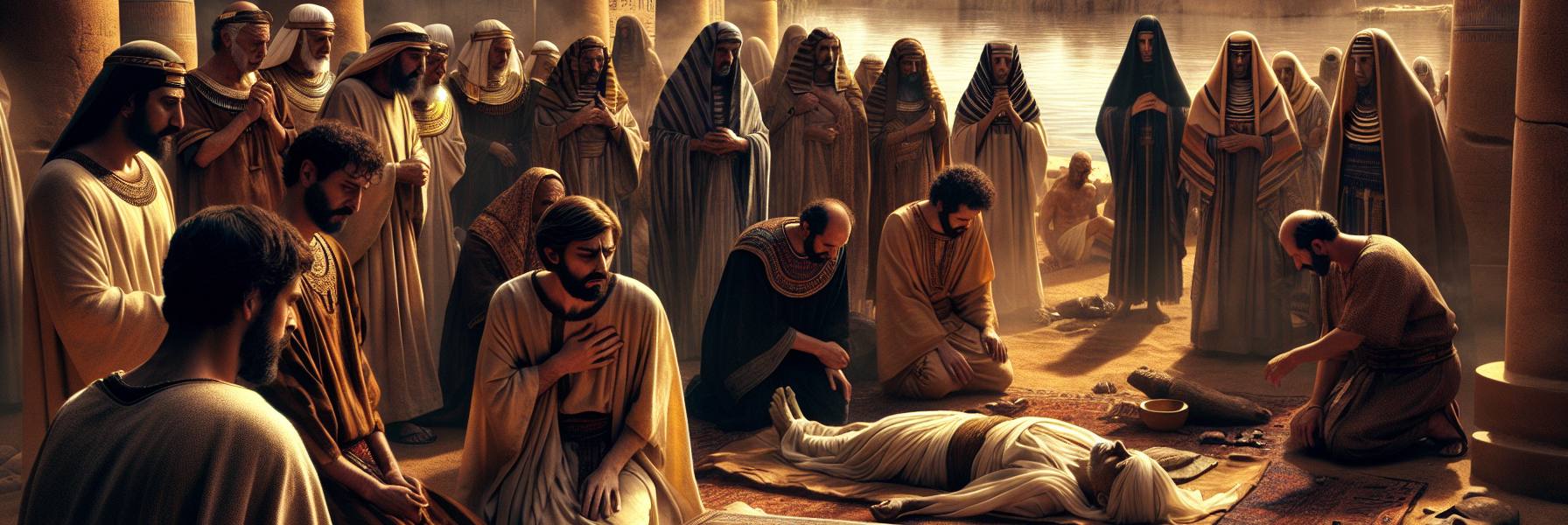

The air in the room was thick with the smell of embalming spices and grief. For forty days they had mourned him, the Egyptians whose lives he had saved, and for seventy more his own family kept to their tents by the Nile, the sound of their lamentations mingling with the slow, green flow of the river. Joseph, his face a map of dry riverbeds etched by tears, finally felt the hollow stillness that follows a great storm. His father was gone. The weight of it was a physical thing, a stone settled deep in his chest.

The brothers watched him. In the silent spaces between the formal rites, their old fear, long buried under seventeen years of gracious living, began to stir like a creature unearthed from a tomb. They huddled together in the courtyard of Joseph’s Memphis residence, the sun baking the white plaster walls.

“What if he harbors it still?” Judah muttered, his voice low. “All these years, his kindness was for our father’s sake. Now that Jacob is laid to rest…”

“He will remember,” Reuben said heavily, his big hands clenched. “He will remember the pit. And we will be servants, or worse.”

A decision was reached in that anxious council. They would not wait for his judgment. They would petition, using the words of the dead as their shield. They crafted a message, a delicate fabrication woven with threads of truth. “*Before he died, your father gave this command,*” they would say. They sent the word to Joseph, asking for an audience.

When they were brought before him, they did not merely bow—they threw themselves on the ground at his feet. The sight was a strange echo of his boyhood dreams, but now it brought no thrill, only a weary ache. “We are your slaves,” they said, their voices muffled against the cool stone floor.

