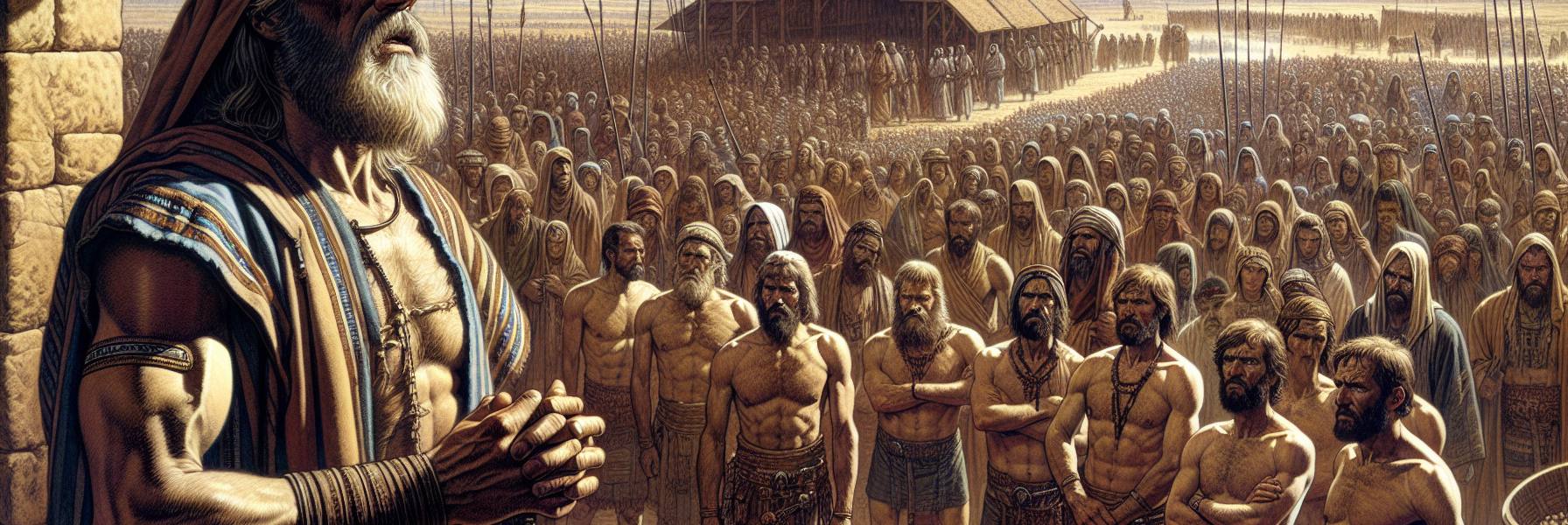

The dust of the Canaan campaign had finally begun to settle, not just on the land, but in the bones of the men who had fought for it. For the Reubenites, the Gadites, and the half-tribe of Manasseh, the time had come. Joshua, his face a map of sun-weathered lines and his eyes holding the quiet weight of witnessed miracles, summoned them to Shiloh. The Tabernacle stood there, a humble yet profound presence, a reminder of a promise that had marched with them through the desert and across a river held back by the hand of God.

He spoke to them with a blunt, soldier’s gratitude, acknowledging the years they had fought west of the Jordan, fulfilling their oath to their brothers while their own families and flocks waited in the lands Moses had granted them east of the river. “You have kept all that Moses commanded,” he said, the words simple but heavy with significance. “You have not forsaken your brothers these many days.” Now, he told them, they were released. They could go home.

But his blessing was laced with a father’s fierce admonition. He charged them to be meticulous—to love the Lord, walk in His ways, keep His commandments, hold fast to Him, and serve Him with all their heart and soul. It wasn’t just a farewell; it was an anchor line thrown across the Jordan, a plea for unity that transcended geography. With that, he blessed them and sent them away, their packs heavy with spoil, their minds lighter with the prospect of home.

They crossed the Jordan near Jericho, the river flowing normally now, just water over stones. But when they reached the Geliloth region on the eastern bank, right at the Jordan’s edge, they stopped. A resolve, sudden and collective, took hold of them. They began to gather stones—not for a fortress or a boundary marker, but for an altar. And not a small one. They built it massive, imposing, a structure of such scale that it could be seen from a great distance. It was, in its sheer physicality, a statement.

