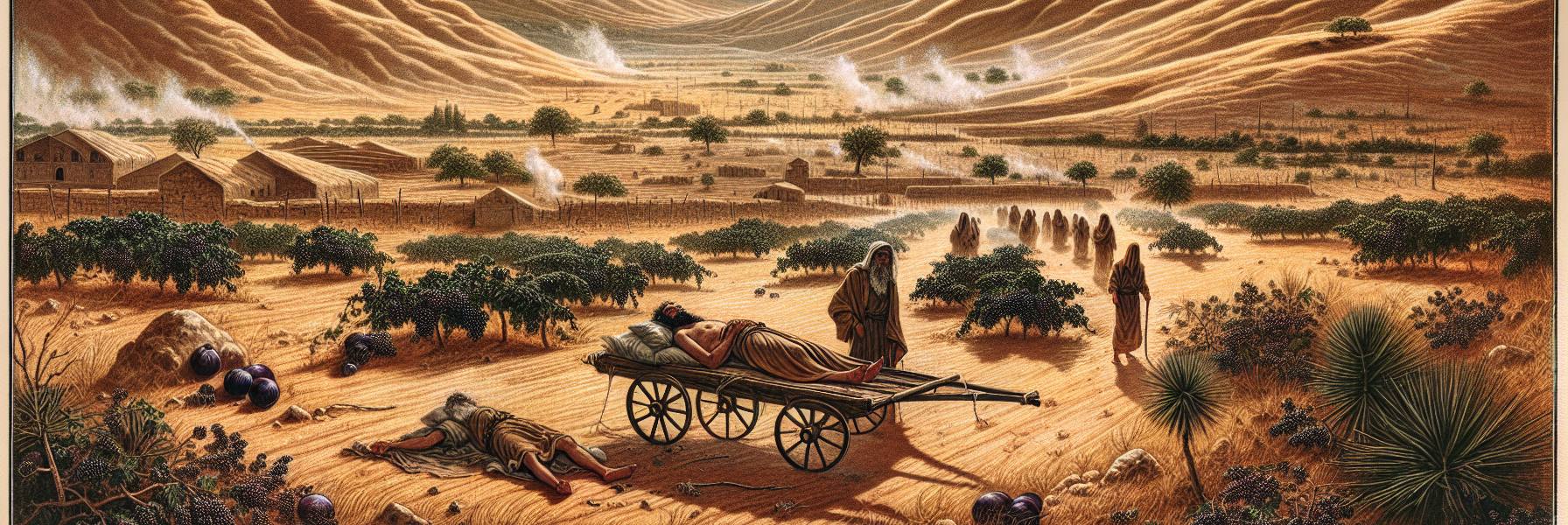

The heat in Judah that year was a physical presence. It lay upon the land like a heavy wool blanket, pressing the scent of parched thyme and cracked earth into every crevice. In the hill country, the terraces that usually cradled verdant rows of grapes and olives now held only dust, which lifted in lazy, golden ghosts at the slightest movement. Amariah, a man whose shoulders remembered the weight of many harvests, leaned on his digging stick and looked out over his field. The figs had shriveled on the branch, blackened little hearts. The well, he knew, was little more than a damp hole.

He heard the chatter before he saw the procession. A litter, borne by four sweating servants, emerged from the road that led from Jerusalem. Upon it, reclining in the scant shade of a linen canopy, was Micah, a royal official. His robes were fine, if travel-stained, and a gold seal-ring caught the relentless sun. He was speaking loudly to his scribe, a young man whose stylus hovered anxiously over a wax tablet.

“…and the king’s assessment must reflect the stability of the region,” Micah was saying, his voice carrying in the still air. “Order is maintained. Commerce, while slowed by this… inconvenience, continues. The report will speak of resilience.”

Amariah wiped the grit from his brow. Resilience. He watched the official’s eyes sweep over his dying field without seeing it, seeing instead a column of numbers, a tribute to be logged. This man, Amariah thought, was like the false shelters the shepherds built in the high pastures—structures that looked adequate from a distance but offered no real shade from the noon sun, no true barrier against the night’s wind. He called out nobility, but his words were hollow. He pronounced judgment on petty thieves in the market, yet his own decrees stripped the poor of their last measure of grain. He was a cloud promising rain, passing over with only a whisper of shadow.

