The air in Jerusalem tasted of dust and old stone. It was the thirty-first year of King Josiah’s life, the eighteenth of his reign, and the scroll in his hands felt heavier than any crown. The words, read aloud in the high, clear voice of the scribe Shaphan, still rang in the vaults of his skull. They were not new laws, but forgotten ones; a covenant so neglected its very parchment had crumbled in the Temple storerooms, buried under the pragmatic clutter of maintenance and the quiet accumulation of compromise.

Josiah stood by a window, the fine linen of his robe stirring in a listless breeze. Below, the city pulsed with the ordinary commerce of a kingdom at peace. But his eyes saw what was not immediately visible: the subtle smoke of household shrines, the faint, sweet-rotten smell of incense offered to unnamed things in the shadowed valleys. The words of the scroll had drawn a map of a different Jerusalem, a city honeycombed with altars to other gods, a people holding its breath between Yahweh and convenience.

He tore his robe. It was not a dramatic gesture, but a slow, deliberate rending of fabric, a physical echo of the fracture he now felt in the world. The council around him—priests, officials, elders—fell into a silence that was heavier than noise.

“Go,” he said, his voice low but carrying to the corners of the chamber. “Inquire of the Lord. For we have not kept the word written here. Our fathers have not obeyed.”

The prophetess Huldah’s confirmation was a mercy laced with fire. Judgment was coming, she said, for the piled-up idolatry of generations. But because Josiah’s heart was tender, because he had humbled himself and torn his robes at the hearing of it, he would be gathered to his grave in peace before the calamity. It was a personal reprieve that felt like a sentence. He had time, but it was measured time, sand in an hourglass that had already been turned.

What followed was not merely a reformation, but an excavation. Josiah became a king-archaeologist of the soul, digging through the visible city to expose its hidden foundations.

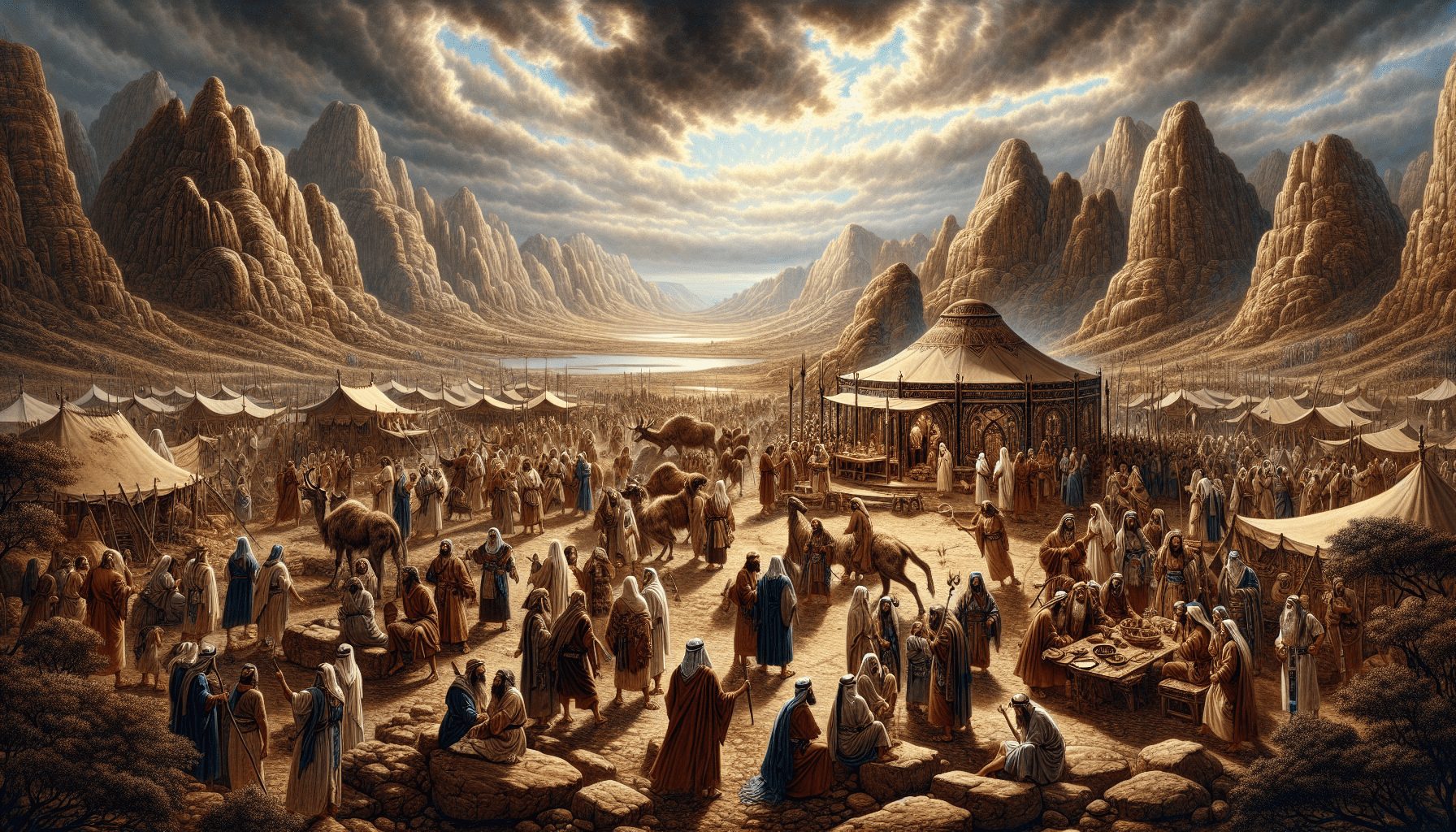

He called all the people to the Temple, from the grey-beards who remembered his grandfather Manasseh’s dark reign to the children who knew only the current peace. He read the words of the covenant aloud, his voice gaining strength as he stood in the court where the morning sun gilded the pillars. The people pledged themselves, a rustling, murmuring wave of assent. But Josiah knew pledges were wind without action.

