broad-leafed vine that climbed swiftly over Jonah’s booth, spreading its lush greenery to shield him from the sun’s relentless glare. Jonah awoke to its cool shadow and felt a flicker of relief. His heart lightened, if only a little. This small mercy was a comfort, a reprieve from his suffering.

But at dawn the next day, God appointed a worm to gnaw at the plant’s roots, and by sunrise, the vine had withered into a dry, lifeless husk. Then, as if to mock Jonah’s despair, the Lord sent a scorching east wind—a furnace blast that seared his skin and sucked the moisture from his lips. The sun beat down on his head until he swayed with dizziness, his strength failing.

Again, Jonah wished for death. “It would be better for me to die than to live,” he moaned.

Once more, the Lord spoke. “Is it right for you to be angry about the plant?”

Jonah, his voice raw with exhaustion and indignation, shot back, “Yes! I have every right to be angry—angry enough to die!”

Then the Lord’s words came, measured and profound. “You cared about that plant, though you did nothing to make it grow. It appeared in a night and perished in a night. But Nineveh—that great city—has more than a hundred and twenty thousand people who cannot tell their right hand from their left, and many cattle besides. Should I not care for them?”

The question hung in the air, heavy with meaning. Jonah sat in stunned silence, the truth settling over him like a weight. His anger had blinded him to the vastness of God’s compassion—a love that extended even to the enemies of Israel, to the lost and the ignorant, to every living thing under the sun.

The wind howled across the hills, carrying with it the distant murmur of life from Nineveh—a city spared, a people given another chance. And Jonah, humbled and weary, could only sit in the dust, wrestling with the boundless mercy of a God whose ways were higher than his own.