**The Final Plague: The Death of the Firstborn**

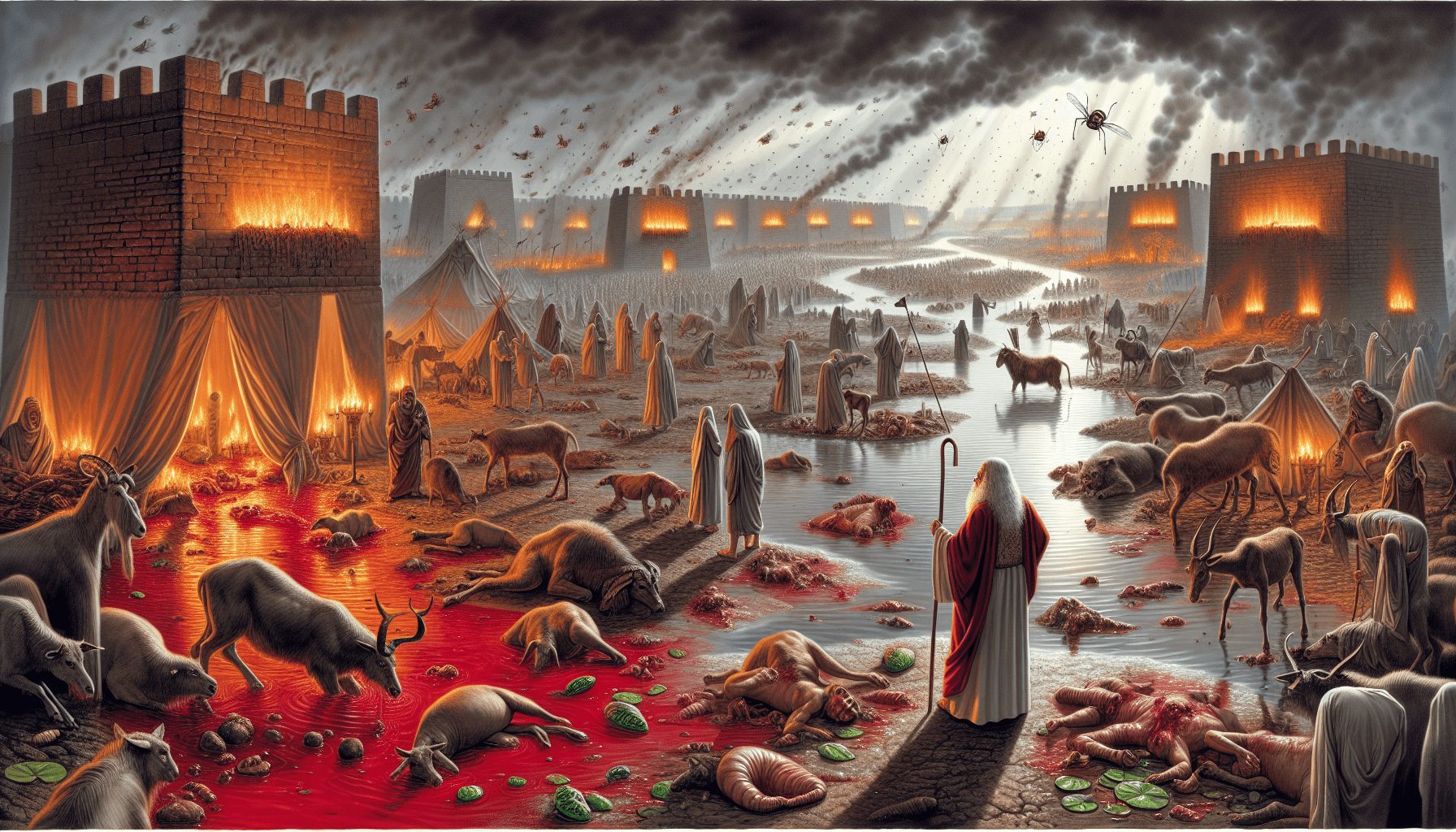

The air in Egypt was heavy with tension, like the oppressive stillness before a storm. The land, once proud and unyielding, now bore the scars of nine devastating plagues. The Nile had turned to blood, frogs had overrun the land, gnats and flies had tormented both man and beast, livestock had perished, boils had afflicted the people, hail had shattered crops, locusts had devoured what remained, and darkness had shrouded the land in an impenetrable gloom. Yet, Pharaoh’s heart remained hardened, and he refused to let the Israelites go.

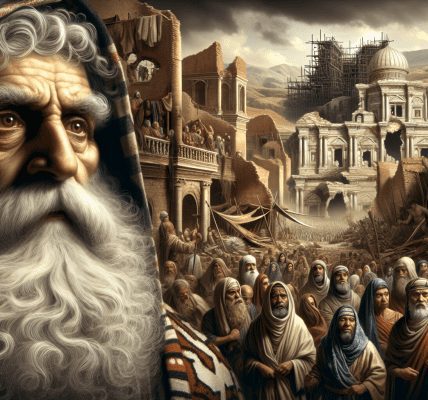

Moses stood before Pharaoh in the royal court, his weathered face set with determination. The flickering light of the oil lamps cast long shadows on the walls, and the air was thick with the scent of incense and the unspoken dread of what was to come. Pharaoh, seated on his golden throne, glared at Moses with a mixture of anger and defiance. His advisors stood nearby, their faces pale and drawn, for they had begun to fear the power of the God of the Hebrews.

