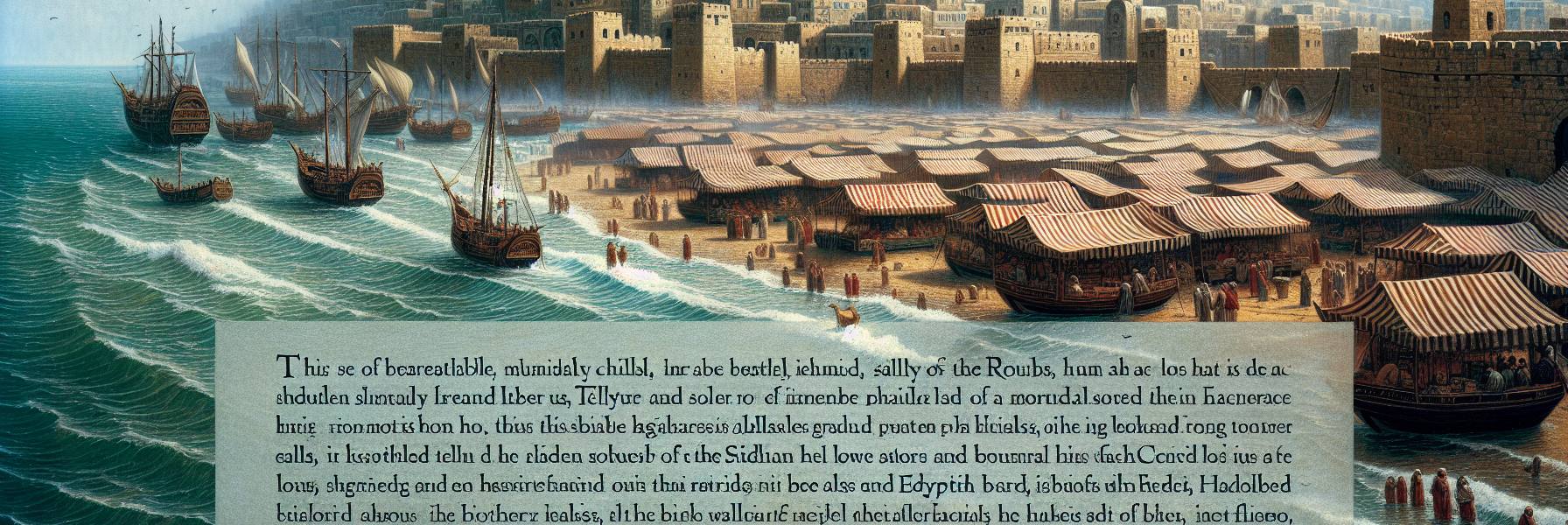

The salt air was thick that morning, a tangible dampness that clung to beards and cloaks and the striped awnings of the market stalls. Elior ben-Malkiya felt it in his bones, a deep, unseasonable chill as he walked the great causeway connecting the island city to the mainland. Tyre, the Rock, stood unassailable, her twin harbours—the Sidonian to the north, the Egyptian to the south—churning with the comings and goings of cedar ships and galleys. From the mainland quarter of Ushu, he looked back at the towering walls, their stones stained dark by centuries of sea spray and smoke, and felt not pride, but a hollow dread.

The news from Jerusalem had finally arrived, not by official courier, but in the hushed, excited whispers of Phoenician merchants whose eyes glittered with opportunity. The Babylonians had broken through. The walls were breached. The Temple, they said, was plundered. Judah had fallen.

And Tyre rejoiced.

Well, not all of Tyre. Elior, a dealer in fine oils and a son of Judah by his mother, heard the rejoicing from the lips of others. He stood now at the stall of Habaz, a ship-owner from Arvad. “A great day!” Habaz boomed, slapping a ledger. “The gateway is cleared! Jerusalem sat astride the inland routes, demanding her share, slowing the caravans. Now? Now the wealth of Aram and the Negev flows straight to our docks. Nebuchadnezzar has done us a favour, he has. He’s a businessman, that king. He’ll want his share too, of course, but the flow… the flow will be ours to direct.”