Joseph sighed, a sound that seemed to come from the depths of the stone in his chest. “Leave us,” he said to his attendants. The shuffle of their retreating sandals faded into silence. He looked at the prone forms of his brothers, these men who were now grey-bearded and worn, and he saw, for a fleeting moment, the fierce young faces that had once looked down into a dry cistern.

“Come closer,” he said, his voice softer than they expected.

They rose slowly, dusting their knees, unable to meet his eye. It was then that one of them, perhaps Simeon, found the rehearsed words. “Your father commanded us before he died, saying, ‘Thus you shall say to Joseph: Please forgive the transgression of your brothers and their sin, for they did evil to you.’ And now, please forgive the servants of the God of your father.”

The plea hung in the air. Joseph turned and walked to a window, looking out over the ordered gardens of Egypt. He could almost hear Jacob’s voice, not in this stiff, diplomatic message, but in the old man’s final, rasping breaths in Goshen, his gnarled hand clinging to Joseph’s. The request was a fiction, he knew. But the fear behind it was devastatingly real.

When he turned back, his eyes were wet. His brothers flinched at the sight, bracing for a prince’s cold fury. But what broke from Joseph was not a decree, but a ragged question of his own.

“Am I in the place of God?”

The words stunned them. He took a step forward, his composure crumbling not into anger, but into a profound and painful clarity. “You intended evil against me,” he said, and each word was precise, an acknowledgment of the old, sharp truth. “You sold me. You meant it for harm. I do not pretend otherwise. I remember the darkness. I remember the taste of fear.”

He paused, swallowing hard. “But God,” he said, and the name was not a religious formula but a weighty, lived reality, “God intended it for good. He meant it to bring about what is now the case: the preservation of many lives. To save a remnant in the earth. To keep us alive, as we are today.”

He looked at each of them—Reuben, Judah, Benjamin, all of them. “So now, do not be afraid. I myself will provide for you and your little ones.”

And then he did something he had not done since they first stood before him as Egypt’s vizier: he spoke to them as a brother. He comforted them. He spoke to their hearts, repeating the promise, until the terror in their eyes began to thaw, replaced first by disbelief, then by a dawning, fragile hope.

***

The journey to Canaan was a somber, grand procession. Chariots and horsemen, a whole cohort of Pharaoh’s guard, the elders of Egypt, and all of Joseph’s household wound their way east, a cloud of dust marking their passage. They came to the threshing floor of Atad, beyond the Jordan, and there they held a great and grievous lamentation for seven days. The Canaanites, watching from the hills, named the place *Abel-mizraim*, the mourning of Egypt. It was a foreign, solemn witness to the passing of a stranger who had become their father.

They buried him as he had asked, in the cave of the field at Machpelah, beside Leah. The smell of the promise-land—dry grass, earth, and olive trees—was different from the damp, rich scent of the Nile delta. The act felt final, like the closing of a great book. Then they all returned to Egypt, to Goshen, the brothers, their families, the servants. The great caravan turned back from the land of the promise, to the land of their provision.

Life resumed its pattern. The seasons of planting and harvest came and went in the rich black soil of the Delta. Joseph lived to see Ephraim’s children to the third generation, and the children of Machir, the son of Manasseh, were born on his knees. He would hold them, these little ones who knew nothing of pits or prisons, and feel the deep, strange turn of the circle.

When his own time drew near, he called for his brothers, for all his father’s house. His room was dim, the light filtering through the linen at the window. His voice was thin but clear.

“I am about to die,” he said. “But God will surely visit you. He will bring you up out of this land to the land that he swore to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob.”

He made them swear an oath, a solemn, binding thing. “When God visits you, you shall carry my bones up from here.” He did not say “if.” He said “when.” It was the unwavering thread of his life, the interpretation of dreams and famine and betrayal: God would visit.

They swore to him. And soon after, they embalmed him and laid him in a coffin in Egypt. Not in a tomb, but in a coffin. A box made for traveling. It remained there, in a room in Goshen, a silent, wooden promise. A piece of the promise-land waiting in the heart of Egypt. The brothers would pass the room and remember. They would tell their children, who would tell theirs. They lived, and were fruitful, and multiplied greatly. But in the corner of their collective memory, in the back of their minds, was the coffin, and the oath, and the patient, unshakeable certainty of a visitation yet to come.