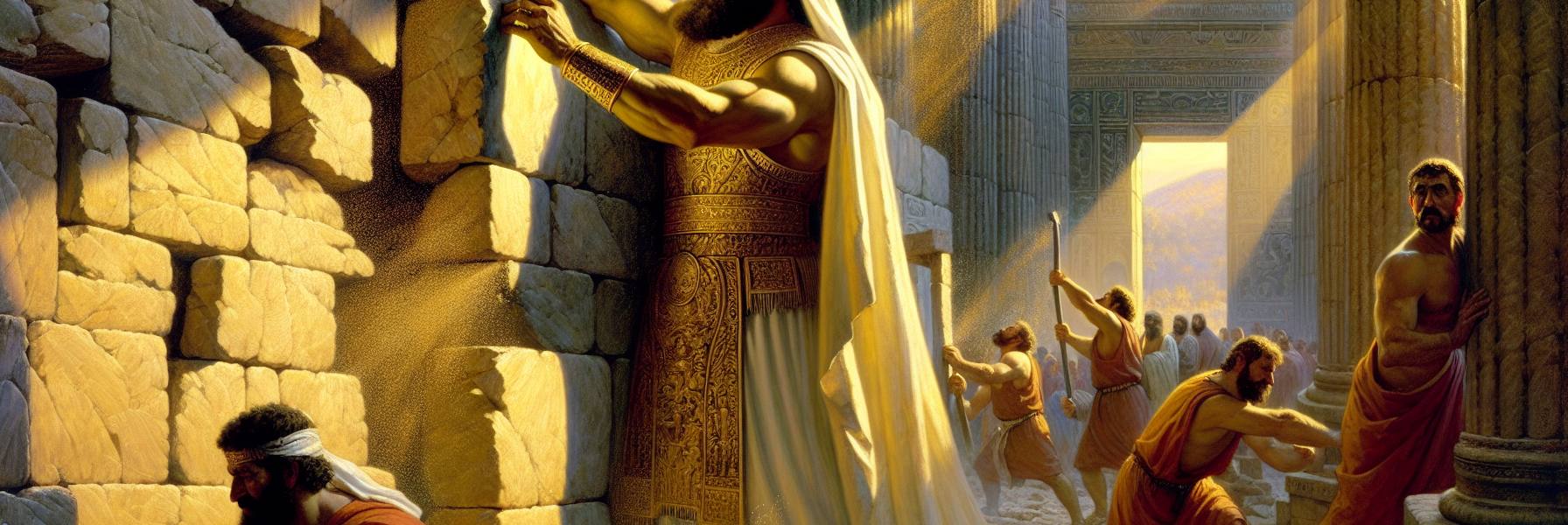

The stone dust hung in the air of the temple courtyard, a fine, golden haze in the late afternoon sun. It was the dust of renewal. Joash, king of Judah, watched as workmen, their forearms corded with muscle, fitted a new block of dressed limestone into the wall. The sound of chisels was a rhythmic, hopeful percussion. For years, the house of the Lord had languished—its walls cracked, its gold leaf tarnished, its gates splintered by weather and time. It had been a silent reproach.

He was seven years old when they crowned him, a small boy hidden in the temple itself while Athaliah’s bloody reign raged outside. He remembered the weight of the crown, cold and too large, and the warmer, firmer weight of Jehoiada the priest’s hand on his shoulder. That hand had guided him ever since. The priest, now ancient, his beard a cascade of white wool, stood beside him, leaning heavily on a staff. His eyes, clouded but still sharp, followed the work.

“It begins to look as it should,” Jehoiada said, his voice a dry rustle.

“It does,” Joash replied. But a worm of frustration turned in his gut. The work was slow, too slow. The Levites, sent out to collect the tax Moses had ordained for the tent of testimony, had returned with meager sums. The people, it seemed, had grown accustomed to neglect. Their piety, like the temple walls, had developed cracks.

“The chest,” Joash said suddenly, turning to the priest. “We will make a chest and set it outside, by the altar. A man will not give freely to a tax collector at his door, but if he brings his offering himself, to the very gate of the Lord’s house…” He let the idea hang.

Jehoiada considered it, then a slow smile broke across his weathered face. “The heart gives what the hand chooses to bring. Let it be so.”

