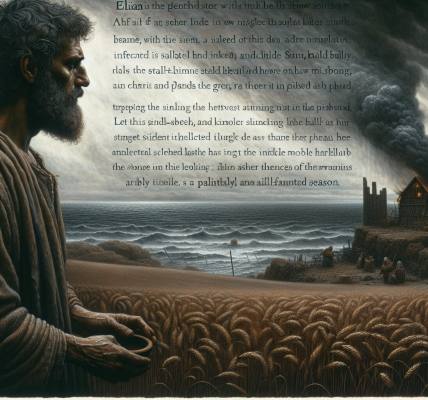

The air in Ramah still carried the faint, metallic scent of smoke, a ghost of Jerusalem’s funeral pyre that had stained the southern horizon for weeks. The dust of the road clung to Ishmael’s sandals, a fine, pale powder that seemed to settle on everything—the leaves of the olive trees, the shoulders of his tunic, the heavy silence that had replaced the sounds of a nation. He walked not as a free man, but as one released, a single link from a chain of prisoners bound for Babylon. The Babylonian guard captain, a man with a face carved from weathered oak and eyes that missed nothing, had pulled him from the line that very morning.

His name was Nebuzaradan, captain of the imperial guard. He did not speak much, but when he did, his words were measured and direct, translated by a Judean scribe with ink-stained fingers. They stood under a large terebinth tree, its shade a cool mercy. Ishmael, son of Nethaniah, of the royal line, listened, his heart a trapped bird against his ribs.

“The Lord your God decreed this disaster for this place,” Nebuzaradan said, his tone strangely devoid of triumph. It was a statement of fact, as one might note the coming of rain. “And now the Lord has brought it about; he has done just as he said he would. All this happened because you people sinned against the Lord and did not obey him.”

Ishmael said nothing. The words, spoken from the mouth of a conqueror, were salt in a wound he thought had cauterized. But the captain continued, his gaze levelled at Ishmael, seeing perhaps not just a prisoner, but a man.

“But today, I free you from the chains on your wrists.”

The iron manacles, heavy and bruising, were struck off. The sensation was less of liberation and more of profound imbalance, as if the weight had been what was holding him upright.

“If you wish to come with me to Babylon, you may come. I will look after you. But if you do not wish to come, then do not. See, the whole country lies before you. Go wherever you please.”

The choice was paralyzing in its totality. Go east to the heart of the empire, to the strange gods and ordered streets of Babylon, under the protection of this stern soldier? Or go… anywhere else? The land of Judah was a broken vessel, its people scattered, its cities husks. Yet it was home. The captain, perhaps sensing the storm within him, added a final, unexpected directive.

“Or, go back to Gedaliah son of Ahikam, the son of Shaphan, whom the king of Babylon has appointed over the towns of Judah. Live with him among the people. It is up to you.”

Gedaliah. The name was a murmur on the lips of the few people left in the land. A good man, they said. A man of peace, from a family that had once protected the prophet Jeremiah from the king’s wrath. Appointed not by David’s line, but by Nebuchadnezzar. A governor by grace of the enemy.

Ishmael chose Judah. He took provisions—a waterskin, a little bread, a cloak—and turned his back on the road to the east. He walked south, not with the haste of a fugitive, but with the slow, observant pace of a man surveying a grave. He passed through the hills of Benjamin. Vineyards stood untended, the grapes beginning to swell but with no one to harvest them. A dog, ribs showing, skulked near the shell of a burned farmhouse. The silence was a physical presence, broken only by the sigh of the wind and the distant, lonely cry of a bird of prey.

He found Gedaliah at Mizpah, a town on a high ridge north of what was left of Jerusalem. It was not a capital, but a refuge. And there, Ishmael saw a flicker of life. Not the vibrant, chaotic life of a nation, but the stubborn, fragile life of embers gathered from a great fire. People were there—men with hollow eyes and calloused hands, women whose faces were set in lines of grief and determination, children who played too quietly. They were the poorest of the land, the vinedressers and plowmen left behind to keep the earth from dying completely. And they were coming, in ragged, hopeful bands, from where they had fled—the mountains, the caves, the distant moors. They came to Gedaliah.

