The air in Jerusalem had tasted of dust and despair for months. Not the clean, dry dust of the field, but a gritty, ashen powder that rose from the shattered houses beyond the second wall and clung to the back of the throat. I stood on the rampart, my knuckles white on the sun-warmed stone, watching the Babylonian engineers work. They moved with a terrible, patient certainty. Their siege mounds, those monstrous earthen ramps, had finally bridged the gap between the outer plain and our walls. For eighteen months we had held them. For eighteen months King Zedekiah had clung to the prophet Jeremiah’s words like a man clutching at rotten rope, hearing only the condemnation, never the slim thread of mercy woven within it.

Then, on the ninth day of the fourth month, in the eleventh year of Zedekiah, the city broke.

It wasn’t a glorious last stand. It was a slow, then sudden, unraveling. A section of the northern wall, undermined and battered by rams, groaned like a dying beast and slumped inward. The sound that followed wasn’t a unified war cry, but a deep, metallic roar as the Babylonian guard poured through the breach—a river of polished bronze, dyed horsehair plumes, and focused violence. Our defenders, half-starved and riddled with disease, were swept aside like chaff.

I saw the king’s household stir from a distance, a frantic scattering from the palace like ants from a disturbed nest. Zedekiah, with a handful of his soldiers, did not go to the temple, did not rally the troops. He fled. Under cover of the smoky chaos, as dusk began to bleed into the sky, they slipped out through a gate near the king’s garden, through the brittle reeds of the Kidron valley, heading for the wilderness, for the Arabah. A king, running from his throne.

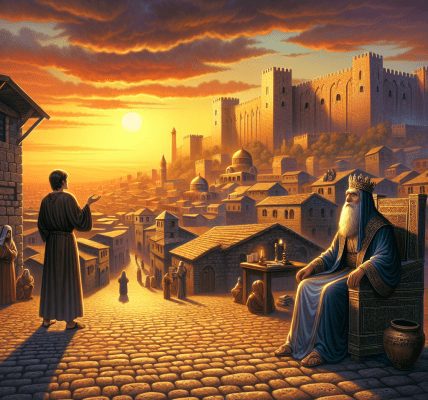

Nebuzaradan, the captain of the Babylonian guard, a man whose very name we had whispered in curses for two years, entered the city the next morning. He took the Middle Gate and sat there, a conqueror holding court at the heart of our wound. His officials, those *rab saris* and *rab mag*, moved through the smoldering streets with clipboards of clay, methodically disassembling our world. The temple, the palace, every substantial house—they put the torch to them. The great walls we had trusted, those mountains of hewn stone, were broken down piece by piece. I watched from a hiding place in the lower city as the fire consumed Solomon’s colonnades, the cedar beams sighing as they fell in great showers of sparks. The smell was not just of smoke, but of melted gold and charred incense.

But the real story, the one whispered in the ruins afterward, was of Zedekiah. The Babylonians hunted him like a prized stag. They ran him to ground in the plains of Jericho, his men scattered to the winds. They brought him, bound in fetters, to the king of Babylon at Riblah, in the land of Hamath. And there, in that foreign place, they pronounced judgment. They slew his sons before his eyes, the last of Judah’s royal line. Then they put out his eyes. The final thing Zedekiah king of Judah ever saw was the death of his future. Blinded, he was dragged in bronze chains to Babylon, to die in a cell, remembering the sight of his fallen children.

As for the people, it was a winnowing. The poor, the vineyard-dressers, the farmers—those who had nothing, they left in the land, gave them vineyards and fields to work. A practical decision by an empire that needed its provinces to produce. But the rest—the officials, the warriors, the craftsmen, the skilled and the dangerous—they took into exile. A long, dusty column shuffling eastward, their freedom exchanged for their lives. I was among them. The strap of a Babylonian soldier’s pack cut into my shoulder as I carried loot from my own city.

Yet, in the midst of this calculated ruin, there was a strange, specific mercy. Nebuzaradan had his orders concerning one man: Jeremiah the prophet. The Babylonian king, Nebuchadnezzar himself, had commanded it: “Look after him. See that no harm comes to him. Do for him whatever he says.” It was staggering. While the city burned, the captain sought out the man whose warnings had gone unheeded. They found him in the court of the guard, where Zedekiah had kept him confined for speaking uncomfortable truths. They pulled him from the chaos, this old, weary man who had prophesied this very disaster, and they treated him with a respect our own king had denied him.

Nebuzaradan spoke to him, not as a captive, but as a dignitary. “Your God pronounced this evil upon this place. Now He has brought it about. It is done. But see, I free you today from the chains on your hands.” He offered a choice: come to Babylon, where he would be cared for, or stay among the shattered remnant in Judah. Jeremiah, whose heart was forever tied to these broken stones, chose to stay. They gave him food and a present, and let him go. I saw him walk away, not toward the exiles’ column, but back into the wreckage of the city, to Gedaliah, the newly appointed Babylonian governor. A free man in a conquered land.

It was a lesson etched in fire and blood. The God who keeps His word of judgment also remembers His word of protection. The city fell because its king would not listen. The prophet lived because a foreign king, an instrument of wrath, chose to heed the divine whisper behind the tumult. And we, the exiles, trudged toward a future we could not imagine, carrying with us the memory of smoke, the ghost of a blinded king, and the bewildering sight of an old prophet walking alone and unshackled through the gates of ruin.