The heat of the month of Nisan was beginning to thicken the air over Jerusalem, a dry warmth that promised the coming furnace of summer. In the courtyards of the Temple, a different kind of heat was building—the controlled chaos of ten thousand men preparing for a Passover unlike any seen since the days of the prophet Samuel. King Josiah felt the weight of it, a physical pressure on his shoulders beneath the linen robe. It was not just the weight of the crown, but the weight of the scroll, the words of the Law found in the rubble of the neglected Temple, now burning in his mind like the coals on the altar.

He moved through the priests, the Levites, a figure of calm insistence. His voice, hoarse from days of instruction, cut through the lowing of cattle and the bleating of sheep. “The lambs are to be without blemish,” he said again, not to a chief priest, but to a young Levite whose hands trembled as he checked a yearling’s hoof. “Look at the eyes. Clear. Always the eyes.” The boy nodded, swallowing hard, and Josiah moved on.

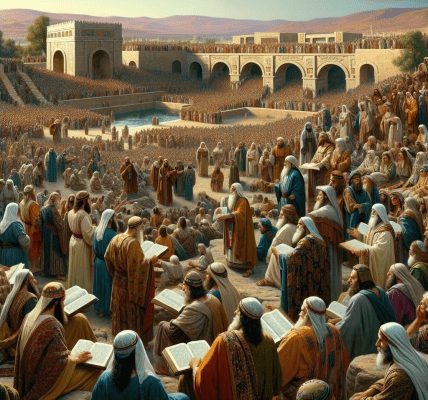

He had given freely from his own flocks—thirty thousand sheep and goats, three thousand cattle. The numbers were staggering, but in the stone pen, they were just animals, dusty and confused, smelling of dung and dry hay. The nobility had followed, somewhat shamed into generosity: Conaniah and his brothers Shemaiah and Nethanel, the chiefs Hashabiah, Jeiel, and Jozabad. Their contributions were stacked in heaps: flour, oil, wine, the practical elements of a feast for a nation. Josiah watched a line of porters, muscles straining, bringing the king’s own contribution of Passover animals to the priests. There was a sacred economy to it, a flow of life and substance from the throne to the altar to the people.

The Levites, for once, were not merely keepers of the gates or singers. Josiah had reorganized them according to their ancestral houses, as the scroll dictated. They were to be mobile, holy butchers, swift and clean, for the people were many, and the ritual could not stall. He saw Pashhur and Meshullam, their robes tucked into their belts, knives being sharpened on stones with a rhythmic, grating sound. They moved with a focused urgency. They would slaughter the Passover lambs, dash the blood against the altar, and then pass the carcasses to their brethren to be skinned and portioned. Other Levites ran with ceramic pots full of blood, their bare feet slapping on the sun-warmed stone, their faces splattered.

The air grew heavy with the iron scent of blood and the rich, greasy smell of burning fat. The altar fire, fed continuously, roared and crackled, its smoke a dark column twisting into the pale blue sky. The priests, their linen garments stained crimson at the hem, worked in shifts, flinging fat onto the flames, the sizzle and pop a constant percussion under the chorus of Levitical singing. The singers—Asaph, Heman, Jeduthun—their voices were not the usual serene tapestry of praise, but something louder, raw, straining to be heard over the din. It was a sound of collective effort, of a people straining to remember a rhythm of worship long forgotten.

Josiah himself, shedding his royal outer robe, took up a position among them. He did not slaughter an animal, but he served. He carried a heavy basin of flour mixed with oil, the griddle-cake offering for the people clustered by family groups. His hands, usually reserved for the scepter and the scroll, were dusty with fine flour. Sweat traced lines through the powder on his forearms. He looked into the faces of his people—farmers from the hills of Judah, potters from the city, widows with children clinging to their skirts. They received their portions with awe, not just at the food, but at the sight of their king, his authority momentarily submerged in service. It was, he felt in his bones, the heart of the thing: the king as the chief servant of the covenant.

The work went on from morning until deep twilight, a relentless, sacred labor. When the last of the lambs was roasted, the last of the blood dashed, the last of the Hallel psalms sung, a profound exhaustion settled over the mount. But it was a clean exhaustion. The people ate where they were, in the Temple courts, in the spaces of the city, the shared meal a silent, solemn seal on the day. For Josiah, eating the bitter herbs and unleavened bread tasted like truth. It tasted like obedience. It was the culmination of his life’s work: the purging of the high places, the shattering of Asherah poles, the restoration of this broken, beautiful house. This Passover was a national reset, a wrenching of the calendar back to zero.

He would think of that taste weeks later, on the plain of Megiddo. The memory of the smoke and the singing would feel like a dream as he stood in his chariot, the Egyptian army arrayed like a bronze flood before him. Neco, the Pharaoh, had warned him. “I have no quarrel with you, Judah. My war is with Carchemish, far to the north. God has commanded my speed. Do not interfere with God.”

Josiah had not listened. Perhaps the zeal that fueled the reform had curdled into a certainty that blurred into arrogance. Perhaps he could not abide any foreign power, even on a harmless march, crossing the land he had purified. He disguised himself, a strange and futile gesture. A chance arrow, shot into the mass of chariots, found a gap in his armor. The pain was cold, then hot. They brought him from his chariot, his life bleeding out into the dust of the caravan route.

As they carried him back toward Jerusalem, the jolting of the cart was agony. The smells were different here: dust, blood, the sweat of men and horses. No altar smoke. No singing. He thought of the Levites, their knives, the flawless lambs. He thought of the scroll, and the promises, and the curses. He had done everything right. He had restored the Passover. And yet here he was, dying on a road God had told him not to take. The covenant was just, but its outcomes were inscrutable, woven on a loom he could not see.

They buried him in the tombs of his fathers. The city wept, a louder, more desperate sound than the singing in the courts. Jeremiah, the young prophet who had watched the reform with hopeful eyes, composed a lament. They sang it for generations, a haunting counter-melody to the story of the great Passover. And the people, who had eaten the lamb and tasted the obedience, knew that the memory of Josiah was like the Passover itself—a moment of perfect alignment, brilliantly clear, devastatingly brief, and impossible to hold onto as the world, relentlessly, moved on.