He began in the Temple itself. It was not enough to have found the scroll there; the house had to be scrubbed clean. Out came the vessels made for Baal and Asherah and the “host of heaven,” forged in silver and gold during years when the kings of Judah thought it prudent to hedge their bets. The workmen, under the watchful eyes of the high priest Hilkiah, carried them into the Kidron Valley. Josiah himself went down. He watched as the precious metal was ground to powder, the wooden poles and carved images fed to a fire that spat greenish smoke. He took the dust from the idols and strewed it over the graves of the common people—a final, contemptuous burial.

But the infection had spread beyond the central sanctuary. He turned his gaze to the quarters of the city where the Temple’s shadow didn’t fall. In the very precincts of the Lord’s house, there were chambers where cult prostitutes had woven hangings for Asherah. He tore down the hangings, burned them, and dismissed the women, his face a mask of grim disgust. At the city gate where the judges sat, stood the horses and chariots dedicated to the sun-god by some long-dead king, a blasphemous fusion of Canaanite myth and royal power. He burned the chariots.

The purge rolled outward from Zion like a cleansing fire. He sent his officials north, to the towns of Samaria, to the shrines built by the kings of Israel that had outlasted the kingdom itself. At Bethel, where Jeroboam had set up a golden calf to keep his people from going south to Jerusalem, Josiah stood before the altar. He saw the tomb of the old prophet who had foretold this very day centuries before. “Leave that grave undisturbed,” he ordered, a strange moment of historical reverence in the midst of the wrecking. But the altar itself he broke apart, burning the Asherah pole that stood beside it, grinding the stones to lime dust.

Back in Jerusalem, the work grew more intimate, more terrible. He defiled the *Topheth* in the Valley of Hinnom, the place where the fire had burned for Molech and children had been passed through the flames. No more would that smoke rise. He removed the statues of horses at the entrance to the palace, symbols of solar worship, and burned the chariots of the sun. He looked up, to the roofs of the city’s houses where small altars to the stars smoked under the open sky, and had them broken down.

He was pulling up a nation by its roots. Priests of the high places, who had burned incense from Beersheba to Dan, were brought to Jerusalem. They were not killed, but stripped of their office, given a subsistence from the Temple offerings but barred from serving at the altar. It was a theological demotion, a quiet nullification.

And then, in the midst of this sweeping negation, he commanded a mighty affirmation. “Keep the Passover to the Lord your God,” he said, “as it is written in this Book of the Covenant.” It had not been kept like this, the chroniclers would later note, since the days of the Judges. The order went out. From the tribal lands of the south to the ravaged cities of the north he still controlled, the lambs were selected. On the appointed day, the priests and Levites stood in their divisions, following a liturgy rediscovered. The king himself provided from his own flocks and herds thirty thousand lambs and young goats, and three thousand cattle. The rulers followed his lead. The Levites, now centralised, roasted the Passover offerings for the common people who came in multitudes. The festival lasted seven days. The sound that filled Jerusalem was not the crackle of burning idols, but the singing of psalms, the bleating of flocks, the shared meals of families. The smell was of roast meat and unleavened bread, not incense of alienation.

When it was done, Josiah stood again on the palace height. The city was quiet, exhausted from celebration and purgation. He had uprooted, torn down, destroyed, and overthrown. And he had built and planted. The Law was no longer a scroll in a room, but a framework for the life of the city.

Yet Huldah’s words remained. The repentance was his, the heart was his. But the accumulated weight of centuries was a momentum not even a zealous king could fully arrest. He had cleaned the house, but the foundations had been shaken.

Years later, he would go out to meet Pharaoh Neco of Egypt at Megiddo, a strategic pass on the great coastal road. Neco, strangely, sent him a warning: “What have we to do with each other, king of Judah? I come not against you today, but against the house with which I am at war. God has commanded me to hurry. Cease opposing God, who is with me, lest he destroy you.”

Josiah disregarded it. Perhaps he saw any foreign army on the soil of the promised land as a threat to be confronted. Perhaps his decades of restoring what was pure made him unable to discern a more complicated political moment. He disguised himself and rode into the arcing storm of battle. A random arrow found a gap in his armor. His servants carried him from his chariot, dying, back to Jerusalem. They buried him in his own tomb, with the lament of all Judah and Jerusalem, and the singing of the dirge-singer Jeremiah.

The Passover lambs were forgotten. The ground-up dust of the idols, scattered on the graves, was trodden back into the earth. The high places, within a generation, would once more see faint tendrils of smoke curling into the twilight. He had been a righteous king, a rare flame burning in a gathering dusk. He had bought a lifetime of faithfulness for his people, a breathing space of grace. But the stones he had ground to powder were, in the end, only stone. The heart of the people, as the scroll had warned, was a harder substance, and its turning was a work for a different kind of king.