Elior nodded mechanically, his gaze drifting past Habaz to the teeming wharf. He saw the gates not as commerce, but as a breached doorway in the house of his mother’s God. A verse, learned at his mother’s knee in this very city of strangers, echoed with a new and terrible clarity in his mind: *Because you have said, ‘Aha! Against the gates of the peoples she is broken; she has turned to me; I shall be filled, now that she is laid waste…’*

The words fit the smugness around him like a key in a lock. Tyre saw Judah’s catastrophe as a market correction. The city, this glittering, arrogant jewel set in the sea, believed itself the inevitable beneficiary of every earthly calamity. It stood apart, inviolate, its wealth drawn from the misfortunes of the mainland. It saw God’s judgment on Jerusalem as its own prosperity.

Days bled into weeks. The official word came: Jerusalem was a ruin. The exiles were trudging north towards Babylon. And in Tyre, the feast of Melqart, the city god, was celebrated with unprecedented fervour. Drums thumped a relentless rhythm from the temple precincts atop the island’s high rock. The smell of roasting meat and cheap incense from the public sacrifices wafted across the strait to Ushu. Elior could not sleep.

One evening, the dread coalesced into a vision so sharp it stole his breath. It was not a dream; he was awake, staring at the mud-brick wall of his rented room. But he saw the sea. He saw Tyre. And a voice, not with sound but with the force of a thought implanted, spoke.

*Therefore, thus says the Lord GOD: Behold, I am against you, O Tyre, and will bring up many nations against you, as the sea brings up its waves.*

The image shifted. He saw not the elegant triremes of Tyre, but a multitude of crude, strong vessels—ships of Babylon, of Persia, of islands whose names he did not know. They came not for trade, but in a line of war, like waves in a storm-driven tide, one after the other, relentless.

*They shall destroy the walls of Tyre and break down her towers.*

He saw the great walls, the pride of a thousand years. He saw the crash of siege engines, not against gates, but against the very island’s foot. Stones, each one worth a fortune in labour, tumbled into the strait. The meticulous masonry of Hiram’s builders was reduced to scree.

*And I will scrape her soil from her and make her a bare rock.*

This was the most chilling detail. It was not just conquest. It was erasure. He saw dredges, saw gangs of slaves with picks and baskets, not building but un-building. They were taking the very island apart. The splendid city, its warehouses crammed with purple dye and silver, its temples adorned with gold looted from a hundred coasts, would be picked clean. Its soil, the ground of its being, would be cast into the water.

*She shall be in the midst of the sea a place for the spreading of nets.*

The vision cleared, leaving only the after-image. The drumming from the island had stopped. In the silence, Elior understood. The judgment was not merely military; it was a profound reversal of identity. The bustling port, the nexus of the world’s wealth, would become empty. Silent. Useful only to fishermen mending their nets, a flat, barren rock where gulls would nest and winds would howl unimpeded. The memory of its splendour would be a ghost story told by old men on distant shores.

Years passed. The Babylonian army, flush with victory, did indeed come. Nebuchadnezzar’s forces laid siege to the mainland town for thirteen years. They took Ushu. They broke its walls. But the island city, supplied by its fleet, held out behind its walls. The siege ended in a negotiated peace. Tyre, it seemed, had survived. Men like Habaz laughed again, though less loudly. “The sea is our wall,” they said. “No king of the mainland can conquer the sea.”

Elior, now an old man, did not laugh. He remembered the vision of the many nations, the many waves. Nebuchadnezzar was but the first wave, breaking on the rock. The dread remained.

More decades flowed. New powers rose. And finally, two and a half centuries after Elior’s vision, a new king came, one possessed of a terrible, singular will. Alexander of Macedon, facing the defiant island city, did not build ships. He read the geography as a problem in engineering. He used the rubble of the ancient mainland city, the dust of Ushu, and he built a *mole*—a great causeway of stone and dirt—straight out through the strait towards the island walls.

Elior’s grandson’s grandson walked on a different shore, watching the impossible happen. He saw the island become a peninsula. He saw Alexander’s towers roll forward on the ever-advancing land bridge. He saw the final assault. And when it was over, he saw the conqueror, in a fit of rage at the city’s resistance and as a lesson to the world, order a thorough destruction.

They did not just break the walls. They scraped the very soil. They threw the timber and the marble and the precious rubble of the palaces into the sea to widen the causeway. They left the Rock bare.

Centuries later, a Galilean fisherman named Peter, passing along the coast, might have seen a few poor huts amid the ruins. But mostly, he would have seen a wide, flat shelf of rock jutting into the water, where other fishermen—men with names like Andrew and James and John—were indeed spreading their nets to dry in the sun, just as the old, terrible, and utterly precise words had foretold. The sea, which had been Tyre’s fortress, was now its only memorial, whispering over the smooth stones where no city would ever stand again.