The air in the chamber was still, thick with the smell of old scrolls and dust motes dancing in a single, slanted shaft of late afternoon light. Zechariah, son of Berechiah, son of Iddo, felt the weight of the silence. It was the eighth month, in the second year of Darius. Outside, Jerusalem was a skeleton—a place of broken stones and stubborn hope. The returned exiles had laid the temple foundation years ago, and then… nothing. The work had faltered, swallowed by hardship and a creeping resignation.

He wasn’t a man given to dramatic visions. He was a priest, a returner, a man who knew the gritty reality of mixing mortar and fending off doubt. But that day, a word settled on him—not with thunder, but with the unsettling clarity of a cold drop of water on the neck. It was a burden, a heavy message he was to carry. The Lord was profoundly displeased. Not in a raging, fire-from-heaven way, but with the weary disappointment of a father whose children had forgotten the sound of his voice.

“Your fathers,” the word came, “where are they?” It wasn’t a question about genealogy. It was a knife twisting in the collective memory. The prophets—they had cried out, warned, pleaded. ‘Turn from your evil ways, your evil deeds.’ But the ancestors had shrugged, turned away, and now they were dust. And the words of those prophets? They had overtaken them, tracked them down like hounds. The exile had proved the warnings true.

Zechariah spoke this to the people, his voice scratchy from the dust. “The Lord of hosts says to you: Return to me… and I will return to you.” It was the old, unbreakable covenant, cracked open again. Do not be like your fathers, he urged. They are gone. Their choices are their own. Yours are now.

The people listened. In their eyes, he saw the flicker of something old and good—recognition, perhaps, or a long-buried fear of the Lord. It was a start.

Then, on the twenty-fourth day of the eleventh month—the month of Shebat, when the almond trees in the hills were just thinking of blooming—the experience shifted. The world of stone and mortar and hesitant hearts dissolved.

It was night, but not any night he knew. He found himself in a glen, shadowy and deep. Among the myrtle trees, their dark, glossy leaves soaking up the faint light, stood a man. No, not a man. A figure astride a red horse. He was poised, still, as if waiting. Behind him, lost in the deeper shadows under the trees, were more horses—red, sorrel, white. Their breath made no steam in the cool air; they were statues of living muscle and intent.

His mind reeled. “What are these, my lord?” The question escaped him, whispered to the angel who was now suddenly talking with him, a presence he felt more than saw.

The angel’s reply was calm, instructional. “I will show you what they are.”

Then the man among the myrtles, the rider on the red horse, spoke. His voice was like the sound of many waters under the earth. “We have patrolled the earth, and behold, all the earth remains at rest.” It was a report. Military. Celestial.

And then another voice—older, deeper, woven into the fabric of the shadows and the starlight above the myrtles. The Lord himself. “O Lord of hosts, how long will you have no mercy on Jerusalem and the cities of Judah, against which you have been angry these seventy years?”

Seventy years. A lifetime. A complete span of desolation.

The angel who talked with Zechariah turned to him, and in that turn was a profound comfort. He spoke, not to the divine council, but to Zechariah the priest, Zechariah the bewildered man. “Thus says the Lord of hosts: I am exceedingly jealous for Jerusalem and for Zion. And I am exceedingly angry with the nations that are at ease.”

He understood then. The patrol, the report of a world at rest—it was not peace. It was complacency. While Zion lay in ruins, the nations that had been the rod of God’s discipline were now fat and comfortable, adding their own cruelty to His righteous judgment. Their ease was an offense.

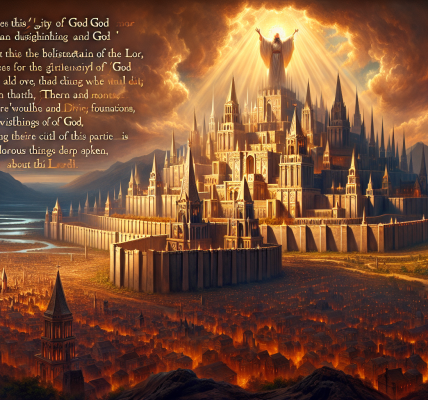

The voice of the Lord continued, warming now, like the first sun on a frosty field. “Therefore, thus says the Lord, I have returned to Jerusalem with mercy; my house shall be built in it… and the measuring line shall be stretched out over Jerusalem.”

The vision deepened, layered. The angel told him to proclaim it: The cities of Judah would overflow with prosperity. The Lord would again comfort Zion and choose Jerusalem. A filament of future glory, woven into the present despair.

Then the myrtle glen was gone. He saw four horns—not animal horns, but symbols of brutal, crushing power, the horns of the nations that had scattered Judah. And immediately, four craftsmen appeared. Not warriors, but artificers, men with tools. “These have come to terrify them, to cast down the horns of the nations who lifted up their horns against the land of Judah to scatter it.”

The message was relentless, beautiful, and terrifying. Judgment was not a singular event in the past. It was a process. The instruments of punishment would themselves be broken by other instruments, raised by God. Nothing was outside the weave.

Zechariah awoke, if that was the word for it, back in his chamber. The shaft of light had moved. The dust motes still danced. But everything was different. The silence now was not empty; it was charged, like the air before a summer rain. The broken stones outside were no longer just a monument to failure. They were a promise, awaiting the measuring line.

He picked up his stylus. His hand trembled, not with fear, but with the profound weight of what had been seen and heard. The word of the Lord was not a relic. It was a living thing, patrolling the earth, reading the hearts of nations, speaking in the gloom of myrtle thickets. And it had, for reasons he would never fully comprehend, spoken to him. The rebuilding would not just be of stone and cedar. It would begin here, in the quiet, recalibrated heart of a man who had seen the horses standing in the shadows, waiting for the command to move.