Word travels faster than a man on a horse when the news is troubling. The report flew to the assembly at Shiloh: the eastern tribes had built an altar, a rival altar, facing the land of Canaan. A cold dread seized the hearts of the western tribes. It wasn’t just disagreement; it was catastrophe. In their minds, there was only one altar, the one before the Tabernacle, the one ordained by God. To build another was to rebel, to invite the same wrath that had consumed Nadab and Abihu for offering strange fire, or the entire congregation at Peor for idolatry. The memory of Achan’s sin, which had cost thirty-six lives at Ai, was still a fresh scar. One man’s transgression had brought judgment on all. What would the sin of two and a half tribes bring?

The congregation gathered at Shiloh, not for celebration, but for war. They mobilized, ready to march east and bring their brothers to heel by force. But first, wisdom prevailed—just barely. They sent a delegation, led by Phinehas the priest, son of Eleazar, and ten chiefs, one from each western tribe. These were not ambassadors of peace, but investigators, their mission laced with ultimatum.

They found the eastern tribes by the great, enigmatic altar. The accusation Phinehas delivered was not a question, but a thundering indictment. He listed their presumed crimes: building a pagan altar, breaking faith with the God of Israel, turning away from Him. He invoked the sins of Peor and Achan, the lingering plague, the collective guilt. “If you rebel against the Lord today,” Phinehas said, his voice sharp as flint, “He will be angry with the whole congregation of Israel tomorrow.” The offer was stark: if their land east of the Jordan was unclean, then they should cross over and settle among their brothers. But do not rebel. Do not build an altar besides the Lord’s.

The silence that followed was thick, charged with the potential for violence. Then the heads of the eastern tribes—men whose names are lost to the emphasis of the moment—began to speak. Their reply was not defensive, but astonished, pained.

“The Mighty One, God, the Lord! The Mighty One, God, the Lord! He knows!” they cried out, invoking the divine name with a force that halted the western chiefs. “And let Israel itself know!”

They explained, their words tumbling out in a rush of earnest clarity. The altar was not for sacrifice. It was not for burnt offering or grain offering. They knew the law. They knew there was one place for sacrifice. The thought of turning from the Lord made them recoil in horror.

No, the altar was a witness. It was a replica, a testimony made of stone. Their fear was not of the gods of the land, but of the passage of time and the failing memories of men. They feared a future day when children on the west bank would look across the Jordan and say to the children on the east bank, “What have you to do with the Lord, the God of Israel? The Lord has made the Jordan a boundary between us and you. You have no portion in the Lord.” In that future day, their children might be cut off, perceived as foreigners to the covenant.

So they built the altar as a copy, a witness between them. It was a sign, a teaching tool for generations unborn. Its purpose was to proclaim, “Look! Our heritage is the same. Our God is the same. This altar says we serve the God whose altar is at Shiloh, even if we live beyond the river.” It was not a platform for sacrifice, but a podium for proclamation. It was a bridge of stone, built against the creeping tide of separation.

The explanation landed on Phinehas and the chiefs not as an argument to be won, but as a truth to be received. The heat of accusation dissipated, replaced by a profound, cool relief. Phinehas, the fiery priest who had once driven a spear through sin, now spoke with a different kind of strength. “Today we know that the Lord is in our midst,” he said, “because you have not committed this breach of faith against the Lord.” The war was averted. The misunderstanding was not just cleared up; it was transformed into a deeper understanding.

The delegation returned to Shiloh and reported. The news was good, and the people were satisfied. They praised God, and the talk of war ceased. The eastern tribes, for their part, named the altar. They called it *Witness*, declaring, “For it is a witness between us that the Lord is God.”

The story ends there, not with a grand celebration, but with a quiet, durable peace. It was a peace forged not in the absence of conflict, but in the hard, patient work of seeking understanding before drawing swords. It was a lesson that unity isn’t uniformity, and that faith sometimes requires building visible, tangible reminders against the invisible drift of the human heart. The altar by the Jordan stood, not for worship, but as a silent, steadfast sermon in stone, a declaration that the God of Israel was Lord of both banks, and that His people, though separated by a river, were bound by a promise.