The air in Jerusalem that morning held the peculiar weight of washed stone and old dust. It was cool, the kind of chill that clings to shadowed places just before the sun asserts itself. The people had been gathering since first light, a quiet, deliberate tide flowing into the broad square before the Water Gate. They wore sackcloth, not as a uniform, but in a ragged assortment of rough tunics and ashes smudged on foreheads—improvised, personal, earnest.

They separated themselves, a tangible act. Not from each other, but from something unseen—from the slow drift of compromise, from the forgotten language of covenant. They stood, a nation of prodigals on their own soil, and the silence was not empty but thick, a shared inhalation before a confession.

Then Ezra, and with him other Levites, ascended the high wooden platform built for such readings. He did not look like a triumphant reformer that day. He looked old, his shoulders a slope of carried burdens. He unrolled the scroll, the leather crackling in the hush. He began to read from the Book of the Law, not for instruction this time, but for indictment. The words fell like clear water on parched ground, and for hours they listened. The sun climbed, painting the eastern wall in gold, but the crowd did not stir. The words cut, and the cutting was a mercy.

When the reading ended, a different movement began. The Levites scattered among the people, not to lead a cheer, but to quiet them further. “This day is holy,” they murmured, hands pressing gently on trembling shoulders. “Do not mourn. Do not weep.” But the weeping had already begun, a soft, shuddering sound that rippled through the square. It was the sound of memory returning, painful and essential.

The next day, the heads of families gathered again. This time, it was not for listening alone, but for speaking. A man named Jeshua, along with Bani and others, stood before them. Their voices, when they came, were not oratorical. They were ragged, straining under the gravity of what they had to say. “Stand up,” one of them said, simply. “Bless the Lord your God.”

And so they stood, a forest of weary humanity, and then as one body, they bowed their heads and fell to their knees, foreheads pressing against the cool, dusty stone. What followed was not a prayer of request, but a long, unsparing remembering. It was history recited as liturgy, a family telling its darkest, most truthful story.

“You are the Lord,” the voice rose, thin against the sky, “you alone. You made the heavens, the heaven of heavens, with all their host, the earth and all that is on it, the seas and all that is in them. You gave them life, and the heavenly host worships you.” It began not with them, but with everything—a firm anchoring in the sheer, overwhelming *otherness* of God. This was important. The story of their failure needed the vast canvas of His faithfulness.

They spoke of Abraham, found in the mud-brick chaos of Ur, his heart faithful because God had made it so. They recounted the covenant, not as a dry contract, but as a promise whispered into the emptiness of a barren old age, and then made bone and blood in Isaac and Jacob.

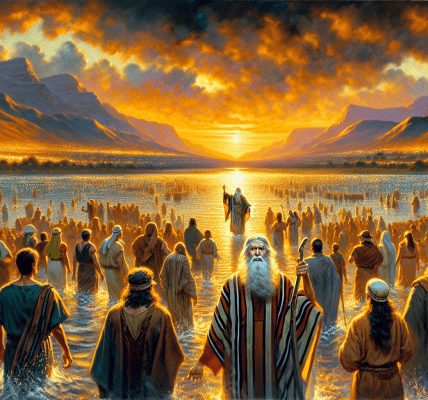

Then, the pivot: Egypt. The telling grew visceral. They did not gloss over the horror. “You saw the affliction of our fathers in Egypt,” the voice choked, “and heard their cry at the Red Sea.” They described the signs and wonders not as distant magic, but as the terrifying, liberating intrusion of the Holy into the machinery of a slave empire. The pillar of cloud and fire was not a symbol; it was a guide that was also a shield, a light that was also a judgment.

They spoke of Sinai, the mountain smoking like a furnace, the law given from a terrible glory. They named the gift: “right rules and true laws, good statutes and commandments.” And then, with a jarring, painful honesty, they named the immediate, breathtaking betrayal: the calf, the molten image, the revelry at the foot of the very mountain that still trembled with the footfall of divinity.

Here, the rhythm of the prayer established itself, a cadence that would beat like a sick heart through the rest of the confession: *You gave. We rebelled. You were gracious. We forgot.*

They traced it through the wilderness—the manna, the water from rock, the clothes that did not wear out. “They lacked nothing,” the Levite said, wonder and shame mixing in his tone. And alongside it: the pride, the stubbornness, the conspiracies to return to the phantom safety of Egypt.

They came to the land. The prayer did not celebrate conquest as mere victory; it framed it as a gift of grace to a faithless people. “You subdued kingdoms before them… the land they possessed, and they ate its fruit and were filled.” Full bellies, fortified cities, vineyards they did not plant. And the response? “They became disobedient and rebelled. They cast your law behind their back.”

The voices of the Levites now took on the weariness of the prophets. They spoke of years, decades, centuries of warning, of a relentless divine patience that sent messenger after messenger, who were met with mockery and murder. The history was a slow-motion tragedy, a people systematically dismantling the very house that sheltered them.

Then, the inevitable crunch of stone and iron. “You gave them into the hand of their enemies, who made them suffer.” The prayer did not shy from God’s agency in their punishment. It was not fate or bad luck; it was the deliberate, painful withdrawal of a protective hand, letting the consequences of their chosen path wash over them. The exile was named: a scattering, a byword, a humiliation.

But the terrible, beautiful hinge of the prayer was this: even in the wreckage, the character of God held firm. “In your great mercies you did not make an end of them or forsake them, for you are a gracious and merciful God.”

Now, the prayer arrived at the present moment, at the dust of this square, at the smell of their own sackcloth. “And now, our God, the great, the mighty, the awesome God, who keeps covenant and steadfast love…” The titles piled up, not as flattery, but as a foundation for a desperate plea. “Let not all the hardship seem little to you that has come upon us.”

They named their current reality: kings from Persia ruling over them, their produce taxed, their bodies in servitude. They were a small remnant in a broken city, the wall around them a fragile thing. And they stood in the full, blinding light of their own complicity. “We are in great distress.”

The confession ended not with a grand solution, but with a act of moral and spiritual placing. “Because of all this, we make a firm covenant and write it.” It was a decision. The long gaze into the mirror of their history, so brutal and so soaked in undeserved mercy, had only one possible end: a voluntary return to the bonds they had spent generations breaking.

The parchment was produced, the ink mixed. The leaders, the priests, the Levites pressed their seals into the soft wax. The document was a promise to obey the Law, a promise regarding marriages, Sabbaths, and temple offerings. It was specific, practical, unromantic. It was the only sane response to the story they had just told.

The sun was high now, the square hot. The people stood, legs stiff, eyes raw. But the weight was different. It was no longer the leaden weight of shame, but the solid, demanding weight of a chosen yoke. They had remembered who God was. They had remembered who they were. And in the space between those two memories, in the painful, gracious gap called grace, they found not an ending, but a place to begin again, on the worn stones of a city they were learning, once more, to call home.