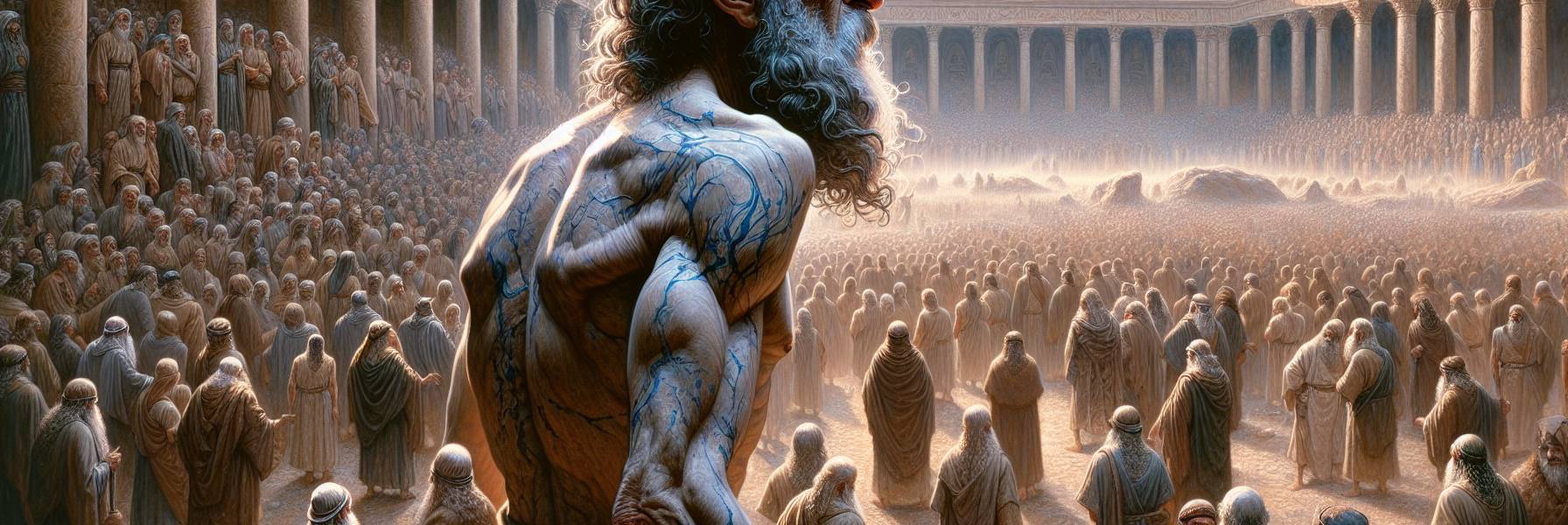

The air in the assembly ground at Shechem held the dry, dusty weight of years. It was not the cool, damp breath of the Jordan valley, nor the salty sting of the coast, but the settled breath of the heartland, smelling of crushed thyme and old stone. Joshua, son of Nun, stood before them. He did not stand as he once had—a blade of a man, straight and sure. Now, he was a gnarled olive tree, his back a gentle curve, his hands mapped with rivers of blue vein and valleys of scar. The sun, lowering towards the western hills, lit the silver in his beard and the deep seams around his eyes—eyes that had seen Jericho’s walls become dust and Ai’s kings hang from trees.

They had gathered, all Israel: elders, heads, judges, and officers. They came not at the blast of a war horn, but at the quiet, solemn summons of a fading voice. They sat on the ground, the fabric of their cloaks a tapestry of earthy browns and worn blues, their faces turned upwards, expectant, uneasy. They knew this was not a council for planning battles. The land, for now, had rest.

Joshua’s voice, when it came, was not the thunderous shout that had echoed at Gibeon. It was thinner, weathered, but it carried with a terrible clarity, like a clean crack in dry wood. He did not begin with formalities.

“You have seen,” he said, the words falling slowly, deliberately, “all that the Lord your God has done to all these nations for your sake. It was not your sword that did it. It was not your bow.”

