The word came to Jonah a second time. This time, he went.

His feet were heavy on the road north and east, the dust of the journey coating his sandals and the hem of his robe. It was a walking through a drained soul, every step an act of will. The memory of the deep, of the seaweed wrapping his head in the temple of the fish’s belly, was a cold stone in his gut. He could still taste the salt. So he walked, a man carrying the unshakeable burden of a grace he did not wish to extend.

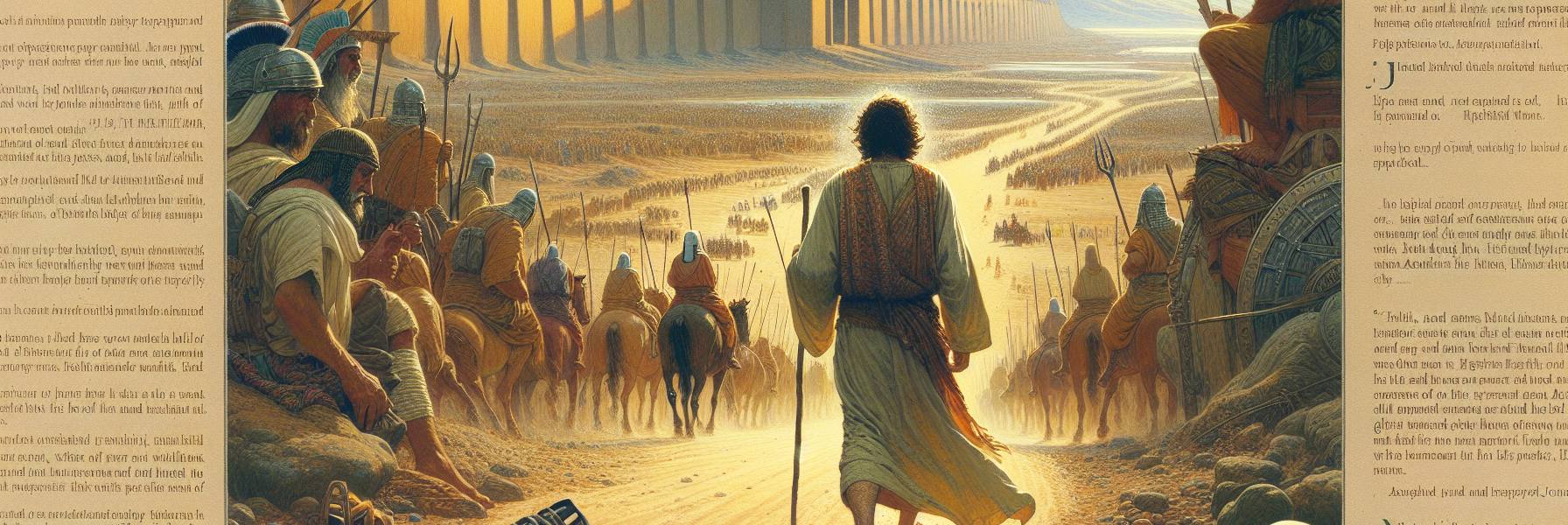

After days, the sight of Nineveh broke over the horizon. It wasn’t a city; it was a sprawl of power carved into the earth. Sunlight glinted off the helmets of guards on walls so massive they seemed to hold up the sky. The noise of it reached him first—a distant rumble of commerce, of chariots, of a hundred thousand lives lived in fierce, unknowing arrogance. The smell followed: animal fat, sewage, incense, and the dry, metallic scent of a river that had been bent to the city’s will. It was a place that declared its own permanence, a monument to human might. Jonah felt very small, a speck of dust from a backwater province standing before an engine of empire.

He entered through one of the great gates, the shadows of the fortifications cooling his sun-beaten skin. He did not look at the hawkers or the painted idols in their niches. He had one task. He walked for a full day, into the heart of the beast, letting the immensity of the place sink into his bones. *A three days’ walk across*, the word had said. He believed it.