That night, in the city, the atmosphere was different but no less stifling. In the house of a wealthy merchant, a party was underway. Lamps smoked, casting a dancing glow on faces slick with oil and sweat. Wine, imported from Egypt at great cost, flowed. A musician plucked a desultory tune on a lyre, the sound barely rising above the talk of deals and alliances. Shamar, the host, raised his cup. “To our understanding,” he boomed. “While the foolish worry about the sky, we secure the foundations of the earth!” Laughter rippled, uneasy. There was a brittleness to the merriment, a frantic edge. The women, their bangles clinking, spoke of new linens, but their eyes kept flicking to the shuttered windows, as if expecting to see the gaze of the wilderness pressing in. They celebrated a harvest that had not come, relying on stored wealth that was, day by day, becoming mere pottery tokens of a reality that was slipping away.

Amariah, having come to the city to barter a last pair of doves for salt, witnessed this from the street. He saw the lit windows, heard the muffled laughter. He thought of the prophet’s words, muttered in the gate by the few who still listened: *Woe to those who are at ease in Zion…* This was not ease, he realized. It was a stupor. A deliberate numbing. They were calling evil good, and good evil. The fool was called noble, and the noble heart was dismissed as a fool’s dream.

Then, the change began. It did not come with trumpets, but with a silence.

It was the silence of the wind dropping entirely. The silence of the official Micah, found one morning staring at an empty treasury ledger, his clever phrases dried up on his tongue, his ring feeling like a weight of cold metal. The spirit of confusion, like a desert sirocco, swept through the halls of power. Counselors offered plans that led in circles; the wise old men found their proverbs suddenly empty, their wisdom revealed as mere tradition without understanding. The women in the fine houses found their larders were full, but their hearts were a cavern of fear. The vines they had clung to—security, status, luxury—were exposed as shallow roots in shallow soil.

The breaking point was a day of no rain, but of a different kind of storm. A rumor, a panic at the gate, a realization that the walls they had trusted in were only as strong as the justice of the men who manned them. And that justice had been sold for summer fruit and soft garments. The city, for all its noise, became like a barren field, a joyous city forsaken.

But in the silence that followed the crumbling, a different sound was heard. Not in the palace, but in the streets where the poor gathered. Not in the council chambers, but in the home of a woodcarver named Eliab, who had little but a steady hand and a quiet spirit.

It began with a act so simple it was revolutionary. Eliab saw his neighbor, a widow, struggling to mend her roof before the (hoped-for) rains. He laid down his own work, climbed up, and fixed it. He asked for nothing. In the marketplace, when a farmer from the hills—it was Amariah—came with his doves and was offered a pittance by a trader, a grain merchant named Tobias spoke up. “That is not a fair price,” he said, his voice clear in the haggling din. “Give him what the doves are worth, or I will not sell to you either.” The trader, shocked, complied.

This was the spirit being poured out from on high. Not with spectacle, but with substance. The righteous man, Eliab, was not a king. But in his lane, he executed justice. The merchant, Tobias, was not a judge. But in the gate, he defended the cause of the poor. It was as if a long-dormant seed, buried deep beneath the hardened soil of the land, had finally felt a hint of moisture and stirred.

Amariah returned to his hills. The sky was still hard and blue, but something had shifted. He worked, not with the desperation of before, but with a patient diligence. He rebuilt a terrace wall that had collapsed. He shared his last handful of seed grain with the family next door. He spoke plainly, his words true and direct, no longer the convoluted bargains of the past. He was a shelter, a true one. Not a grand palace, but like the great rock overhang on the north side of his property—a place of real refuge from the storm, of durable shade.

And then, the rain came.

It did not come as a deluge, but as a soft, steady, soaking rain that fell for a day and a night. Amariah stood at the door of his house, feeling the cool, fragrant air wash over him. He could almost hear the earth drinking, a deep, sighing whisper. The wilderness, in his heart and in the land, began to recede. What had been a haunt of jackals—of desperation, fear, and scarcity—began to transform. Not all at once. But the field, he knew, would now bear fruit. Not just figs and grapes, but justice, and peace.

The work of righteousness would be peace, he understood now, standing in the gentle rain. And the effect of righteousness, quietness and trust forever. His people would dwell in a peaceful habitation, in secure dwellings, in quiet resting places. It would not be because a king on a throne decreed it, but because a woodcarver fixed a roof, a merchant spoke a true word, and a farmer shared his seed. It was the fruit of a right spirit, finally taking root in the broken-up soil of their hearts. And as the rain fell, washing the dust from the leaves of the few remaining olives, it seemed to him a promise of a goodness as deep and as wide as the heavens themselves.