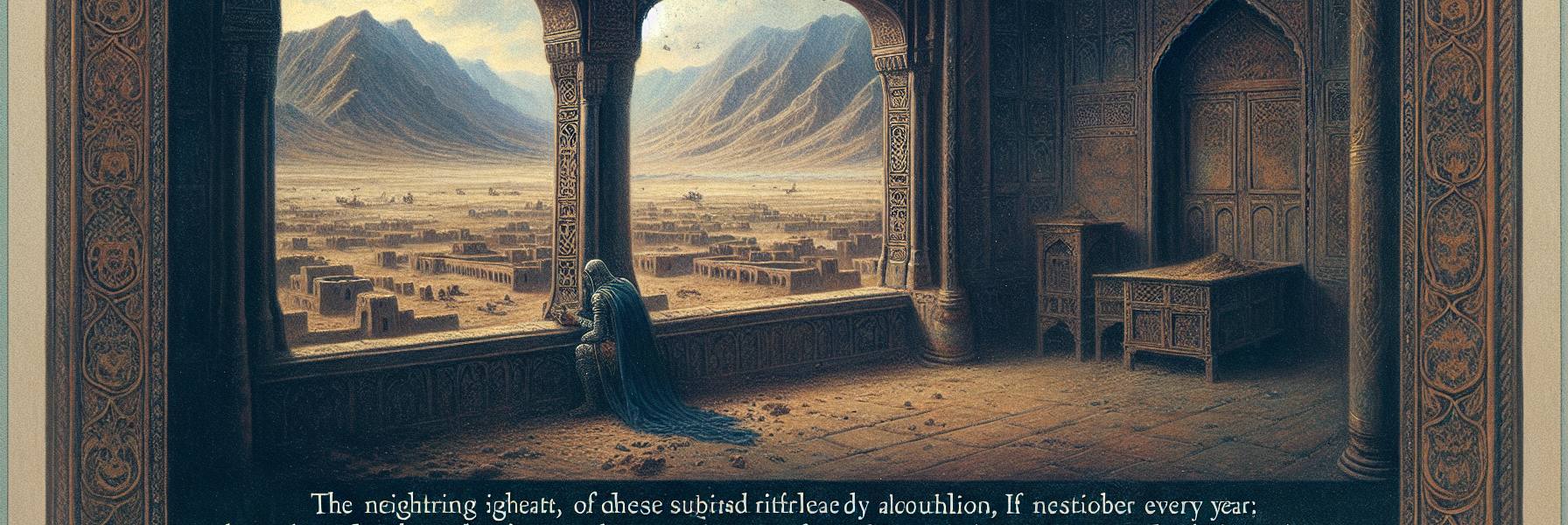

The air in Samaria tasted of dust and defeat. It was a taste King Jehoahaz had known for most of his seventeen-year reign, a fine powder that settled on the tongue and hinted at barren fields and empty storehouses. He stood at a narrow window in the palace, looking not at the hills of his inheritance, but inward, at the slow decay of his soul and his kingdom. Hazael, king of Aram, was a constant pressure, a vise tightening year by year. His son Ben-Hadad continued the cruelty, his raiding parties leaving Israel’s towns as skeletal as the stripped carcasses left in the sun. The army of Jehoahaz, once a formidable force, had been whittled down to a pitiful remnant: fifty horsemen, ten chariots, ten thousand foot soldiers—a laughable force against the Aramean tide. It was the slow, grinding judgment Yahweh had sent for the sins of Jeroboam, the calf-idols at Dan and Bethel whose gilt seemed to mock their impotence.

But pain, sometimes, turns the heart. Not in a grand, sweeping repentance, but in a desperate, guttural cry. Jehoahaz, in the quiet of his chamber, the taste of dust in his mouth, *sought the Lord’s favor*. The scriptures are sparse here, but one can imagine the scene: not a polished prayer, but the ragged plea of a cornered man. The pressure was too great. And Yahweh, whose ears are tuned to the frequency of anguish, listened. Not because of the king’s merit, but because of His own covenant, because of the ancestors, because He could not bear to see the name of Israel utterly blotted out just yet. The text says He gave Israel a deliverer. It’s a mysterious phrase. Perhaps a military leader arose, a flash of forgotten valor. Or perhaps it was a respite, a shifting of Aram’s attention elsewhere, a breathing space. The vise loosened, just enough for the people to dwell again in their own homes, but the foot of Aram remained on their neck. They did not turn from the sins of Jeroboam; the Asherah pole even remained standing in Samaria. The deliverance was a mercy, not an endorsement.

