The air in the courtyard still tasted of dust and dread, though the sun was now high. Mordecai stood before the king’s inner gate, the same rough sackcloth exchanged for robes of blue and white, a great golden crown upon his head, and the royal signet ring, heavy and cold, upon his finger. It was a weight he was still learning to bear. The decree of destruction, sealed with this very ring just months before, haunted the very threads of the fabric. It hung in the silence between the shouts of the palace guards.

Inside, the queen’s chambers were no longer a place of perfumed secrecy but a hub of desperate industry. Esther had not rested. The victory over Haman was a hollow echo in a house still scheduled for demolition. She fell before the king again, not with the graceful terror of her unsummoned entry, but with the ragged urgency of a drowning woman who has found a rope but cannot yet climb to safety. The tears she shed now were not for herself. They were hot, angry tears for every Jewish family in every province from India to Cush, for the children who would wake to a day marked for slaughter.

“How can I bear to see disaster fall on my people? How can I endure the destruction of my kindred?” Her voice, usually so measured, cracked like dry clay.

Ahasuerus, a man more accustomed to managing feasts than fates, extended the gold scepter. He seemed older suddenly, the lines around his eyes deepened by the grim arithmetic of his own earlier edict. “See,” he said, the word weary, “I have given Haman’s estate to Esther, and he has been impaled on the stake for plotting against the Jews. You may write in the king’s name as you please concerning the Jews, and seal it with the royal ring. For an edict written in the king’s name and sealed with the royal ring cannot be revoked.”

It was not a clean solution. It was a bureaucratic knot, a second decree to tangle with the first. But it was the only thread they had. The royal secretaries were summoned, their faces pale and attentive. It was the third month, the month of Sivan, on the twenty-third day. The same pens that had scratched out the sentence of death now hovered over fresh scrolls.

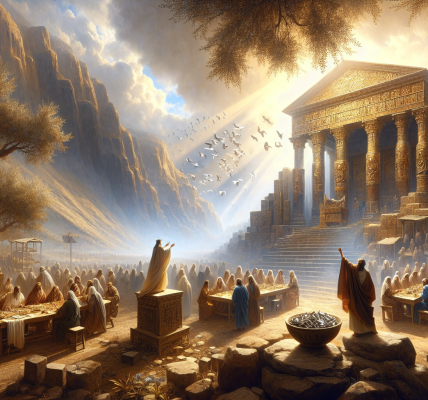

Mordecai dictated, his voice low and steady, but his hands trembled slightly. The words were not just ink; they were a shield, a sword, a permission to breathe. He wrote to every satrap, governor, and official of the hundred and twenty-seven provinces, in every script and every language: to the Jews, and to the officials, and to the governors. He gave the Jews in every city the right to assemble and protect themselves; to destroy, kill, and annihilate any armed force of any nationality or province that might attack them, their women, and their children, and to plunder the property of their enemies. The day set for this was the same day—the thirteenth day of the twelfth month, Adar.

A copy of the text was to be issued as law in every province, published to all peoples, so the Jews would be ready for that day to avenge themselves. Couriers, mounted on the king’s own swift horses bred from the royal stud, sped out, urgent and pressed, by the king’s order. The law was issued in the citadel of Susa as well.

Mordecai left the king’s presence then, his new robes a brilliant tapestry against the sun-bleached stones of the city. But the grandeur was a shell. The man inside was hollowed out by fear and fasting, now flooding with a relief so profound it felt like a new kind of pain. He did not look like a viceroy; for a moment, he looked like an old man blinking in the sudden light.

The reaction in Susa was not immediate silence, then cheers. It was a deep, seismic shift. A sound rose from the Jewish quarter, a sound that began as a murmur of disbelief, then a weeping, then a shout that fractured into a thousand shouts of pure, undiluted joy. It was the sound of a death sentence being ripped in two. Light and gladness, feast and holiday—words from the scrolls became the substance of the streets. People embraced, strangers, their faces wet. Many from the other peoples of the land declared themselves Jews, because the dread of the Jews and of Mordecai had fallen on them. It was not just fear; it was the stark, unsettling witness to a reversal so complete it hinted at a hand moving behind the thrones.

In the provinces, when the king’s command and his edict arrived, and when the Jews in every city had gathered to hear the words that granted them the right to stand, the joy was a mirror of Susa’s, multiplied across mountains and deserts. There was gladness and joy among the Jews, a feast and a holiday. The air itself seemed to change. Where there had been the metallic taste of fear, now there was the smell of bread baking for celebration, the scent of oil for lamps that would not be extinguished. They were still facing the thirteenth of Adar. The old decree, that irrevocable law, still stood. But they would not face it cowering in hidden rooms. They would stand together, and they would live. The story of that month, from the bitterness of Nisan to the tentative hope of Sivan, was not about the avoidance of conflict, but the granting of a face to face it. And in that grant, in that fragile, written authority, was a kind of salvation.