On the second day, his voice found him. It started low, a gravelly thing torn from his throat.

“Forty days,” he called out, not to any one person, but to the walls, to the air itself. “Forty days, and Nineveh will be overthrown.”

He didn’t elaborate. He offered no poetry, no pleading, no conditions. Just the stark, declarative sentence, a hammer-blow of a truth. He moved through a market square where spices hung in colorful sacks. “Forty days!” The merchants glanced up, frowned, and went back to their weighing.

He said it in the street of the blacksmiths, the air shimmering with heat and the clang of hammers. “Overthrown!” A smith, sweat rivering through the soot on his chest, paused, his hammer halfway to an orange-hot blade. He met Jonah’s eyes for a moment, saw something there that wasn’t madness, but a terrible, sober clarity. The man’s face went slack. The hammer did not fall.

It began like that. A trickle. The words, so foreign in their absolute finality, did not argue. They simply were. A woman drawing water from a public well heard it and her clay jar slipped from her hands, shattering on the stones. She did not curse the loss. She stood, staring at the shards, then at the ragged prophet moving on. The words clung to him like a smell.

By the afternoon of that second day, a strange silence began to follow in Jonah’s wake. Not absence of sound, but a *hush*, a pocket of dread that spread out from him like a stain. Conversations stopped mid-sentence. Children were pulled indoors. The message was passed not in shouts, but in whispers. *A Hebrew prophet. Overthrown. Forty days.*

The belief did not arrive as a reasoned conclusion. It arrived as a shock to the city’s spirit, a sudden, collective intuition that the universe was not, in fact, bounded by their walls. The god of this prophet was not a god one bargained with in a temple. He was a god who spoke words that became things. And he had said, “Overthrown.”

By evening, the people—from the lowest sewer-cleaner to the wealthy merchants in their villas—were covering themselves in sackcloth, the coarse goat-hair fabric a brutal itch against their skin. They cast dust upon their heads, not as a gesture, but in a frantic, physical self-abasement. They fasted. Not from a lack of food, but from a sudden, visceral understanding that bread was irrelevant. The king’s ministers, their faces ashen, brought word to the palace.

The king himself, a man used to dictates of war and tax and stone, rose from his ivory-inlaid throne. He stripped off his royal robes, the symbols of a sovereignty that now felt like a paper crown. He too put on sackcloth, the roughness a shocking humility against his skin, and sat down in the dust of the palace courtyard. Then he issued a decree, one that echoed through the city’s canals and streets.

“By the decree of the king and his nobles: Let no man or beast, herd or flock, taste anything. Let them not feed, nor drink water. But let every person—and every animal—be covered in sackcloth, and let them cry out to the god of the Hebrews with all their strength. Let every man turn from his evil way, from the violence that is in his hands. Who knows? The god may turn and relent. He may turn from his fierce anger, so that we do not perish.”

It was the “who knows?” that defined it. This was not a transaction. It was a plea hurled into the terrifying, merciful unknown.

So Nineveh fell still. The chariot wheels stopped. The forges went cold. The markets were empty but for the drifting dust. From the highest tower to the lowest sheepfold, a city clothed in sackcloth held its breath. The only sounds were the faint, desperate cries of people—and the confused, hungry bleats of sheep and lowing of cattle, also draped in rough cloth—calling out to a god whose name they barely knew.

Jonah watched it all from a lonely height on the city’s edge. He saw the silence spread. He heard the city’s roar diminish into a unified, animal groan of repentance. And he felt no triumph. Only a cold, sinking certainty. He knew the character of the god he served. He knew what “who knows?” truly meant. The city’s hope was his own bitter disappointment. The mercy he had feared on the ship, the mercy that had pursued him into the deep, was now flowing like a river through the streets of his enemies. He had done his duty. And in doing so, he had succeeded in saving the very thing he wished to see burn.

He wrapped his own cloak around himself, a man alone in the midst of a repentant multitude, and waited for the forty days to dawn.