The heat that summer was a thick, woolen blanket over Jerusalem. It lay heavy on the king’s shoulders, even in the shaded stone rooms of his palace. David, his beard now more silver than russet, felt the weight of years and peace. The wars were quiet. The kingdom, from Dan to Beersheba, was secure. And in that stillness, a quiet, gnawing thought began to pulse—a thought that did not feel like his own, yet one he welcomed. It spoke of strength, of accomplishment, of the magnificent engine of war he had built.

He sent for Joab, the commander whose face was a map of old battles. “Go,” David said, his voice echoing slightly in the chamber. “Take the captains of the army. Number Israel. From Beersheba’s dry wells to Dan’s misty heights. I would know the strength of my hand.”

Joab stood very still. The king saw not defiance, but a deep, weary confusion in the man’s eyes. “My lord,” Joab’s voice was gravel, “may the Lord your God add to the people a hundred times as many as they are. Why does my lord the king delight in this thing? Why should he bring guilt upon Israel?”

But the word had taken root in David like a stubborn weed. His pride, a subtle and patient foe, had found its moment. The quiet statistics of peace felt like an affront to the glorious, noisy tally of war. He overruled Joab’s protest, and the command, sharp as a blade, went out.

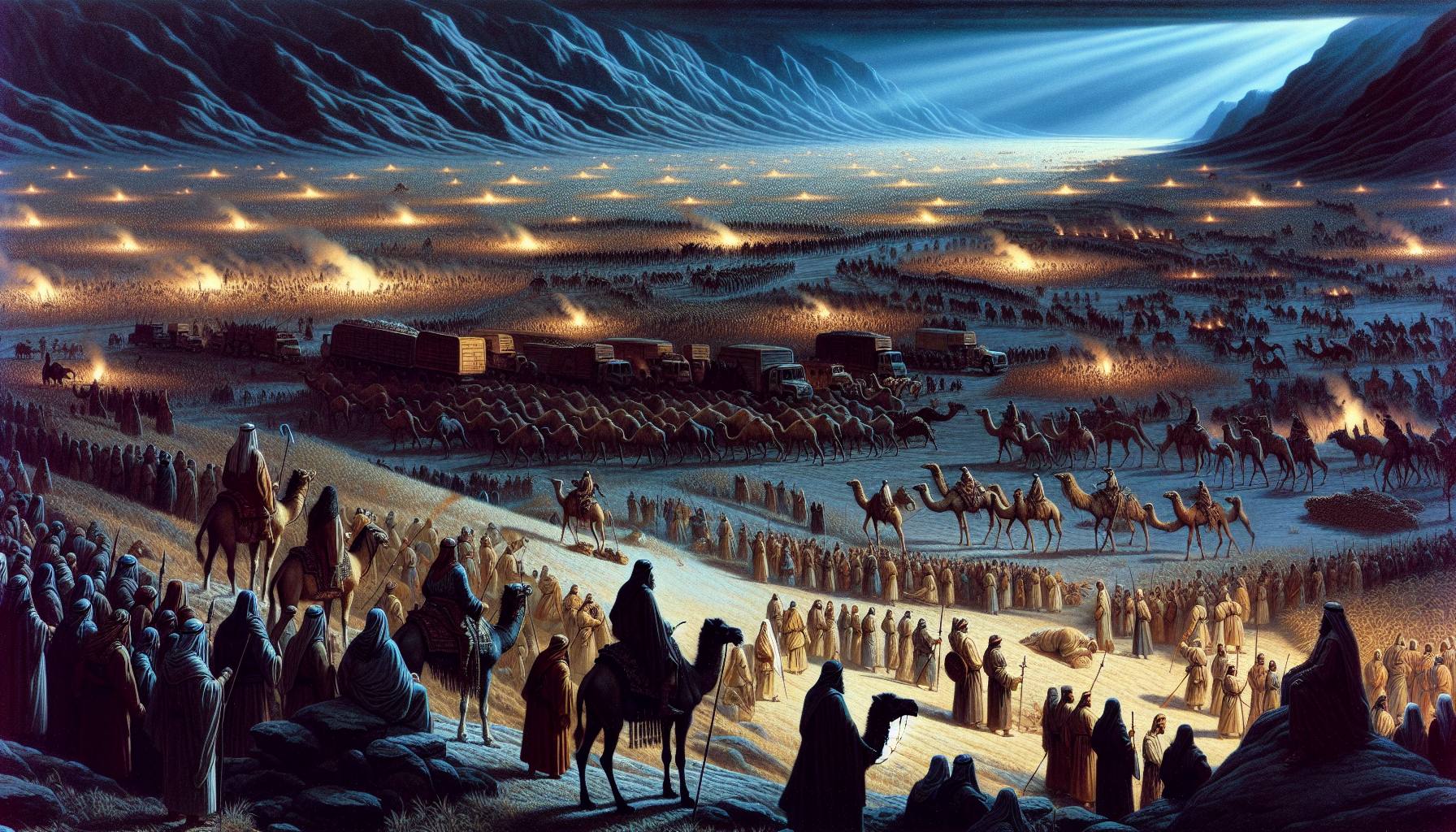

For months, the captains traveled. They crossed muddy fords and dusty trade roads, not to muster for battle, but to count. They counted men who drew water from cisterns, who tended vines on terraced hills, who argued in gateways over the price of grain. They counted the sinew and breath of a nation at rest, and the task felt wrong in their hands. Joab, ever pragmatic, did the work, but his final report was delivered with a stiff back and averted eyes. He omitted Levi and Benjamin, a small, silent rebellion. The number was still vast, a testament to power: one million one hundred thousand swordsmen.

And the moment the number left Joab’s lips, David’s heart seized. It wasn’t triumph that flooded him, but a cold, sinking dread. The air in the room grew thin. The impressive figure echoed emptily. He had not numbered the Lord’s people; he had numbered his own possession. He had sought a measure of his own glory, and in finding it, found only a vast, hollow silence where God’s favor had been.

“I have sinned greatly,” he rasped to the empty air, then to his counselors. “I have done very foolishly. Take this iniquity away from your servant.”

That night, the prophet Gad came to him. Gad’s face was lined with a sorrow that seemed older than the hills. He did not mince words. The voice of the Lord had given a choice, a terrible trilemma born of justice, yet laced with a sliver of mercy—the mercy of choice itself.

“Three things I offer you,” Gad said, his tone flat, the bearer of dreadful news. “Three years of famine. Three months of devastation before your foes. Or three days of the sword of the Lord, a plague in the land.”

David’s choice was the agony of a shepherd-king. Famine was slow, cruel, indiscriminate. The sword of enemies was a shame that would touch his own honor. But the pestilence… that was the direct hand of the God he had grieved. “I am in great distress,” he whispered, his face in his hands. “Let me fall into the hand of the Lord, for his mercy is very great; but let me not fall into the hand of man.”