“Thus says the Lord,” Moses declared, his voice steady and resonant, “About midnight I will go out into the midst of Egypt, and every firstborn in the land of Egypt shall die, from the firstborn of Pharaoh who sits on his throne, even to the firstborn of the female servant who is behind the handmill, and all the firstborn of the cattle. There shall be a great cry throughout all the land of Egypt, such as there has never been, nor ever will be again.”

The words hung in the air like a death sentence. Pharaoh’s face darkened, but Moses continued, unwavering. “But not a dog shall growl against any of the people of Israel, either man or beast, that you may know that the Lord makes a distinction between Egypt and Israel. And all these your servants shall come down to me and bow down to me, saying, ‘Get out, you and all the people who follow you.’ After that, I will go out.”

With that, Moses turned and left the palace, his staff in hand, the weight of the Lord’s command upon him. The streets of Egypt were eerily quiet, as though the land itself was holding its breath. The people of Israel, however, were abuzz with activity. Moses had instructed them to prepare for their departure, for the time of their deliverance was at hand.

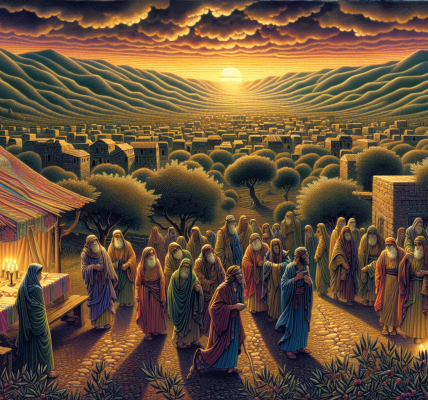

That evening, as the sun dipped below the horizon, painting the sky in hues of crimson and gold, the Israelites gathered in their homes. They had been given specific instructions by the Lord through Moses. Each family was to take a lamb, a male without blemish, and slaughter it at twilight. They were to take some of the blood and put it on the two doorposts and the lintel of their houses. The lamb was to be roasted and eaten with unleavened bread and bitter herbs, their belts fastened, their sandals on their feet, and their staffs in their hands. They were to eat in haste, for it was the Lord’s Passover.

The Israelites obeyed without question. The sound of lambs being slaughtered echoed through the night, and the smell of roasting meat filled the air. The blood on the doorposts gleamed in the flickering light of the oil lamps, a sign of obedience and faith. Inside their homes, families gathered together, their hearts filled with both fear and hope. The children, sensing the gravity of the moment, clung to their parents, their eyes wide with wonder.

As midnight approached, a deep silence fell over the land of Egypt. The stars above seemed to dim, and the moon hid behind a veil of clouds. Then, suddenly, a piercing cry shattered the stillness. It began in the palace of Pharaoh and spread like wildfire through every home in Egypt. The Lord had passed through the land, striking down every firstborn, from the highest to the lowest. The wails of grief and despair rose into the night, a cacophony of anguish that would be remembered for generations.

In the homes of the Israelites, however, there was only silence. The blood on their doorposts had marked them as the Lord’s people, and the destroyer had passed over them. Not a single Israelite firstborn was lost. The distinction between Egypt and Israel was clear: the Lord had shown His power and His mercy.

Pharaoh, awakened by the cries of his people, rushed to the chamber of his firstborn son. The boy lay lifeless in his bed, his face pale and still. Pharaoh’s heart, once hardened like stone, now shattered into a thousand pieces. He fell to his knees, his cries joining those of his people. In that moment, he knew that he could no longer resist the will of the Lord.

Before the first light of dawn, Pharaoh summoned Moses and Aaron. His face was ashen, his eyes hollow with grief. “Get out,” he said, his voice trembling. “Take your people and go. Serve the Lord as you have said. Take your flocks and your herds, and be gone. And bless me also.”

The Israelites, already prepared for their journey, gathered their belongings and left Egypt in haste. They carried with them the spoils of Egypt, gold and silver and clothing, given to them by the Egyptians who now feared the God of the Hebrews. As they marched out of the land of their bondage, the sun rose over the horizon, casting its golden light on the path before them. They were free at last, their deliverance a testament to the power and faithfulness of the Lord.

And so, the final plague had accomplished what the others could not. The death of the firstborn had broken Pharaoh’s pride and opened the way for the Israelites to leave Egypt. The Lord had shown Himself to be the God of justice and mercy, the Redeemer of His people. The story of the Passover would be told for generations, a reminder of the Lord’s mighty hand and His enduring covenant with His people.