Jehoahaz slept with his fathers, and they buried him in Samaria. His son Joash—not the Judahite king of the same name, but a northern shadow—took the throne. He reigned sixteen years in Samaria, and he too did evil, walking steadfastly in the old, bad path. The theological record is blunt. Yet, within this relentless continuity of failure, a strange and tender encounter unfolds.

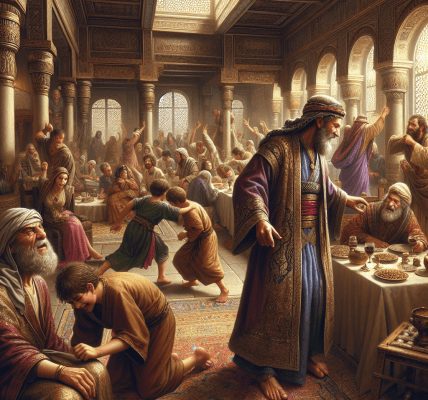

The prophet Elisha was dying. The man who had purified Jericho’s spring, multiplied a widow’s oil, raised a Shunammite boy from death, and humbled an Aramean army with blindness, was now confined to his bed, his breath shallow. The news reached King Joash. Perhaps some spark of memory, some latent respect for the sacred, moved him. He came down to the prophet’s house and wept over him, his face hovering above the old man’s. “My father, my father!” he cried. “The chariots of Israel and its horsemen!” It was the very cry Elisha himself had uttered as Elijah was taken. It was an acknowledgement that this fading old man was a stronger defense than all his pitiful troops.

Elisha, mustering the last of his prophetic fire, gave instructions. “Take a bow and some arrows.” The king complied, fetching a war bow and a quiver. “Put your hand on the bow,” Elisha said. His own hands, thin and trembling, then came to rest over the king’s hands, a transmission of waning strength to faltering royalty. It was a sacrament of war.

“Now open the east window,” Elisha whispered. Joash pushed the lattice open. The view would have been toward the Transjordan, the direction from which Aram’s threat always came. “Shoot!” And Joash drew the bow and shot. At that moment, the prophet’s voice, though frail, rang with a sharp authority. “That is the Lord’s arrow of victory, the arrow of victory over Aram! You will completely defeat the Arameans at Aphek.”

Then came the second act, the test of the king’s zeal. “Take the arrows,” Elisha said. Joash gathered them. “Strike the ground with them.” The king took the arrows and struck the ground. Once. Twice. Three times. And then he stopped. He stood there, the arrows in his hand, looking perhaps at the prophet, perhaps at the floor.

The old man’s anger was a sudden, hot thing in the quiet room. “You should have struck five or six times!” he exclaimed, his voice cracking with a fierce disappointment. “Then you would have defeated Aram and completely destroyed it. But now you will defeat it only three times.”

The moment hangs there, heavy with lost potential. Joash’s action was perfunctory, half-hearted. It revealed a limited imagination, a small faith. He performed the ritual but lacked the hunger for total deliverance. His victory would be partial, a check, not a conquest. The mercy of God would work within the confines of the king’s own spiritual poverty.

Elisha died, and they buried him. The year rolled on. Bands of Moabite raiders, those perennial scavengers of Israel’s weakness, were marauding in the land. It was spring, the time when kings go to war, but also a time of mundane sorrow. A funeral procession for a dead Israelite man was startled by one of these raiding bands. In haste, the mourners did a shocking thing: they threw the man’s body into the nearest tomb, which happened to be the cave of Elisha. The moment the dead man’s body touched the bones of Elisha, he came to life, springing to his feet. It is a bizarre, almost intrusive miracle, tucked at the end of the chapter like a postscript. No explanation is given. It serves as a final, potent testimony that the word and power of Yahweh, mediated through His prophet, were not extinguished by death. Life was still possible, even for a nation entombed in its own disobedience.

And King Joash? He fought Ben-Hadad three times, as Elisha had said, and recaptured the cities of Israel that his father had lost. The grip of Aram loosened a little more. But the floor of the palace in Samaria, where he had struck the ground three times with those arrows, became a silent monument to the victory that could have been—a complete restoration forever forfeited by a half-hearted king. The dust of Samaria still tasted of mercy, but it was a mercy mixed with the grit of missed opportunity, a story of God’s faithfulness persisting stubbornly in the soil of human failure.