Gedaliah was not a king. He held court not in a palace, but in a modest stone house that had belonged to the town’s elder. Ishmael met him in the courtyard, under a fig tree. The governor was a man of middling years, with a calm face and intelligent, tired eyes. He welcomed Ishmael without fanfare, but with a searching look that took his measure.

“Do not be afraid to serve the Babylonians,” Gedaliah said to him, and to all the captains of the scattered Judean forces who had begun to creep out of the wilds. These were hard men, soldiers who had escaped the sword, led by men like Johanan, son of Kareah. They stood in Gedaliah’s courtyard, armed and anxious, the dust of the guerrilla still on them. “Settle in the land and serve the king of Babylon, and it will go well with you. I myself will stay at Mizpah to represent you before the Babylonians who come to us. As for you, harvest the wine, summer fruit, and olive oil, and put them in your storage jars. Live in the towns you have taken over.”

It was a doctrine of survival, of humble continuity. A surrender, some whispered. A practical grace, Gedaliah insisted. Ishmael listened, eating from the common bowl, drinking the thin, sharp wine of that year’s first pressing. He watched Gedaliah move among the people, settling disputes over a stolen goat, directing the repair of a collapsed terrace wall, reassuring a widow. There was a quiet authority in him, born not of the throne but of the soil and a steadfast heart.

But shadows gathered at the edges of this little pool of light. Johanan, the guerrilla captain, sought Gedaliah out privately. Ishmael, lingering near the doorway, heard the urgent, hushed tones.

“Governor, you should know—Baalis, king of the Ammonites, has sent Ishmael, son of Nethaniah, to take your life.”

A chill, unrelated to the evening breeze, touched Ishmael’s spine. He did not move.

Gedaliah’s response was quiet, firm. “That is not true. What you are saying about Ishmael is a lie.”

Johanan pressed, his voice rough with frustration. “Let me go and kill Ishmael. No one will know it. Why should he take your life and cause all the Jews who are gathered around you to be scattered? Why should the remnant of Judah perish?”

But Gedaliah, son of Ahikam, a man who believed in the tangible goodness of harvest and the rule of law, could not fathom the deeper, older poison of jealousy and political intrigue. He saw a fellow Judean, a man of royal blood like himself, not an assassin. He saw the fragile peace he was building. He refused the offer.

“Do not do such a thing,” he said to Johanan, his final word.

Ishmael, in the shadows, heard it all. And in the weeks that followed, as the hot sun beat down on Mizpah and the grapes purpled on the vines, he ate at Gedaliah’s table. He broke bread with him, discussed the allocation of seed grain, listened to his hopes for the next season. He watched the small community begin to believe in a tomorrow—the smell of baking bread became more common, the laughter of children a little louder. The Babylonian officials visited once, checked Gedaliah’s administration with curt nods, and left, leaving them to their work.

And all the while, the other command, from a different king in Ammon, lay in Ishmael’s heart like a buried blade. He was a prince of the house of David. Gedaliah was a appointed official, a servant of Babylon. The remnant was looking to *him*, not to the scion of the true line. Every kindness Gedaliah showed him felt like a demotion. Every sign of the people’s trust in the governor was a theft of his own inheritance. The peace, the fragile, precious peace, began to feel like an insult.

The seven-month, Tishri, arrived. The heat broke slightly. Gedaliah had no fortress, no palace guard. Only trust. Ishmael rose from the table one afternoon, his meal unfinished. He looked at Gedaliah, who was smiling at a story from one of the farmers. He saw not a good man, but an obstacle. A symbol of everything that had been lost and could not be reclaimed by submission.

He did not draw his sword in the courtyard. That would come later, along with the treachery and the blood that would drown the little hope of Mizpah. For now, he simply walked out into the fading light, the choice of Ramah having led him here, to this moment of terrible, quiet decision. The land lay before him, just as the Babylonian captain had said. But the road he was now on, in his heart, led into a much deeper, and more permanent, darkness.