He paused, letting the memory settle over them—the panic sent into Canaanite camps, the hailstones at Azekah, the sun standing still. A donkey brayed in the distance, a mundane sound against the backdrop of sacred history.

“I have allotted to you these nations that remain as an inheritance for your tribes,” he continued, his hand making a slow, sweeping gesture towards the hills, “all the nations I have cut off, from the Jordan to the Great Sea in the west. And the Lord your God, He will push them out from before you and drive them from your sight. And you shall possess their land, just as the Lord your God promised you.”

A murmur, hopeful and proud, rippled through some. Joshua’s eyes, however, held no triumph. They were the eyes of a man reading a familiar, frightening text written on the horizon.

“Therefore,” he said, and the word was a hinge, turning the narrative from past grace to future peril, “be very strong to keep and to do all that is written in the Book of the Law of Moses, turning aside from it neither to the right hand nor to the left. Do not mix with these nations that remain among you. Do not utter the names of their gods. Do not swear by them. Do not serve them. Do not bow down to them.”

He leaned forward slightly, the movement costing him effort. “But you shall cling to the Lord your God, as you have done to this day. For the Lord has driven out before you great and strong nations. And as for you, no man has been able to stand before you to this day. One man of you puts to flight a thousand, since it is the Lord your God who fights for you, just as He promised.”

He then did something that stilled the last whisper among them. He stopped speaking about their strength and began to speak of his own end. “And now, behold, I am about to go the way of all the earth.” The phrase, “the way of all the earth,” was ancient, dusty, final. It acknowledged the common dust from which they all came and to which they all returned. “And you know in your hearts and in your souls, all of you, that not one word has failed of all the good things that the Lord your God promised concerning you. All have come to pass for you. Not one word of it has failed.”

The assurance was breathtaking, a monumental credit to divine faithfulness. Yet Joshua immediately pivoted, using that very faithfulness as the foundation for a warning. “But just as all the good things that the Lord your God promised concerning you have come upon you, so the Lord will bring upon you all the evil things, until He has destroyed you from off this good land that the Lord your God has given you, if you transgress the covenant of the Lord your God, which He commanded you, and go and serve other gods and bow down to them.”

The sun was a half-dome of fire on the hilltops now, casting long, distorted shadows that seemed to stretch like dark fingers towards the people. Joshua’s shadow was a giant, trembling against the slope.

“Then the anger of the Lord will be kindled against you,” he said, and the word ‘kindled’ evoked a small, greedy flame catching on dry tinder, “and you shall perish quickly from off the good land He has given you.”

Silence. A profound, swallowing silence, broken only by the cry of a circling hawk. In that silence, the good land—the vineyards they did not plant, the cities they did not build—suddenly felt precarious, a gift held on a conditional lease. The covenant was not a relic; it was a living, breathing boundary. Joshua, the dying steward, was handing them the deed, and with it, the terrifying responsibility of their own fidelity.

He looked at them, this generation that knew war but was learning peace. He saw the complacency already creeping in, the subtle allure of the nearby shrines on the high places, the practical temptations of treaty and intermarriage. His final words were not a blessing, but a solemn witness.

“You are witnesses for yourselves. You have chosen for yourselves the Lord, to serve Him.”

They shifted, uncomfortable. The choice, made at Sinai and renewed here, was being placed back in their hands, daily, hourly.

“And they said, ‘We are witnesses,’” Joshua echoed, recalling their past vow. “Then put away the foreign gods that are among you,” he implored, his voice gaining a final, gravelly strength, “and incline your heart to the Lord, the God of Israel.”

The assembly was over. He turned, leaning on a young attendant, and began the slow walk away from the assembly ground, towards his own inheritance in Timnath-serah. The people rose, but they did not disperse quickly. They stood in small groups, speaking in low tones, the brilliant sunset now feeling more like a warning conflagration than a blessing. The words of the old man hung in the twilight air, as tangible as the coming chill. They were no longer following a pillar of cloud or fire. They were walking into a future where the only sign would be the condition of their own hearts, and the only sound of battle would be the quiet, relentless war against the idols within.