They fashioned a chest of oak and banded it with iron. A hole was bored in its lid. They placed it in the court, and the proclamation went out across Judah and Jerusalem. The response was not immediate. For a day or two, the chest stood like a lonely sentinel. Then an old farmer, his sandals coated with road dust, came. He stood before it for a long moment, his face unreadable. Then he drew a small leather pouch from his belt, and the soft clink of silver echoed as the coins fell through the hole. It was a sound like a seed breaking open in good soil.

Others followed. The trickle became a stream. Merchants from the markets, their fingers stained with dye; widows with carefully hoarded mites; landowners with bulging sacks. The chest grew heavy. So heavy that when the king’s scribe and the high priest’s officer came to empty it, they had to call for a second pair of hands to tip it. They would count the money, stack it in neat piles, and hand it directly to the foremen of the work. The masons, the carpenters, the ironsmiths, all were paid honestly and without delay. The rhythm of the chisels quickened.

For years, the work continued under the watchful eyes of Jehoiada. The temple was restored to its original design, and strengthened. With the surplus, they made new vessels of gold and silver for the service. The burnt offerings were offered continually, morning and evening. There was a scent of cedar and fresh mortar, of incense and baking showbread. It was a good time. Joash, in those years, did what was right in the eyes of the Lord.

But time is a river that carves away even the hardest stone. Jehoiada grew very old, full of days, and died. They buried him among the kings in the City of David, a singular honor for a priest. The mourners were a multitude, and their lamentations were loud and genuine. Joash stood at the head of the procession, feeling a strange, hollow chill. The guiding hand was gone. The staff that had supported him was now just a piece of wood laid on a tomb.

It was after the funeral that the officials of Judah began to come to him. They were men of smooth words and polished beards, men who had chafed under the old priest’s strictures. They bowed low, but their eyes were calculating. “Your majesty,” they said, “the ways of Jehoiada were the ways of an older time. Let us serve you now. Let us worship as our fathers did before Solomon’s temple, at the high places and the sacred groves. It is simpler. It is… broader.”

And Joash, the king who had been a project of the priesthood, listened. The hollow space left by Jehoiada ached, and these men offered to fill it with their flattery and their convenient theologies. He gave his consent. The people, leaderless in spirit, soon abandoned the temple of the Lord. They worshipped Asherah poles and idols. The smoke from the high places began to cloud the Jerusalem sky once more.

Years passed. The new temple stood pristine, a monument to a faith its king no longer practiced. Then, a voice broke the spiritual silence. Zechariah, son of Jehoiada, now a priest himself, stood in the temple court his father had saved. He faced the king and the assembled people, his spirit stirred by God.

“Thus says God,” Zechariah’s voice rang out, clear and sharp as a trumpet blast. “Why do you transgress the commandments of the Lord, so that you cannot prosper? Because you have forsaken the Lord, He has forsaken you.”

The words hung in the air, a direct echo of the covenant. Joash felt them not as a correction, but as an insult. This was the boy he had known, the son of his guardian, now daring to rebuke him in his own courtyard. The officials around him murmured, their faces dark. The king’s own shame curdled into a hot, violent rage. He, who had rebuilt this very house, would not be lectured in it.

“Who gave him permission to speak thus?” Joash snarled. And then, a sentence born of pure, despicable ingratitude: “Kill him.”

They did not wait for shadows or a secret place. There, in the very court of the Lord’s house, between the altar and the sanctuary that Jehoiada’s faithfulness and Zechariah’s own father’s money had restored, they stoned him. The last thing Zechariah saw was the new, clean stonework. His blood, thick and dark, seeped into the joints between the stones as he died, gasping, “May the Lord see and avenge!”

The season turned. A small army of Arameans, not a great force but a marauding band, swept up from the south. They came against Judah and Jerusalem. They destroyed all the officials—those very men of smooth words—and sent their plunder to the king of Damascus. It was a surgical, humiliating strike. The Lord had seen.

Joash was left wounded, not in battle, but by his own servants who conspired against him for the blood of Zechariah. They murdered him on his bed. They did not bury him in the tombs of the kings, but in the City of David, separate. A quiet, dishonorable end.

The chronicler notes his reign, the early work, the chest, the restoration. But the final summary is stark: they killed him. And the temple, once filled with the sound of rebuilding, then with the sound of condemnation, and finally with the silence of abandonment, stood as a witness. It was a house repaired, but a covenant broken. The new stones held the memory of both the silver that bought them and the blood that defiled them, a silent testament to the fragile, terrifying gift of a second chance, and the cost of throwing it away.