The memory comes to me not as a vision, but as a weight. It sits in the gut, this knowledge, a cold stone of having witnessed. I was on the Patmos shore, but not the one of gulls and fishermen. This was a different strand, a place of black sand and a sea like smoked glass, still and ominous.

The first thing was not a thing at all, but a vacancy. The sky, usually thick with the presence of the Throne, felt thin. A silence deeper than quiet settled. Then the glassy sea stirred, not with waves, but from beneath, as something immense breached its foundations.

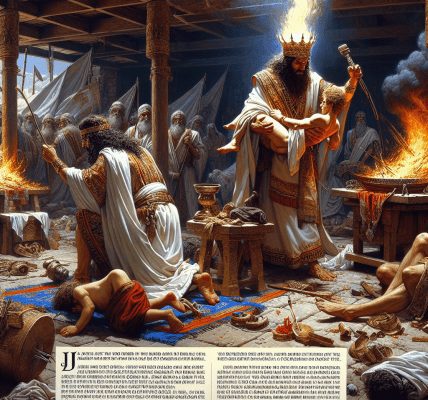

It hauled itself onto the black sand, a beast of impossible lineage. Not a lion, though it had the ragged mane of one, matted with brine and something darker. Not a bear, though its flanks had that terrible, sloping power. Not a leopard, though its hide, where it wasn’t scarred, held the ghost of that sinuous speed. It was a composite of every predatory throne that had ever crushed the earth. Its seven heads were not regal, but wounded, each bearing a name of blasphemy, slurred into its flesh like a brand. Ten horns, crowned not with gold, but with crude, thorny diadems. Its mouth was a cave, and from it came not a roar, but speech—great, swelling words of defiance, jokes told at the expense of the Holy. The dragon, the old serpent, stood at the water’s edge and gave it his own grim authority, his ruinous strength. One of its heads seemed freshly killed, a gaping, necrotic wound that made the others writhe in fury. And then the wound closed. The flesh knitted before my eyes, a parody of resurrection, and the whole world, it seemed to me in that moment, caught its breath and then sighed in a terrible, willing admiration.

A voice, not my own, spoke in my spirit: *See the parodist. See the mocker of the Lamb slain. His victory is a death, and his resurrection a lie.*

The beast spoke. It didn’t command armies; it authored narratives. For forty-two months it spun a tale where darkness was light, where the bound were free, where its name was the only name worth speaking. It blasphemed the Tabernacle itself, the true dwelling, and those who have their home there. And the earth-dwellers—those who find their all in dust—they listened. They marveled. “Who is like the Beast?” they chanted, their voices a rising tide. “Who can make war against him?” They did not ask if they should.

But the horror had a second act. From the tear in reality, from the very crust of the earth, a second beast emerged. This one was different. It wore the guise of a lamb, soft-wooled, gentle-eyed. But its voice was the dragon’s voice, a grating, metallic dissonance. It served the first beast, a vizier to the tyrant, and its power was not in claws but in persuasion. It made the earth and its inhabitants worship the first beast, the one whose mortal wound was so theatrically healed.

This second one performed signs. It called fire down from heaven in the sight of men, a cheap imitation of Elijah. It was a master of spectacle, a director of dreadful wonders. And it spoke. Oh, how it spoke. It gave the first beast a voice, an image, a presence in every square and every home. It commanded an image to be made for the first beast, an idol not of stone but of spirit and coercion. And it was given breath—not life, but a semblance of it—so the image could speak. And it could enforce. It could decree that those who would not bow to the image of the beast should be killed.

Here was the true, grinding mechanism of the lie. It wasn’t just about awe; it was about identity. It marked them. Not on the hand at first, not on the forehead. It marked them in the marketplace, in the transaction, in the simple act of buying bread.

“No one may buy or sell,” the lamb-voiced beast declared, its tone almost sorrowful, reasonable, “save he that has the mark, the name of the beast, or the number of its name.”

I saw a man, a potter, his hands grey with clay. He stood before a baker’s stall. The baker, a friend for years, would not meet his eye. “The mark, Reuben,” the baker whispered, staring at his own feet. “I have a family.” The potter’s empty hands closed into fists. That was the mark, in that moment: the empty hands.

The voice in my spirit returned, weary now, implacable. *Here is wisdom. Let him that has understanding count.*

And it was given to me, not as a flash of light, but as a slow, dawning sickness. The number of the beast. It was a human number. The culmination of all human striving without God, the pinnacle of self-made glory, the ultimate system. It was the number of a name. I saw it not in digits, but in essence: six hundred, sixty-six.

Not a triple six of evil magic, but a falling short. A relentless, repeating almost. Six, one short of seven, the number of divine completion. Again. And again. Perpetual incompleteness masquerading as sufficiency. The final, total claim of the creature to be its own creator, its own savior, its own god. A closed system. A perfect, terrible logic.

The vision faded from my eyes, leaving the ordinary sun of Patmos blinding. But the stone of memory remained. The sea now was blue, the gulls cried, the fishermen mended their nets. But I knew. The drama would not always be on a shore of black sand. It would be in the marketplace. In the vote. In the chant. In the reasonable, lamb-voiced argument that makes the unthinkable routine. It would be in the slow, willing surrender of a hand, or a forehead, or a soul, for the sake of buying bread.

And the call, for those with ears, was not to fight the beast with its own weapons. It was a call to a different patience. A different faithfulness. To have a name written in a different Book, known by a different Shepherd. Even if it means empty hands. Even if it means everything.