It began at dawn. A whisper of sickness, then a wail from a house in the northern quarter. Then another. By midday, a terrible stillness was spreading from town to village. Not the stillness of peace, but of arrest. People were found slumped in fields, cold at their market stalls. There was no battle cry, no invading army, only an invisible, wasting angel whose shadow was death. From the wilderness of Dan to the gates of Jerusalem itself, the plague marched. Seventy thousand men fell. The air grew thick with the smell of smoke from funeral pyres.

In Jerusalem, David watched in an agony that mirrored the land’s. He saw the destroying angel, a spectral horror suspended between heaven and earth, his hand stretched out over the city, hovering specifically over the threshing floor of Ornan the Jebusite. The sight broke him utterly. He tore his royal robes and put on the rough, penitential sackcloth of common mourners. He went out, his officials trailing him in terrified silence, and climbed the terraced path to the high place of Ornan.

Ornan was threshing wheat, the rhythmic *whoosh-thud* of the flail a sound of mundane life in the midst of cosmic judgment. He turned and saw the king—not in purple, but in sackcloth—and his four sons with him, hiding in fear. Ornan ceased his work and bowed, his face to the earth.

“Sell me the site of this threshing floor,” David said, his voice raw. “That I may build an altar to the Lord, that the plague may be averted from the people. Sell it to me for full price.”

Ornan, a practical man, saw more than real estate. He saw a broken king and a desperate chance for salvation. “Take it, my lord the king!” he urged. “Take it, and do what seems good to you. See, I give the oxen for burnt offerings and the threshing sledges for wood and the wheat for a grain offering. I give it all.”

But David, his lesson seared into his soul, refused. “No. I will buy it for the full price. I will not offer to the Lord my God that which costs me nothing.” The transaction was solemn: six hundred shekels of gold by weight, a king’s ransom for a patch of rocky earth.

There, on that purchased ground, David built an altar. He called upon the Lord, and as he offered the burnt offerings and peace offerings, a strange, focused fire fell from heaven. It consumed the offerings upon the altar, a clear, terrible, and gracious sign. And David, watching the holy fire, knew it was the answer. He spoke the command to the unseen presence: “Put your sword back into its sheath.”

The angel sheathed his sword. The plague ceased. The dread lifted like a fever breaking.

David did not leave that place. He continued to sacrifice there, for he was afraid to go to the high place at Gibeon, the old tabernacle. This new place, bought with repentance and paid for in full, had become holy ground. The terror of the Lord had met the magnitude of his mercy. The story would later be told in whispers: how the king’s pride had brought a curse, and how his repentant bargain on a Jebusite’s hill had, in time, become the chosen site. The place where an altar of desperation stood would one day hold the Temple of Solomon, the dwelling place of God among men. It all began with a count that should never have been taken, and a cost a king finally learned he had to pay.